Sound+Image Verdict

Big headphones with long battery life and a clear emphasis on both protecting and potentially correcting hearing. The sound is powerful if not sparkling, competitive at the price against the best-regarded competitors. And if you’re a drummer, they're a unique proposition.

Pros

- +

Solid sound & design

- +

Both protective and corrective

- +

Special ANC for drummers!

Cons

- -

Price

- -

Some common options missing

- -

Could be more open-sounding

Why you can trust What Hi-Fi?

This review originally appeared in Sound+Image magazine, Australian sister publication to What Hi-Fi?. Click here for more information on Sound+Image, including digital editions and details on how you can subscribe.

Hardly anyone can confidently pronounce it, but there can be very few music lovers who do not know the name and the logo of Zildjian, just as there are very few brands which are as synonymous with a single type of product as is Zildjian. This recognition is born both from quality and from longevity: while a good few hi-fi companies have recently been celebrating 40th or 50th anniversaries, last year Zildjian celebrated the 400th anniversary of its founding in Turkey.

Almost inconceivably, after four centuries and a move to the USA, it is still run by Zildjian family members. The secret cymbal “formula” had been passed from each head of the Turkish Zildjian foundry to the next male heir… until in 1927 the next male heir was Avedis Zildkina III, who had already emigrated to the USA to become very successful in the American candy-making business, thank you; what did he want with cymbals?

But Avedis III’s wife encouraged him to make enquiries at local music stores, where he was amazed to find that even in Boston everyone knew that the best cymbals in the world were made by Zildjian in Turkey.

So he opened a foundry in the US in 1928, selling first to the US Army’s marching bands, and then to dance bands, big bands, and jazz bands, during which expansion of business he established a virtuous feedback circle in order to “get drummers what they need”, a philosophy which led to the diverse shimmering discs of gold gracing the kits of the world’s greatest drummers ever since.

But one has to ask why, after four centuries of foundry work, Zildjian has decided to make a headphone?

Build & facilities

Why indeed. A branding exercise? Not entirely. Zildjian did that eight years ago, through an Australian connection indeed, authorising a Zildjian special edition of Audiofly’s AF240, that Aussie company’s first overear headphone as it launched into the US market; it was a very fine headphone at an excellent price.

Zildjian also currently offers a single in-ear monitor model, intended for musicians on stage, or in the studio, or in practice. The company also makes those essential tools for every sensitive drummer: ear plugs (in light and dark flesh tones, so your audience will never know).

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

But this seems to be its first ever foray into overear headphones which are sold entirely as Zildjian’s own. And it has aimed high, with a luxurious build that combines elements of sculptural metal yoke styling a bit like Bowers & Wilkins’ earliest luxury headhuggers, but here with larger and rounder headshells more in the Beyerdynamic tradition, though very wide in their internal padding so that the space for your ears is relatively small.

The padded headband itself is a massive piece of metal, marked with divisions into which the headband ratchets in a series of bumps as you pull them out. Being gold, the band and yokes might be considered rather Chinese bling – such shining solidity graces many headphones aiming for that luxury market, such as Mont Blanc, as well as lesser designs hoping to appear more luxurious than they are. But of course here it may have been chosen to reference the gold of Zildjian cymbals.

The yokes arrive covered with protective rubber tubes, and when removing them there’s one plastic bit which doesn’t come off: remarkably this houses a minijack socket inside its end, a cleverly-disguised connection point if you’re listening with the provided cable (nicely branded; the USB-C cable is shown below), rather than wirelessly.

Type: closed circumaural dynamic wireless with ANC

Connections: Bluetooth 5.3 (SBC, AAC), minijack analogue, USB-C charging

Battery capacity: 680mAh ~50 hours playback

Drivers: 40mm dynamic

Quoted frequency response: 7Hz-22,000Hz

Finishes: Black, Sandstorm, Midnight

Weight: 357g

Cabled listening might be expected to be an advantage, as the Bluetooth spec here is limited in quality: version 5.2, but using only the SBC and AAC codecs. There is no proprietary aptX or LDAC or other codec available to raise the bit-rate above the 256k AAC to which iOS devices will default, while Android users are left with only the base-level SBC codec. (Including a proprietary codec might have raised this as far as CD quality.)

