A brief history of Audio-Technica's 60 years

Born of a mission to bring the hi-fi to the home

This feature originally appeared in Sound+Image magazine, one of What Hi-Fi?’s Australian sister publications. Click here for more information on Sound+Image, including digital editions and details on how you can subscribe.

Preparing company histories can be a fascinating endeavour: this writer enjoys the rabbit holes down which one can scurry, finding a book or an article lost in time or on the web that will add a small detail missing from official histories, or a revealing quote from back in the day that unlocks what a company was really trying to achieve.

A fair part of this Audio-Technica history is based on Japanese-language sources, which was fun, and we should perhaps start by saying that any errors here are entirely our own, or those of Google Translate.

We anticipated a history of cartridges, headphones and pro audio gear. But it was soon clear that what has driven the development of that equipment is Audio-Technica’s ongoing innovation in technologies.

Working out how to implant a diamond needle without crushing the tip of the pipe cantilever was key to its initial success in cartridges, while in the 1980s the company’s commercialisation of PCOCC (single crystal high-purity oxygen-free copper) allowed any number of products to take a step forward in quality.

There are also surprises. Who knew that Audio-Technica is big in automatic sushi-making machines? That it dabbled, temporarily it seems, in home glue-making machines? And that it has a successful TechniClean brand with everything from hand cleaners to industrial clean-room tech?

Much as we definitely now want a compact nori-rolling machine of our own, we feel constrained by the focus of our publication to use the space here for the more hi-fi-focused origins of this Japanese company which, this year celebrates its 60th anniversary. So let’s start, as Mary Martin was singing so sweetly in The Sound of Music on Broadway back then in 1962, at the very beginning. It’s a very good place to start.

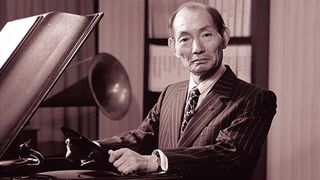

Audio-Technica Co. Ltd., then, was founded on 17th April 1962, with a capital of one million yen and three employees, in addition to the founder Hideo Matsushita working in a rented one-storey private house in the Shinjuku district of Tokyo.

Get the What Hi-Fi? Newsletter

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

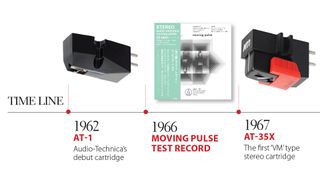

Its launch product was the AT-1, a moving-magnet cartridge that claimed to “revolutionise sound quality” with a world-class technology that implanted a diamond needle without crushing the tip of the pipe cantilever, and which quickly became a bestseller. The founder remembered that he and his staff “worked late each night, stopping only for dinner at the ramen shop in front of the premises.”

By the time he founded Audio-Technica, mind you, Hideo Matsushita was a 42-year-old vinyl fan. How did he get that way?

Gummy shoes and car tyres

If Hideo Matsushita had a mentor, it was likely Shōjirō Ishibashi, a tailor and entrepreneur who took over his family’s tailoring business at the age of only 17, and who then achieved great success in the 1920s by using new gum arabic adhesion

technology to create working-class footwear (under the brand name Asahi Jikatabi). Shōjirō achieved still greater fortune by anticipating the growth of the automobile in the 1930s and founding Bridgestone Tire Co.

With his newfound wealth, Ishibashi began amassing an art collection of European and Japanese Western-style paintings and, after experiencing American art galleries in the post-War period, he decided to create a public art space in Tokyo across the entire second floor of the building he was building – Japan’s first nine-storey construction, The Bridgestone Centre.

This ‘Bridgestone Gallery’ opened in January 1952, not only displaying his art collection but also playing host to events and activities, lectures by experts and guests, concerts and recitals. It became a centre for art fans and artists seeking local and international culture in those post-War years.

