The CD is 30 years old today

Today’s a significant anniversary in the history of recorded music: the world's first CD players were announced in Japan on October 1st, 1982.

And despite the rearguard action fought by some record companies – and some audiophile reviewers who went into full, barricade-manning denial at the time – it’s still with us as a highly successful medium for recorded music, the antecedent of modern DVDs and Blu-rays and the precursor of today’s digital download trend.

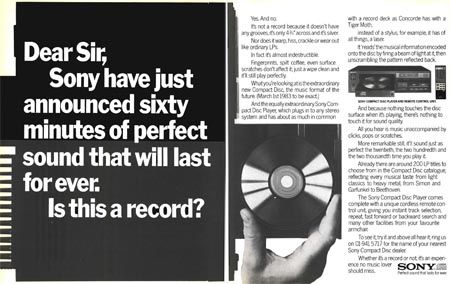

By Autumn 1982 the CD momentum had been building for a while, but it was on October 1st that Sony launched its first player, the CDP-101, along with the first album available on the new format – Billy Joel's 52nd Street.

Eight years in the making

However, the project to store music on an optical disc was founded by Philips as far back as 1974, and the suggestion that a 20cm disc be used. In turn, that was based on an even earlier Philips project, Audio Long Play, using laser technology.

By 1977 the format for players and discs was beginning to come together, with the Philips engineers taking the 'Compact Disc' name from their last success, the compact cassette, and suggesting a disc with an 11.5cm diameter - the diagonal measurement of a cassette – to give a running time of one hour.

By now, some original ideas about making the format quadrophonic rather than stereo had been dumped: to do that would have meant going for that 20cm disc, and the 'compact' idea was taking hold.

Get the What Hi-Fi? Newsletter

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

Almost a format war

Meanwhile, in what could have been the makings of a format war, Sony engineers had shown an optical audio format in September 1976, and by 1978 had a disc giving a playing time of 150 minutes using a 44.1kHz - well actually 44.056kHz - sampling rate and 16-bit resolution.

They presented this at the 1979 Audio Engineering Society convention, which was held in Belgium. And in typical format war style, a week before, Philips held an event called 'Philips Introduce Compact Disc'.

Driven by Sony exec Norio Ohga, a keen musician, friend of the conductor Herbert von Karajan and head of CBS/Sony Records by the relatively young age of 40 – he'd later go on to become Sony president, CEO and eventually succeed founder Akio Morita as chairman – Sony and Philips (thankfully) joined forces to co-develop the format.

A joint conference, with Karajan (above) taking centre stage between Joop Sinjou of Philips and Sony's Akio Morita, was held to announce the venture, and the brought together the two companies' technologies, and came up with the Red Book standard – despite the colour, the blueprint for the format – in 1980.

Why 44.1kHz?

Here comes the science bit, and for the purposes of this blog I'm going to keep it simple – hopefully!

The choice of audio format for CD was a mixture of available technology and what was possible at the time. CD needed a format capable of covering the audible frequency spectrum – 20Hz-20kHz – and that meant a sampling rate of at least twice 20kHz would be required.

Fortunately a solution was at hand, in the form of a technology used to store audio, for example for transfer between studios and so on: Sony's U-matic video tape (left).

Originally made for professional video applications, this could be used with a PCM adaptor to store six audio samples per video line – ie three samples for each stereo channel.

And given the 245 usable lines per field and just under 60 fields per second of NTSC video, and the 294 lines/60 fields of PAL video, this gave a sampling rate of 44.056 samples per second for each stereo channel on NTSC format, or 44.1kHz on PAL. Not surprisingly, given that Japan was an NTSC territory, that standard was the one the Sony engineers were working to.

Why 16-bit?

The system could store 16-bit samples, but needed error correction to do so accurately, or could store 14-bit with no correction, and for a while the Philips engineers proposed 14-bit with a 44kHz sampling rate, while the Sony team pushed for – well actually insisted on – 16-bit with either 44.056kHz or 44.1kHz sampling.

The difference? Well, the greater the number of bits, the more 'steps' can be used to describe each sample, and more steps means greater resolution.

16-bit provides 65,536 voltage values (or steps) for each sample, while 14-bit gives 16,384 – or in other words a quarter as many as 16-bit.

Going into the CD age, Philips already had a 14-bit digital to analogue converter, but the Sony engineers prevailed, and 16-bit/44.1kHz it was.