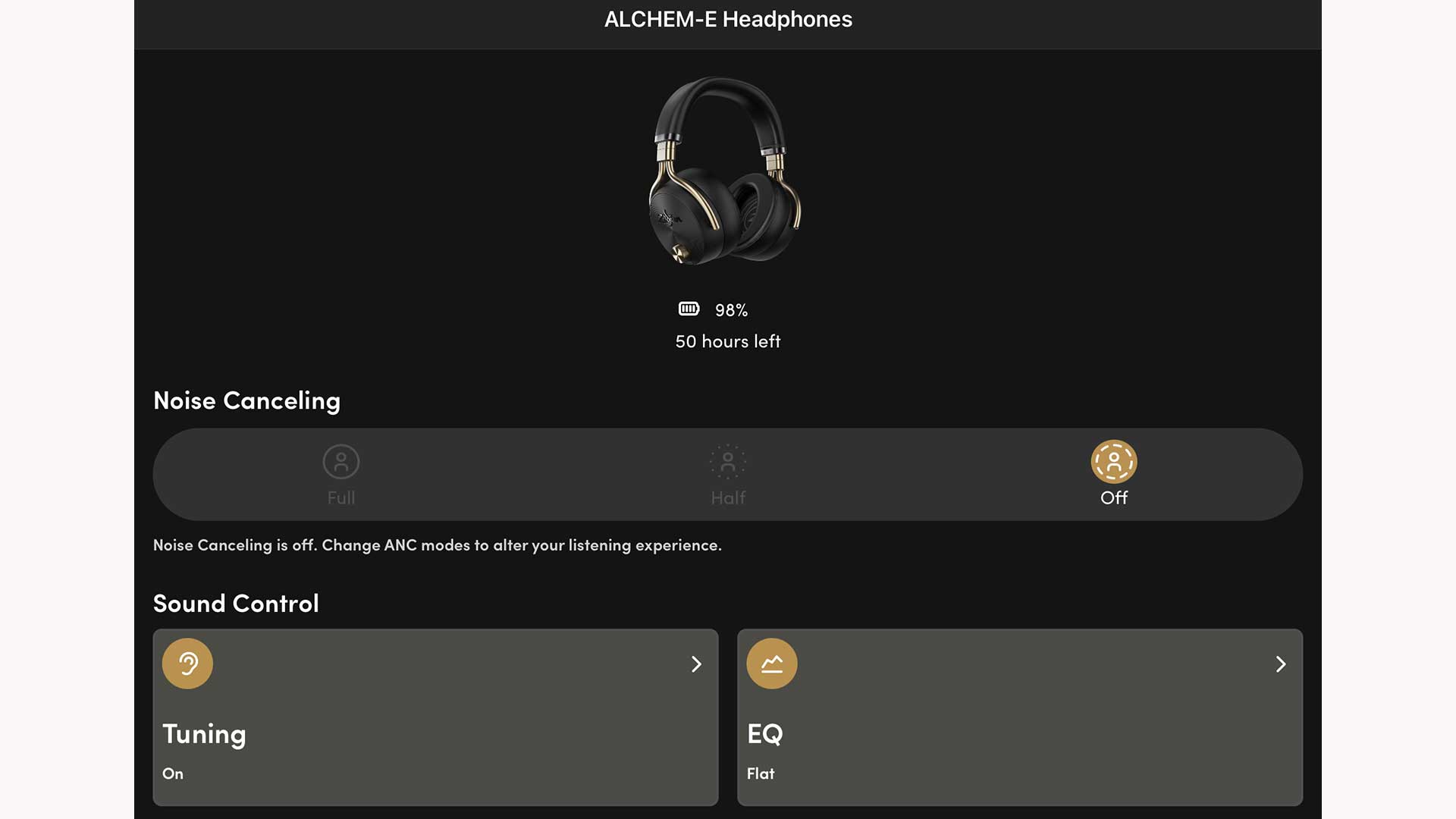

Some headphones can play digitally via their USB-C charging connection; here the headphones never appeared as an output when we plugged them into our laptop, so we conclude the USB-C socket is for charging only. There’s good capacity of 680mAh in the internal battery; 15 minutes is enough to charge it to 15%, two hours for a full charge. Zildijian doesn’t give an approximate battery life in specs, but the app shows how much is left, and it began up at 50 hours, so that’s a minimum, and that’s impressive battery life!