The Bridgestone Gallery opened in the same year that Hideo Matsushita, then aged 32, left his home in Fukui Prefecture and came to Tokyo; he began working at Ishibashi’s Gallery through an introduction by his uncle. The museum’s director urged him to run what he called ‘LP concerts’, where people would hear vinyl records played on high-quality audio equipment.

“These were much more successful than anyone imagined,” remembered Matsushita later. He was moved by the reactions of guests to the music, but as he continued the concerts over a decade at the Gallery, he became frustrated that the expense of high-fidelity listening prevented more people from experiencing it at home.

And from there, you can draw a straight line to the formation of Audio-Technica, which Matsushita founded with that express purpose – to deliver in the AT-1 an affordable cartridge that would bring a higher quality of audio to the homes of many more people, a goal that directly echoed the public spirit of Shōjirō Ishibashi’s Gallery (which is today the Artizon Museum, still operated by the Ishibashi Foundation he set up).

Rapid growth

Audio-Technica did well from the start. The AT-1 and the higher-end AT-3 both became ‘hits’, and the company also started delivery of cartridges to domestic audio manufacturers.

The staff quickly grew to 20, outgrowing its first premises, so that after three locations in Shinjuku, the company building was relocated to Machida City, Tokyo.

More cartridges were launched – the stereo AT-5, the mono AT-3M – and tone-arms were added in the AT-1001, AT1003, and the broadcast-specification AT-1501 and AT-1503, with which the company began supplying NHK and other broadcasting stations.

To help set up their products and to prove their quality, a test record entitled Moving Pulse (AT-6601) was released in 1966, including frequency response checks, left-right channel idents, a speaker phase check and the all-important silent track. “Listen to stereo test records with your ears!” implored the inside label.

Hand in hand with product development, Audio-Technica was already taking an advanced angle on press and marketing, moving quickly from technical advertising to more mysterious and artistic presentations of their brand and products, including enlisting popular children’s author Shinta Chō for illustrations. (By the 1960s Chō was already known for his ‘Talking Omelette’ cartoons, but he would become most revered by children the world over for 1978’s The Gas We Pass: The Story of Farts.)

The V factor

In 1967 the company made another technological advance, releasing the AT-35X as the first ‘VM’ type stereo cartridge. This patented Dual Moving Magnet design duplicated the V-shaped structure of the cutter head used to cut the modulations into the record groove during the record manufacturing process. A Dual Magnet design allows the stylus assembly to read these modulations back using two small magnets

precisely positioned on the stylus cantilever to match the positions of the left and right channels carved into the groove walls. Compared to larger single-magnet designs, the Dual Moving Magnet ensured improved channel separation, extended frequency response and better tracking.

This design rapidly became a backbone for growth in exports around the world, as the VM patent was extended across Switzerland, Canada, the UK, US and West Germany.

The company started operations in a new factory adjacent to the Machida head office, using a new mass-production technology incorporating precision moulds. The AT-VM3 was the first cartridge manufactured using this process and rapidly became a bestseller beyond even the AT-3.

“The Model AT-VM3 is a new type stereo phonographic cartridge,” announced its product manual. “The cantilever is made of a tube of hard duralmin only 50 microns thick and of very low mass.

Repeated tests with both carefully calibrated instruments and actual hearing, using the cartridge with the very best of high fidelity equipment, all bear out the superiority of the AT-VM3.”

Soon afterward a tapered cantilever was developed, first released on the high-end VM-type stereo AT-VM35 cartridge. The tapering technique was also applied to the AT-1007 tonearm, the world’s first with a tapered pipe.

The 1970s

By now, Audio-Technica was looking to position itself as a comprehensive audio manufacturer. There were movements into magnetic tape heads, and also into four-channel sound, with the AT-VM35F cartridge supporting four-channel records via wideband playback over 45kHz, more than double the conventional high-end.