For their machines, the Philips team made the 14-bit system deliver the same quality by using four times oversampling – running the converter at four times the 44.1kHz sampling rate – and thus improving resolution while reducing noise.

And why the 12cm disc? Beethoven's 9th...?

And no doubt influenced by both the conductor and his friend Ohga, the CD format changed again, growing to 12cm. Why? Simply because Sony insisted that the running time should be sufficient to hold the whole of Beethoven's 9th Symphony.

And given that the longest-running version of the 9th in the Philips-owned Polygram catalogue – Furtwangler's 1951 Bayreuth Festival recording – was 74 minutes, that became the standard. 12cm – rather than the previous 11.5cm, designed to hold an hour of music, or the 10cm disc Sony had been proposing – was what we got.

... Or a matter of competitive advantage?

Well, that's one version of the story: the other is that Philips was already set up to press the 11.5cm discs, and so had an advantage over Sony, which didn't have a plant up and running yet. By forcing the switch to 12cm, it's claimed, Ohga was able to level the playing-field again.

Whatever the truth, surprisingly the first classical disc pressed on the new format wasn't the 9th, but a Karajan recording with the Berlin Philharmonic of Strauss's Eine Alpensinfonie. The first 'pop' disc made was Abba's The Visitors, but it was beaten onto the shelves by that Billy Joel release.

'The record player is obsolete'

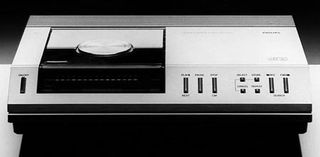

Though Sony was first to market with hardware, Philips had shown a production player in April 1982, the company's Lou Ottens, technical director of the audio division, announcing that 'From now on, the conventional record player is obsolete.' Thirty years on, 'the conventional record player' is still selling healthily!

CDs with jam on

But for many of a certain age, the first exposure to CD would have come when BBC popular science programme Tomorrow's World previewed the format. Who can forget Kieran Prendiville spreading jam on a test-pressing of a Bee Gees disc?

Here's a promotional video from Philips launched around the time of the first CDs:

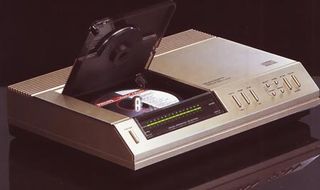

The first players were based around the drawer-loading Sony CDP-101 technology, and soon the top-loading wedge-fronted Philips CD100 (above).

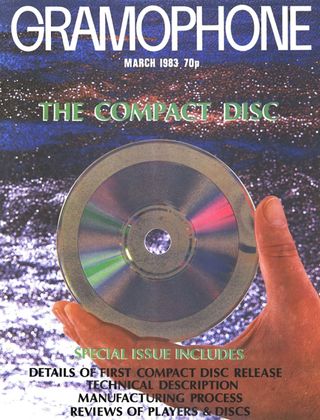

And by the time the format was officially rolled out worldwide, in March 1983, Gramophone magazine was able to publish a special section reviewing not only the discs available, but no fewer than four CD players.

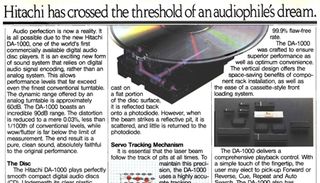

The original Philips and Sony machines were in there, along with Hitachi's DA-1000, in which the disc was clamped vertically in the manner of a cassette player, and the drawer-loading Marantz CD-73, the company's follow-up to the Philips CD100-derived CD-63.

The CD-73 had a clear panel in the top-plate, through which the green-illuminated disc could be seen spinning.

Hitachi's advertising for the DA-1000 (above), while Comet announces the Marantz CD 73, complete with its top-loading mechanism turned into a drawer-loader

The price for these players? From £450 for the Philips to £549 for the Sony, with the Marantz and Hitachi both around the £500 mark. And it's worth bearing in mind how expensive those players were: £500 in 1983 was the equivalent of around £1400 today.

The best thing since Harry Lauder

The Gramophone recording reviewers gave their opinions of their first encounters with CD, William A Chislett saying that the arrival of CD made previous experiences – including first hearing a recording of Harry Lauder singing Roaming in the gloaming when it was released in 1905! – pale into insignificance.

Lionel Salter commented that 'The pure silence against which the music can unfold is itself startling', while Edward Greenfield noted that, aside from the trickiness of fast-fowarding to find a desired passage of the music, and the need for index points within long pieces – remember them? - , CD brought 'a sense of presence comparable with that of quadrophonic at its best'. He looked forward to one day having a CD system in his car.