Those LED segments show remaining charge when you first power up: four or three greens, two ambers, or a single red segment alerting you to the need to plug them in or move to the cable.

Controls are nicely intuitive; when you press the power button they don’t announce “On”, or “Battery 80%”, as is common; instead there are little open or closed hi-hat twiddles (ba-da-dum-tish!) to indicate turn-on and turn-off. Rising or declining LED segments confirm which choice you’ve made. Holding the power button puts the headphones into pairing mode.

The button above the power, on the other side of the four LED segments, selects the level of noise-cancelling, shuttling through three levels announced by one to three electronic bleeps: one for ‘Off’, two for ‘Half’, described unusually as providing “a protective, full-frequency acoustic drumming experience…”, while three bleeps means Full, “designed for isolation, protection on airplanes”.

Finally there’s a control knob on the outside of the right headphone shell; knobs have become fashionable since the ‘digital crown’ on Apple’s AirPod Maxes showed how very useful such a spinning wheel can be. Here it turns for volume, presses once, twice or thrice for pause/next/last track, and you can even press, hold and turn to scrub through tracks (if you’re lucky).

The supplied case will look a bit odd to many, slightly testicular (compared with Apple’s bizarre headphone case which looks like a bra on one side and a butt on the other). We thought perhaps the rubberised outer and fabric lining was mimicking Zidjian’s protective cases for cymbals, but we couldn’t find anything similar in their ranges. So just a bit weird, then, the case.

ANC good, different

We were soon powered up and connected. With power buttons you normally need to hold them just a little time to power them down again, to avoid doing so accidentally. Not so here, so it’s nice and quick to turn off, but rather too easily done when you’re feeling for the ANC button or adjusting the headband.

Besides, when auto-standby is selected via the app, they’ll turn off after any period without music anyway; you can set the duration to 15, 30 or 60 minutes – or never.

The ANC is solid, especially on lower (aircraft drone) frequencies; the ear padding is so substantial that even with the ANC turned off there is significant passive isolation against higher frequencies, so the combination of passive and ANC is effective.

But there’s something else going on here as well. We gather that Zildjian hasn’t just used the ANC on a Bluetooth receiver chip as supplied, it has developed its own bespoke ANC, which is specifically tailored to the sound of drums.

“Traditional ANC software does not work with acoustic drums,” it says. “When you try to drum with regular ANC headphones, they clip, some frequencies (i.e. cymbals) may be completely inaudible, while other frequencies (e.g. kick drum) will still come through. So they’re impossible to use while playing drums.”

Sadly we didn’t have a drum kit handy to check all this out. But it’s an interesting pointer to how and why these headphones were developed – their name, ‘Alchem-E’, comes from Zildjian’s sideline in electronic drum kits; perhaps these headphones were developed to match, and in reaching us are breaking out into the wider world. The ANC here seems not primarily intended to block everyday noise, but specifically a drum kit, either to remove them entirely (perhaps while using the headphones for foldback), or to deaden the sound simply to protect themselves against the power of their own drumming.

“At 100% ANC, our headphones block out the acoustic drum kit almost entirely,” says Zildjian. “There is no clipping, and the sound of the kit is evenly blocked out.”

But at 50% ANC, “our headphones work like a damper pedal on a piano — the entire drum kit is audible, but quieter. There is no clipping, and all parts of the drum kit are evenly dampened.”

All this reveals these headphones to have been designed as a specialist tool. Drummers and percussionists most definitely need hearing protection; drums can exceed 115dB. No surprise, then, that many drummers later in their careers need hearing correction: they are more than four times more likely to have sustained hearing damage than the general population. These headphones provide both protection (see above) and correction (see below).

They are perhaps more for drum practice than performance. If they were intended for foldback, we would wonder whether Bluetooth’s latency on SBC and AAC would be low enough not to annoy drummers. So why no low-latency codec to help with that? Or would Wi-Fi/UWB be a better option?

