What Hi-Fi? Verdict

With stunningly minimal looks and exceptional performance, Yamaha's GT-5000 could be the turntable to rule them all. If you don't already have a tonearm of choice that you'd prefer to use, you're missing out by not picking yourself up this beauty.

Pros

- +

Superb performance

- +

Fabulous looks

Cons

- -

Plus-sized

- -

Fiddly tonearm adjustment

Why you can trust What Hi-Fi?

This review and test originally appeared in Australian Hi-Fi magazine, one of What Hi-Fi?’s sister titles from Down Under. Click here for more information about Australian Hi-Fi, including links to buy individual digital editions and details on how to subscribe.

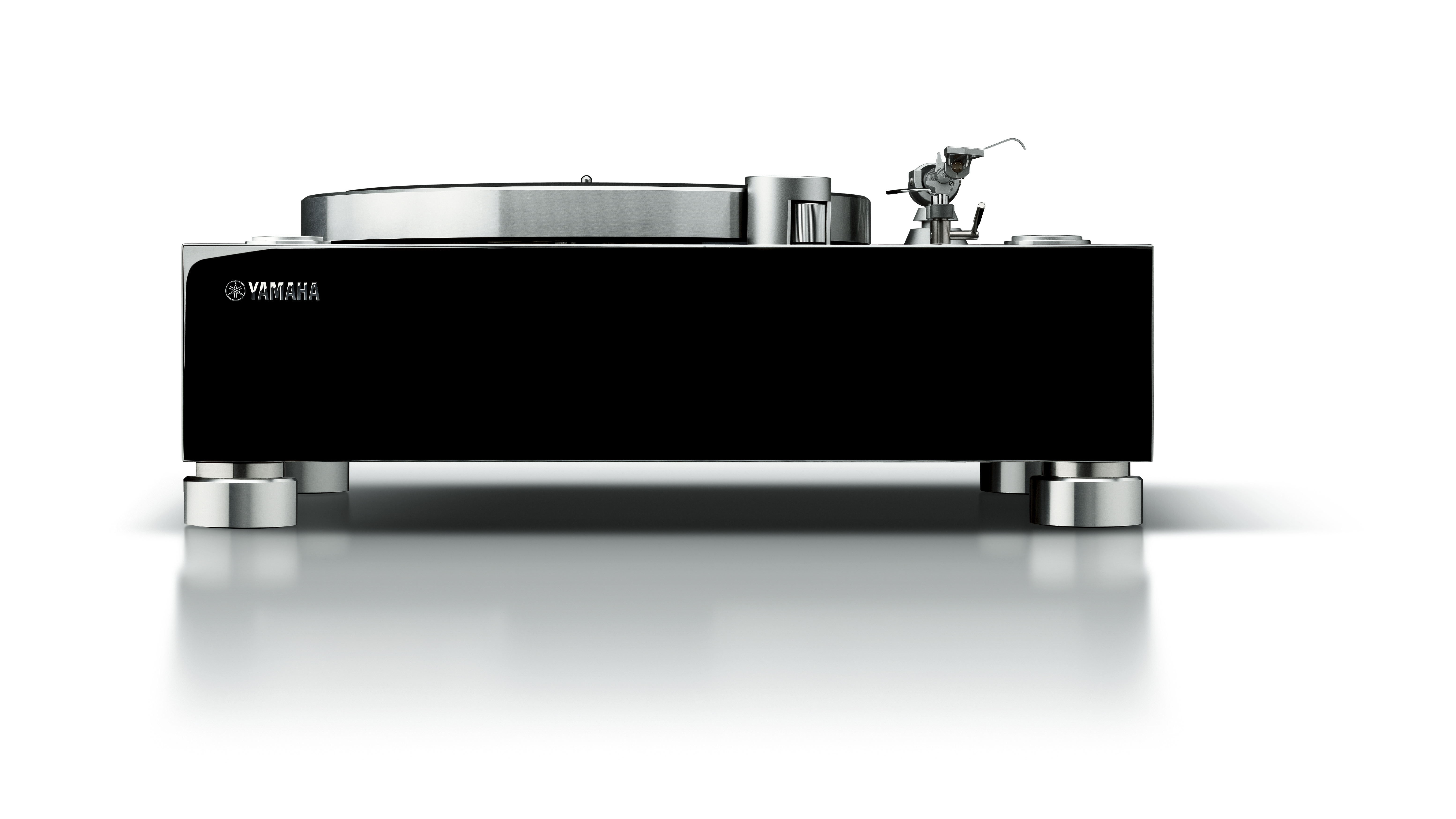

Don’t be fooled by any photographs you might see of it, including the one above. They all make the Yamaha GT-5000 look like it’s a standard-sized turntable. It’s not. Take the platter for a start. The platter on most turntables is 30cm in diameter. The platter on the GT-5000 is 35cm in diameter. That’s a big difference. So whereas the chassis of most turntables is around 42cm wide and 32cm deep, that of the GT-5000 is around 55cm wide and 40cm deep.