'The silence is deafening'

Robert Layton, meanwhile, said of the lack of background noise that 'the silence is positively deafening', and while other critics mentioned the focus the new format could throw on any failings in production or recording, Layton concluded 'I am sure there is no turning back'.

In the audio press, the arrival of CD met a mixed reception.

What Hi-Fi? (as it was then) kept its readers abreast of developments as the launch of CD approached and then as more players began to appear.

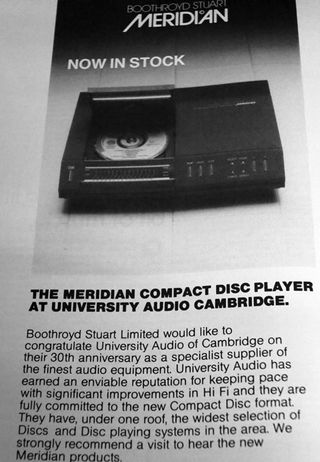

The magazine brought us news of the first all-in-one CD-playing system from Hitachi, the move of companies such as Meridian (below) into the format, and the eventual arrival of the in-car player from companies such as Sony, Philips and Pioneer.

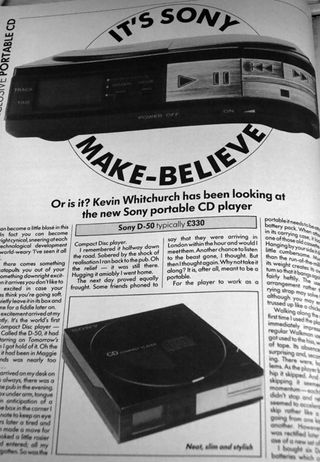

And by the end of 1984, What Hi-Fi?'s Kevin Whitchurch was getting terribly excited about the arrival of the first Sony portable player, the D50, taking the new machine home with him to try – and accidentally leaving it in a pub on the way! Those were the days…

By then WHF? also had a monthly CD review section, kicking off in August 1984 with a review of Yes’s 90125, and the view that the CD sounded a bit bright and sibilant beside the LP, a common criticism among the audiophile press at the time.

But things went further: Even as CD was launching, WHF? ran a story showing how the LP was preparing to fight back against the newcomer with the likes of Direct Metal Mastered pressings, while those magazines catering for the more 'serious' audiophile seemed decidedly detached from the whole CD thing.

Review CD players? Never! I quit!

For many years the 'vinyl is best' mantra was preached. Let's face it, in some quarters it still is, despite three decades in which the CD player has been refined and developed.

In fact, I gather from a friend working on one of Haymarket’s hi-fi magazines at the time that the resistance to CD was not only deep, but determined. Indeed, such was the intensity of the negative feeling that one staff member actually resigned rather than bow to the pressure to review CD players!

Not all audiophiles dreamed of silver discs...

However, despite the best efforts of the resistance, CD caught on pretty rapidly, although some companies held firm for as long as they could, in the belief that CD performance couldn't match what was available from vinyl. In contrast with early adopters such as Mission and Meridian, Naim didn't make a CD player until 1991, when it introduced the CDS (below), and Linn held out until 1993, finally launching the Karik that year.

Since the arrival of the CD, which all along had promised the potential for extra content such as lyrics or even pictures, we've also had various spin-offs from the original standard, designed to add functionality.

There was the Video CD, launched as a more durable alternative to the prerecorded video cassette and still popular in some markets, and CDi (below), an interactive system launched by Philips to deliver both games and movies through modified players but overtaken by the arrival of DVD, which of course also uses that 12cm disc format.

We've also had CD recorders for audio, much loved in the hi-fi community as a means of making sampler discs to carry around for demonstrations or testing, but these days all but displaced by computer storage, USB sticks and hard drives, and iPods and the like, while just about every computer still has a CD/DVD rewriter built-in.

But coming back to CD players – many of which now use just such a CD/DVD combination drive, simply because such hardware is now more available than dedicated CD-only mechanisms –, I started to wonder how far we've come since 1982?

Buying early CD players

As a relatively early adopter of CD – my first player came with a copy of the then-newly-released Brothers in Arms, which went on to give Dire Straits a place in the record books as the first million-selling CD artist – I was interested to find out, so started hunting for an early machine.