These questions are not for us when reviewing in a more-or-less hi-fi listening context. We just want to know how the ANC works when we’re listening to Alex The Astronaut on the bus commute. And happily, as already noted, the noise-cancellation seems to work just fine in everyday life, in addition to the rare feature of fully protecting you against any passing drum kits.

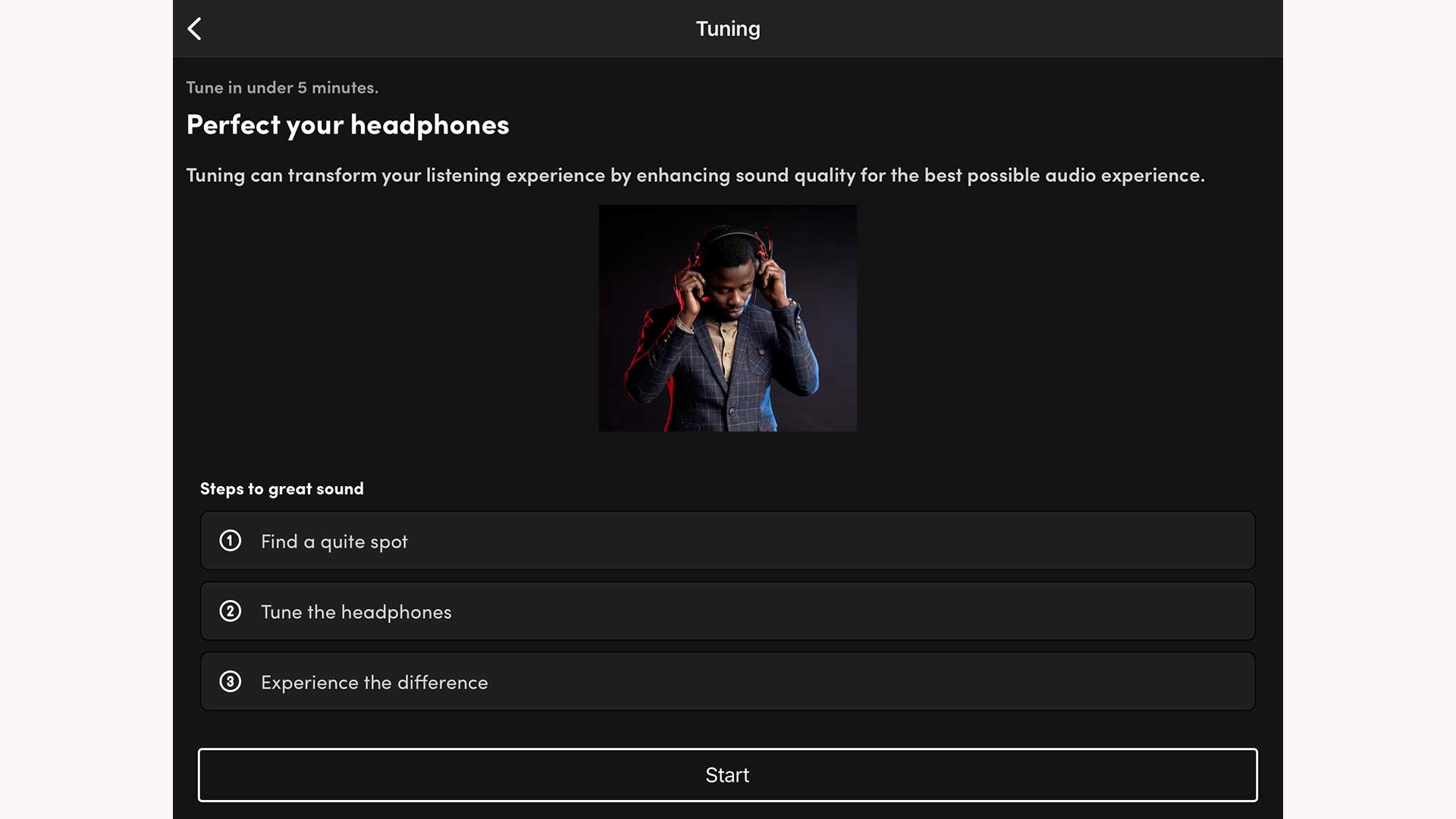

Perfect Tune personalisation

The other key feature is ‘Perfect Tune’ personalisation. This involves sitting in a nice quiet place, then listening for test tones while pressing a giant ‘Z’ button on the screen of your phone or tablet. This enables the software to create a hearing profile which it can then reverse-engineer to create your ideal sound.