But it was earlier research into high-quality stereo headphones that began to bear fruit in the mid-1970s, with a new AT-700 series of headphones delivering both conventional open dynamic designs in the AT-701, 702 and 703, and electret condenser type headphones in the AT-705 and 706 (effectively electrostatic designs without the high voltage requirement, requiring only an impedance-matching adapter unit).

1977 brought the second-generation models of dynamic headphones in the ATH-3, ATH-4 and ATH-5 but, more importantly, as the company celebrated 15 years, Audio-Technica developed and released the dual moving-coil MC-type AT-34 stereo cartridge, which performed well in the market in opposition to Danish Ortofon’s iconic MC 20, despite the Danes issuing moving-coil designs since their beginnings in the late 1940s.

Another new avenue was opened up in 1978 with Audio-Technica moving into the commercial microphones market, launching eight AT800 series designs at once, from Laveria to shotgun microphones.

Carts, copper and CDs

The company didn’t neglect its core cartridge business, however, with two key designs released at the end of the decade. In 1978 the AT25 was released, with an integral structured body housing a VM cartridge and, crucially, featuring a newly developed toroidal power system.

This was further developed for the AT120E/G from the new AT100 series in 1979, a VM cartridge that debuted a low-loss para-toroidal power system in which a metal magnetic shield was placed between two Omega (broken circle) toroidal coils in parallel – hence the name ‘para-toroidal’.

In 1981 Audio-Technica introduced a moving-coil cartridge that made full use of the ultimate material: diamond. The AT1000 featured a diamond cantilever, delivering an integrated structure of natural diamond from the needle tip right to the base of the vibration system.

“With this vibration system, a samarium-cobalt magnet, and a magnetic circuit of vanadium permender yoke, an output voltage of 0.1mV is obtained with a low impedance of 3.5 ohms,” marvelled issue 61 of Japan’s Stereo Sound.

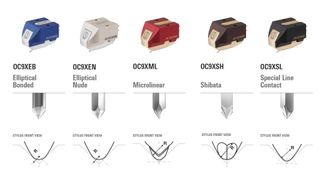

The long-selling AT33E was released in the same year, and in 1987 the AT-OC9, the original cartridge model from which evolved today’s fourth-generation AT-OC9X series, now available in five colours, five stylus profiles and with different yoke and cantilever materials (pictured below).

The 1987 original used a special elliptically-polished nude diamond on a gold-plated beryllium cantilever, for a result hailed at the time as the “biggest bargain in audio history! Worth far, far more than its humble price!”

But the AT-OC9 had another secret weapon, one shared with the latest AT33ML version of the AT33 and other cartridges too. This was the commercialisation of a dream material – single-crystal high-purity oxygen-free copper, known as PCOCC or ‘pure copper Ohno continuous cast’ wire. The ‘Ohno’ was Professor Ohno from the Chiba Institute of Technology in Japan, who had developed a new process for refining copper.

Normal copper forms a polycrystalline structure when the hot molten metal is poured into a cooled mould for extrusion. The OCC process instead keeps the copper heated during casting and extruding, resulting in a larger crystal size and increased purity, the copper lacking grain boundaries down the length of the resulting wire. Audio-Technica claims to have been first in the world to put PCOCC to practical use; in the AT-OC9 it was used in both the coil wires and the terminals.

But just as this exciting development was being realised, there was a rising existential threat to the entire cartridge business of Audio-Technica. The Compact Disc had been released in 1982, and by 1987 the silver discs were outselling vinyl for the first time. It was the beginning of what many believed would be the total demise of vinyl, and so with it the end of any cartridge and tone-arm business of Audio-Technica.

The company did initially pivot, conducting research and development into semiconductor lasers and optical pick-ups, and delivering actuators for both LaserDisc machines and CD players. But these would never have the same large-scale replacement business as occurred with stylii and cartridges in the vinyl world.

New times, new markets

As we know today, vinyl survived, and is now thriving. While many cartridge makers either folded or switched businesses during the lean years, Audio-Technica managed to diversify its business sufficiently to maintain its cartridges at a lower level, until the revival allowed it to reap the rewards of its long-term experience.