No joy on the really early stuff: the first Philips top-loaders, and derivatives such as the original Marantz CD63 (above) are now sought-after collectibles, not least among mainland European retro-audio enthusiasts, and the best I could find was around €1500 for an original model in working condition.

However, while hunting around on the internet I found hi-fi recycling specialists Green Home Electronics, and a Philips CD160 (left) in full working nick on sale for the princely sum of £19.99.

OK, not the first, but still an early player, released in around 1986, and one of the first truly affordable players Philips made in an attempt to stave off the inrush of aggressively-priced machines from points further East.

Selling for £230, it was also designed to pull more wavering consumers into CD, and it worked: this was the first CD player I bought, and now I was going back to have another listen.

Having explained to Green Home's Dave Powell why I was after the player – didn't want the word to go out that I'd fallen on hard times, after all! – he had a rummage in his store-room, which is being turned out prior to the company relocating from Berkshire to Lincolnshire, and came up with two earlier machines.

When I arrived to pick up the CD160, there was also the machine it replaced, a CD150, and a CD104, dating from 1984 and the first of the company's drawer-loaders. Amazingly the latter was boxed in slightly tatty original cardboard and came complete with its original manual.

Oh, and this was also the winner of CD player group test in the October 1984 issue of What Hi-Fi?, going on to be our CD player of the Year 1985, announced in the November 1984 magazine (below).

The earlier players were in various states of disrepair – the display was temperamental on the CD150, and the CD104 needed to be picked up and given a sharp tilt forward to coax the loader open, belying the ‘Motor Powered Loading’ script on the front of the drawer. However, both played discs fine, so having been offered all three for £30, it seemed churlish not had over the crisp folding, and load them all in the boot of the car to take away for a spot of listening.

A bootful of CD history: from top to bottom CD104 (1984), CD150 (1985) and CD160 (1986)

And after they'd been cleaned up a bit by our expert photographer for the shots you see here, all three got some use at home, just to see how they sounded.

But first, a look at all three machines, and what was immediately obvious was that the CD104 was substantially heavier than the later machines, the reason for which became clear when I popped the lid to look inside: no plastic!

Full metal player

Anything inside this player that could be made of metal, is made of metal, meaning it has a substantial transport mechanism and an overall feel of solidity somewhat lacking in its featherweight descendants.

There's also a massive heatsink on the back to keep the power supply section regulators cool and performing as they should.

However, a look under the lid will tell you this design is far from the ‘shortest path’ layout favoured in modern equipment – cables seem to run everywhere!

However, with that that solidity of build it’s no wonder the CD104, with its novel two-way (up/down/left-right) rocker panel for play/pause and track skip, became the basis for many tuned machines.

These include Mission's DAD7000 (reviewed in Gramophone, left) – although that model replaced the square rocker panel with four smaller buttons – the Marantz CD-34 (below), and several others including models under the Revox and Schneider names.

It was also a best-selling machine for Philips – maybe that What Hi-Fi? Award helped a bit!

Our CD104 had been shipped to a retailer in Swindon somewhere back in the mists of time, according to an address stamped on the box, and aside from obvious signs of wear on the most-used controls – oh, and that recalcitrant drawer, probably fixable if the correct parts, most likely a belt, could be obtained – was very much in working condition.

Earliest player, the Philips CD104, came complete with original box and manual

By comparison with the hefty CD104, tipping the scales at 7kg, the CD150 was both much lighter, its 3kg all-up weight down to much greater use of plastics in the mechanism and the front panel, and a glass-fibre reinforced chassis instead of the CD104's diecast aluminium.

As already mentioned, it was built down to a price, too, launching at £229 and falling to £199 before the CD160 appeared to sit above it, again at £229.

The CD160 wasn't the first Philips machine to make the move from 14-bit conversion to 16-bit, using the TDA1541 DAC: the new chipset had already been used in the more upmarket CD450 and CD650.

It was, however, the first mass-market Philips machine with this specification, and the marketing department went a bit bonkers with the glitzy trim and very obvious '16 Bit Fourfold Oversampling' badging on the front of the player.

Now when the CD104 was first launched it was £329, or about £875 in modern terms; the CD160, at £229, would be the equivalent of about £550 these days.

And if ever you needed evidence that hi-fi hasn't just defied inflation, but has actually got ever more affordable, bear this in mind: the entry-level player I chose to pitch against the Philips machines, the £300 Cambridge Audio Azur 351C (below), would have been £125 in 1986 terms, and £100 in 1982 money.