“Find new parts in your favorite song,” says Zildijian. “Hear notes you didn’t know were missing.”

Before we’d even started the process, we recognised the personalisation system; we have used it before. This is another Australian connection, originating from sunny Brisbane, where two doctors formed ‘Audeara’ back in 2014, aiming to make medical-grade ‘audiograms’ more accessible through just this kind of app; they used Kickstarter to develop headphones with their system of hearing personalisation built in. As Audeara put it when we tested their A-01 headphones back at the end of 2018, “Audeara measures each ear — and knows what it hears well and not so well…” then “modulates the playback to match each ear’s audiogram”, with the result that “you hear and feel so much more without having to add volume”.

That last part is important, because if the Audeara system can prevent you turning your music up to hear the bits your ears are missing, it’s potentially protecting your ears against further deterioration.

Audeara is far from alone in this market; the German ‘Mimi Defined’ system launched at a similar time. There is a projected $10bn market for such high-street ‘hearables’; hence medical company Sonova licenses Sennheiser’s consumer brand, and also Masimo, another medical company, turning Australia’s ‘nura’ earbuds into Denon’s PerLs.

Zildjian’s ‘Perfect Tune’ system uses an evolved version of the Audeara test; it takes perhaps five minutes, listening to bleeps coming and going at various frequencies to one ear then the other; you get a training session beforehand but it might make sense to do the whole thing twice, to ensure you have the hang of it and create a solid profile. This profile is stored in the app and you can then turn it on or off, alongside various EQ profile options.

With the separate EQ options all off, we started A-B listening between the ‘normal’ sound and our new ‘Perfect Tune’ (aka Audeara) profile. It’s hard to compare, because the Perfect Tune result was a few dB louder, so most people will pick it by preference anyway. After volume matching there was not much difference between the two, as we’ve often found with these systems, which we might hope indicates that our hearing is not too horribly askew and hence the app has had little effect. For those with more serious deficiencies, including those many drummers, the correction may be far valuable; we certainly have full respect for Audeara, its aims, and its Australian technology.

Listening sessions

Which left us to get down to some straightforward listening, though headphones being what they are (little speakers that may benefit from settling in), they were first left jacked into an amplifier and left playing for a night and a day. Then we paired them via Bluetooth to our iPad Pro, using Tidal to play tunes, and the Zildjian app to play initially with the sound options.

And in fact we reviewed these Alchem-Es twice over, because only after returning the first pair were we told by Zildjian HQ that those ones weren’t finalised. So we held the review back awaiting a production pair, and listened again. And it’s good we did, because the production run pretty much fixed the two issues we had noted.

That knob on the right headshell was one of these: in the original headphones it was not as smooth in its effect as Apple’s crown; there could be a slight delay to the notches of adjustment, and an infuriating and quite unnecessary ‘boom’ sound when you hit maximum volume (occasionally it would say 'eleven', in a Spinal Tap reference; this seems to have gone on the final version! More usefully, on the final headphone the knob worked more smoothly, and the ‘boom’ had gone, although when turning them up we did find they occasionally jumped a track instead; a couple of times they got stuck madly scrubbing forwards.

We did experiment with the ordinary EQ, the displayed curves for which look rather more radical than the usual offerings in such apps, and also worked rather better than most. But there were some oddities – selecting EQ at all dropped the level, and turning it off again didn’t raise it back! On the original pair this would have been a problem, as we were hitting maximum volume quite a lot when playing un-normalised recordings (not unusual with Bluetooth transmission), so any additional reduction can limit our enjoyment, as we do like to be able to listen loud.

We further note the inclusion of three options for ‘Volume Limiter’, labelled ‘generic (recommended)’, EU standard, and Kids Safe. Laudable of course, but there is no option to turn them all off, so we were unsure if maximum levels were being suppressed or not here. It’s good to have medical technology in headphones, but they’re neither your doctor nor your mother, and we’d prefer full control to turn things like this off, to see what happens. Pleasingly the manual does call the ‘generic’ an ‘Off’ setting, but the app doesn’t, so it’s not clear. On the whole we settled again for everything off, and avoided the EQ section.

