How does a vinyl record make a sound?

From groove to speaker, this is how vinyl records work

Have you ever had a close look at a record and wondered how that tiny groove can result in the sound you hear through your stereo speakers? In many ways, it seems like witchcraft, but it is of course good old analogue science.

While the basic idea goes back almost 150 years, to Edison’s phonograph, the record as we now know it is more like half that age. Columbia Records launched the first 12-inch LP in 1948, with the first public demonstration taking place on June 20th at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, New York. The rest, as they say, is history.

Loads of new music formats have appeared since then, and many have been predicted to kill off the decidedly old-school vinyl format, yet it simply refuses to die – while many of those newer formats quickly went the way of the dodo.

There are many reasons for the longevity of vinyl, but we like to think that one of them is that it’s simply a wonderful piece of engineering that, even today, seems just a little too unlikely to actually work. But work it does – and, with the right equipment, to a fabulous level.

Whether you're a seasoned collector or you are looking to purchase your very first turntable, a little knowledge of what's going on can only be a good thing.

The groove

A record's groove – and there is generally just one that spirals gently to the centre of the disc – is tiny, usually around 0.04-0.08mm wide (depending on the level of the signal). If you were to unravel it, the groove on a 12-inch LP would extend to a length of about 500 metres.

The two sides of the groove sit at right-angles to one another, with the point of that angle facing down. Each side of the groove carries what can only be described as wiggles that represent the right- and left-channel audio information.

Get the What Hi-Fi? Newsletter

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

The side closest to the outside edge of the record carries the right-channel signal. This information can be stored in an area as small as a micron (one-thousandth of a millimetre), so the scale of the task to retrieve it is immense.

This also explains the sensitivity of record players to external vibrations and other disturbances.

The cartridge

It’s the job of a cartridge to track the groove. More specifically, it is the job of the stylus tip to do so.

The tip is made of a very hard substance, normally diamond. But don’t get too excited – it’s industrial diamond rather than the really valuable stuff, which means it lacks the purity of the gems you might find in jewellery.

This diamond tip is usually shaped into a small point – though there is a variety of shapes the tip can take – that sits in the record groove and follows the wiggles as the record turns.

The nature and degree of the stylus’s movement are what translate into the varying frequencies and volume that you hear through the speakers. This movement is carried through the cantilever – the shaft to which the stylus tip is attached – and into the cartridge body.

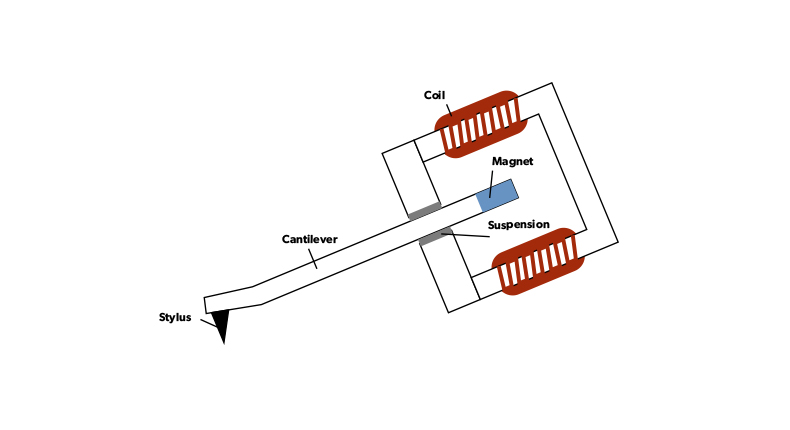

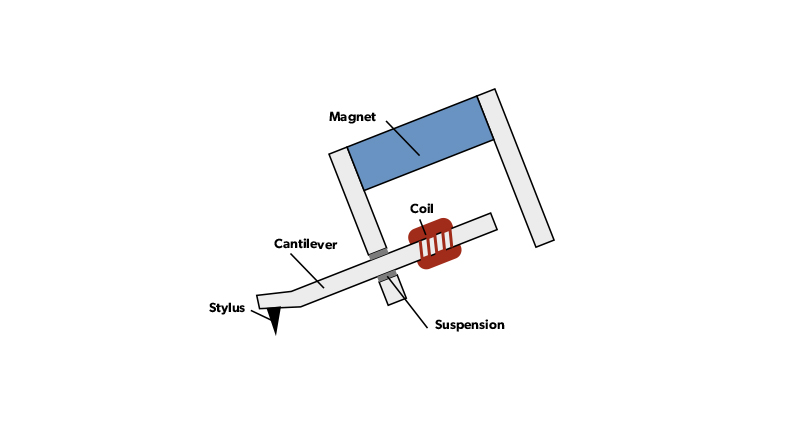

There are two types of cartridge: moving magnet and moving coil. They both work on the principle of using movement to induce current thanks to magnetic fields.

But, as the names imply, in one the magnet moves to induce current while in the other the coil does and the magnet is fixed. So, assuming we’re talking about a moving magnet cartridge, in the case of our example a tiny magnet is attached to the hidden end of the cantilever; as the stylus tip moves around, it does too.

The magnet’s varying field causes current to flow in the tiny coils positioned close by, and this is the signal that comes out the back of the cartridge to be fed into your amplifier. Or, if your amplifier is a line-level device, as many are, a dedicated phono stage.

- Read all our cartridge reviews

- How to change the cartridge on your turntable

The phono stage

What exactly does a phono stage do? The physical limitations of vinyl mean that the original signal has to be altered before it can be recorded – low frequencies are reduced in level and the highs are boosted.

The curve that governs this equalisation was set by the RIAA (Record Industry Association of America) years ago. If you’ve ever plugged a turntable directly into a line-level input you know you get a very quiet sound – and also one that is thin and bright, with no bass frequencies to speak of.

Every phono stage has the reverse response built into it – one that boosts bass and flattens treble to exactly the right degree. The result should be a tonally even presentation.

A phono stage is also an amplifier. Cartridge signals can be as low as a thousandth of a volt (CD’s output is specified at 2V) so the signal has to be amplified massively before the line-level stage of an amplifier can take over.

So rather than the witchcraft we always sort-of suspected it must be, getting a sound from a vinyl disc turns out to be nothing more than fiendishly clever.

It's worth bearing in mind the ingenuity at play when you next carefully place the tip of your stylus into the groove of a LP – but don't dwell on it for all that long. After all, there's music to be listened to.

MORE:

Here's our guide to the best turntables you can buy at every budget

Our comprehensive guide on how to set up a turntable

And our tips on what to consider when choosing a turntable for you

Ketan Bharadia is the Technical Editor of What Hi-Fi? He has been reviewing hi-fi, TV and home cinema equipment for almost three decades and has covered thousands of products over that time. Ketan works across the What Hi-Fi? brand including the website and magazine. His background is based in electronic and mechanical engineering.

-

Navanski Nothing wrong with the article per se but there are a few points which I think are worth mentioning.Reply

Firstly, there is no mention of the way in which a master for vinyl is created. I always think this is worth a few lines in order to explain that most tonearms are a compromise in as much as they do not mimic the way a master is cut. Only tangential tonearms 'read' the groove in the same way as the master is cut.

The other point is that the data density varies on a vinyl disc. The outer portions of an LP are travelling at up to twice the speed of the inner portions of the disc. As a consequence the inner portions of the disc are crammed with data when compared to the outer sections. This doesn't necessarily impinge on sound quality but there are cases of LPs being re-arranged to place lower fidelity tracks on the inner sections.