In other words, a good entry-level CD player is now less than half the price it would have been 30 years ago: given that the total rate of inflation since 1982 is just over 200%, that's not bad going!

OK, OK – so how do they sound? Well, anyone hoping to hear that the early machines are almost comically bad compared to today’s digital marvels is going to be disappointed; but then again so will those suffused by a rosy glow of nostalgia and feeling either that little of any progress has been made, or that those players of the past set standards unmatched by modern machines.

A bit vague in its old age?

The earliest machine (the CD104) sounds a bit vague by comparison with the very latest hardware, and indeed the most recent of our trio, the CD160 – but then both it and the CD150 are using the original 14-bit DAC technology with which CD was launched. The balance here is smooth, but fairly dynamic, but what’s gone AWOL is the presence and sparkle that makes the best of modern CD players sound so involving.

If you want, the CD104 sounds a bit like a high-bitrate MP3 file – the music’s all there, but some of the magic and vitality is missing.

Nonetheless, it’s not hard to hear just what appealed so much to early CD buyers, used to the crackles and pops of poorly-kept LPs or the almost inevitable hiss of cassette: there’s nothing to get in the way of the music here, even if it’s clear with the benefit of hindsight that recordings still have much more to give.

The CD150 shows that the Philips engineers were able to keep much of that sound quality while bringing prices down – important given that CD players were still three or four times the price of a sensible turntable/cartridge set-up such as the Sansui SR-222 MkII (below) with which I first started listening seriously back at the beginning of the 1980s.

Given that and the price of discs, something had to be done to draw more buyers into CD, and faced with the rapid price-cutting being done by the Japanese brands, Philips responded with the CD150, and then the CD160.

So while the CD150 was, as already noted, obviously less expensive to build than the CD104, the sonic balance remains much the same, only taking an obvious leap forward with the arrival of the 16-bit CD160, which suddenly seems to open up the sound at the top end of the frequency range, as well as giving greatly improved dynamics.

By comparison, the 14-bit machines can sound rather cautious with big orchestral works or the kind of hard-hitting electronic bass yet to be refined and used widely when these machines were first sold.

That said, the CD160 can sound a bit shrill and glassy up in the high treble, not to mention giving cymbals and orchestral tuned percussion a bit more ‘splash’ than we’re used to today, rather than a crisp presentation of the instruments’ sound.

There’s no doubt that even entry-level CD players of today can deliver high frequencies with greater bite and sting, adding to the sense of excitement, without the rather fatiguing edge apparent in the CD160, while delivering the sense of air and space, especially with atmospheric ‘live’ recordings, that almost entirely eludes the earliest players in our trio.

We've gained focus, power and flow

Switch from the CD160 to the Cambridge Audio Azur 351C, for example, and it’s immediately clear that you’re hearing so much more of the recording, from instrumental textures to the speed and attack of the music, while also getting tighter, more solid and convincing bass, a clearer soundstage picture – the old machines can sound a bit ‘left channel, right channel’ – and greatly improved focus.

In other words, more of an impression of real musicians rather than miniature ones...

What’s more, switching from old to new shows that the latter is much easier to listen to, having greater smoothness and musical flow, and lacking the sometimes slightly ‘technical’ sound of the old machines.

For all that, none of these elderly players would actually disappoint when listened to in isolation, and as usable historical artefacts available for bargain money any would make a good choice for those wanting a taste of where CD came from.

Compare the price of one of these players with what you’d have to pay for a high-quality turntable from the past, and they begin to look like something of a bargain, not to mention a fun way of seeing whether you think your state of the art CD player – or indeed streaming set-up – really shows we've made much progress since digitally-stored music became available to all.

Me? I think I’ll stick to my thoroughly modern disc playback and music-streaming set-up, appreciating how far digital music playback in the home has come in the past thirty years.

Mind you, I might hang on to that CD104, just for novelty value, and see whether I can coax that drawer back into life.

Oh, and I may keep my eye out for an original Philips CD100-based top-loading machine – you know, just in case I stumble across one for silly money in the hands of someone who doesn’t know what they’ve got.

And then perhaps…

Written by Andrew Everard

Andrew has written about audio and video products for the past 20+ years, and been a consumer journalist for more than 30 years, starting his career on camera magazines. Andrew has contributed to titles including What Hi-Fi?, Gramophone, Jazzwise and Hi-Fi Critic, Hi-Fi News & Record Review and Hi-Fi Choice. I’ve also written for a number of non-specialist and overseas magazines.