The other main change to the second pair of headphones was their sound; the early pair did not particularly sparkle; they did not open a mix up wide like Apple’s overears, even the Sennheiser Momentum 4s. We thought them tonally more like Bowers & Wilkins headphones – in whose territory they are launching.

But our second pair, from a full production run, sounded more lively and open, an excellent longterm listen. Their bass was firm, sometimes very impressive with electronica that delved deep without being too strong, so it was kept clean. There was certainly no fear whether a bassline would fade as it fell to its lowest notes – it won’t.

The sound was also marginally clearer and better balanced when noise-cancelling was set to off; it had a small bloat and a tad more brashness when fully on, which could over-engorge very deep dub bass parts especially. The acoustic bass on GoGo Penguin’s Raven came through too thick; with noise-cancelling off we sought an EQ fix, trying jazz and classical, but never found an option that both tamed the bass and opened up the space available in this recording.

After quite a long listening session, we did wonder if things were just a little thumpy on some recordings, so that a cleaner sound might be even less fatiguing. We tried that personalisation again on the new pair, but again just made things a tad louder, and not much different.

In the final production pair, the ANC modes again proved powerful but, as described earlier, also unusual. The ‘100% on’ really was full-on cancellation, and even 50% was strong; both these modes brought a small level of eyeball suck (or eardrum pressure, as some call this effect).

Stranger, though, both 50% and ‘off’ seemed to include some ambient sound fed from outside; if we clicked our fingers around the headshells we could hear them at the tops of the earshells, where microphones were indeed found hiding behind the yokes. We can see no real purpose to this for hi-fi listeners, especially in 100% mode, so it must play to that specialised ANC which is tailored to dampening down kit sound for drummers.

This may also explain the lack of some other consumer functionality – no real ambience setting, no ‘smart pause’ when you remove the headphones, things that are commonplace on other headphones at this price.

What happens when wireless headphones run out of power? With most you can switch to cabled use (though not all, notably the Apples). A cable is equally useful when plugging into inflight entertainment, though Zildjian provides no airline plug adaptor. You do get a neat branded cable management disc, and when connected via cable you have two choices: play with power on, or off. With power off your device, a laptop say, controls the volume, you obviously have none of the EQ and personalisation available, and the sound was fairly soft.

Power the headphones up with the cable still connected, and you then have volume control via the headphone knob, also ANC available, and a whole lot more treble cut-through, brighter than the Bluetooth playback as well. But listening to the various balances, it seems clear that the Alchem-Es have been balanced primarily for Bluetooth listening, and sensibly so, since that will be their main usage.

Usefully, you can keep the app connected even when you’re listening to another source; we were able to Bluetooth from a laptop at the same time as adjusting EQ and other settings on a Bluetooth-connected iPad.

Verdict

We like almost everything about these headphones. We like that they’re big, we like the long battery life, the clear emphasis on both protecting and potentially correcting hearing, at a seemingly medical level. The sound is competitive at the price, powerful if not as wide open as some, though that’s judging against the best-regarded competitors – some pretty good cans.

And if you’re a drummer, of course, then this is clearly your headphone, made by people who care about you. That’s surely worth a closing ba-da-dum-tish.

Jez is the Editor of Sound+Image magazine, having inhabited that role since 2006, more or less a lustrum after departing his UK homeland to adopt an additional nationality under the more favourable climes and skies of Australia. Prior to his desertion he was Editor of the UK's Stuff magazine, and before that Editor of What Hi-Fi? magazine, and before that of the erstwhile Audiophile magazine and of Electronics Today International. He makes music as well as enjoying it, is alarmingly wedded to the notion that Led Zeppelin remains the highest point of rock'n'roll yet attained, though remains willing to assess modern pretenders. He lives in a modest shack on Sydney's Northern Beaches with his Canadian wife Deanna, a rescue greyhound called Jewels, and an assortment of changing wildlife under care. If you're seeking his articles by clicking this profile, you'll see far more of them by switching to the Australian version of WHF.