Those other markets include the headphones and microphones into which it had already diversified. A ‘Point’ series of lightweight headphones were released for the cassette player market as the Sony Walkman hit its heights through the 1980s.

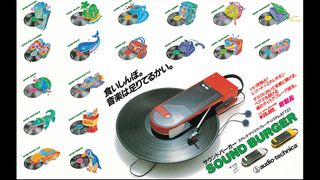

Audio-Technica also countered with the remarkable SoundBurger portable turntable in 1986, but began looking increasingly to professional markets, releasing compact speakers and mixing amplifiers, as well as pro-oriented headphones and microphones.

It entered the high-grade car audio accessory business. And the company also looked sideways, its founder encouraging new ideas that led to the ASM50 “Nigirikko” sushi rice ball maker for home use, and the ASM300 “Sushi Maker” for commercial use. This line has developed into the subsidiary AUTEC, today number two in a 50-country market for sushi-making machines.

In 1993, founder Hideo Matsushita took the position of Chairman, while his son, Kazuo Matsushita, became Audio-Technica’s President. The company continued its success in microphones, and to this day has supplied successive Olympics with the equipment used to capture the sound of sport.

It introduced increasingly high-quality home headphones, championing the use of natural wood in the 35th anniversary ATH-W10LTD and the W series that followed. In 2006-2007 it released its first earbuds and noise-cancelling headphones, and more recently has enjoyed success turning its studio models such as the ATH-M20x and M50x into accomplished Bluetooth wireless headphones.

A legacy of sound

One year after the company’s 50th anniversary, founder Hideo Matsushita passed away aged 93, on 5th March 2013. By then he would have seen the revival in vinyl’s fortunes, with the company already catering to a fresh generation discovering the joys of the black stuff and launching new models including 2012’s 50th-anniversary AT50ANV, the first non-magnetic-core MC cartridge.

Hideo Matsushita had always maintained his enthusiasm for playing music and, indeed, had amassed quite the collection of vintage gramophones. According to Mono & Stereo, his collection had been inspired by a collector who had a gramophone displayed in a corner of a shopping mall in Ohio, back when Audio-Technica US had first been established. Later he met the large-scale collector Sammlung W. Schenker of Zurich, eventually taking over his collection of more than 100 gramophones.

After his death, his son Kazuo Matsushita donated part of the gramophone collection to the Children’s History and Culture Museum in his father’s home prefecture of Fukui so that they could be enjoyed by all who visit.

Meanwhile the rest of us, of course, can enjoy Hideo Matsushita’s legacy every time we don a pair of Audio-Technica headphones, or unsleeve an LP and slip the vinyl onto an Audio-Technica turntable or under an Audio-Technica cartridge, to experience the same joys he had witnessed in audiences during his ‘LP concert’ evenings long ago in Shōjirō Ishibashi’s Bridgestone Gallery.

Sixty years of sound, then, from a company that keeps on giving.

- Read What Hi-Fi?'s Audio-Technica reviews

Jez is the Editor of Sound+Image magazine, having inhabited that role since 2006, more or less a lustrum after departing his UK homeland to adopt an additional nationality under the more favourable climes and skies of Australia. Prior to his desertion he was Editor of the UK's Stuff magazine, and before that Editor of What Hi-Fi? magazine, and before that of the erstwhile Audiophile magazine and of Electronics Today International. He makes music as well as enjoying it, is alarmingly wedded to the notion that Led Zeppelin remains the highest point of rock'n'roll yet attained, though remains willing to assess modern pretenders. He lives in a modest shack on Sydney's Northern Beaches with his Canadian wife Deanna, a rescue greyhound called Jewels, and an assortment of changing wildlife under care. If you're seeking his articles by clicking this profile, you'll see far more of them by switching to the Australian version of WHF.