And then there’s the height. Let me tell you about the height.

The chassis itself is 12cm thick, to which you need to add another 4cm to account for the four support feet, then a further 8cm for the height of the tonearm. So, overall, that’s a total height of 24cm. And if you use the Perspex dust-cover, it just gets even higher!

So it’s big, but given the stonkingly good looks of the Yamaha GT-5000, you’ll probably be wishing Yamaha had made it even bigger!

It’s finished in high-gloss piano black and, given that Yamaha is the world’s leading manufacturer of pianos, that means it’s had plenty of experience with this particular finish, so as you’d imagine, the piano black gloss finish on the GT-5000 is absolutely superb. It’s mirror-like, with not even the smallest flaw to be seen in its almost mirror-like surface.

The superb piano black finish is made to look even better because of the contrast between it and the massively thick (35mm) silvered platter. The reflection in the black surface of the platter as it rotates is simply mesmerising.

Equipment

As with almost all turntables, some assembly is required, but with the GT-5000 it’s minimal, and doing it gives you the chance to appreciate the insanely high quality of all the component parts.

Once you’ve unboxed it (no small task in itself, given the GT-5000’s size and weight, so it’s definitely a two-person job) the first thing to do is fit the 2.025kg, 140mm diameter subplatter over the spindle. I’m not too sure what this subplatter is made of… maybe it’s bronze, or it may be brass, but it’s certainly heavy and it press-fits down over the slightly tapered lower section of the spindle so closely that I’d doubt you could fit a single atom between them.

It was the first of my many insights into the stupendously good machining of the GT-5000.

Then it’s time to attach the single, short (480mm) flat rubber belt firstly around the subplatter and then around the alloy drive pulley. The drive pulley is very slightly flexible, which suggested to me that the motor itself is isolastically isolated from the chassis. As with most vendors, Yamaha supplies white cotton gloves with the GT-5000, and you most certainly should be wearing these when fitting the subplatter and drive belt, to avoid oils from your skin from making the surface or the belt slippery.

The main silvery alloy platter is unusual, not simply because it’s so heavy (4.88kg), but also because of its diameter, which I’ve already mentioned, but additionally because of the unusual semi-circular ‘gutter’ that runs around its periphery. Once you have fitted the platter, a rubber mat virtually press-fits down over the entire surface, thanks to a matching ‘gutter’ moulded into it, which can be topped (or not, as you choose) with a final anti-static slip mat.

Although I don’t normally talk about disassembly in my reviews, because the only time you’d do this is if you’re moving house, I just have to mention it in this particular review because it highlights the superior engineering of the GT-5000. Firstly, the fit between the rubber mat and the platter is so glove-like that you’ll be hard-pressed to remove it. That’s amazing for a moulded product. As for removing the main platter from the spindle, well it’s so close to the surface of the turntable that you can’t really get your fingers under it, and the fit around the spindle is so tight (and gets tighter the longer you use the turntable) that Yamaha provides two lifting handles that screw into the platter in order that it can be removed.

As I hope I’ve made perfectly clear, the precision of the machining and moulding on the Yamaha GT-5000 is incredibly good. You can really see/feel the difference between turntable manufacturers that just “do it themselves” using off-the-shelf machinery or get a local engineering firm to just “do it for them” and a company like Yamaha, which is obviously using state-of-the-art equipment to achieve what I imagine to be sub-micron tolerances.

You’ll be able to admire the engineering even if you’re looking at a Yamaha GT-5000 turntable that’s already been assembled. All you have to do is get the platter rotating at 33.33 rpm (or 45 rpm, if you prefer) then crouch down and get an eye-line across the periphery of the platter at a spot on a wall behind. You will immediately see that there’s absolutely no vertical motion at all… it will be as if the platter were stationary.

If you do this same check with any other turntable, I’m pretty sure you’ll see a tiny up/down motion as the platter rotates, showing that it is not rotating evenly. The Yamaha GT-5000’s rotation is dead flat. Amazing! And if you look at the edge during rotation, using the same eye-line trick (or even a laser, if you want to go high-tech, like I did) you’ll see there’s no rotational eccentricity either, which is even more amazing.

The GT-5000 comes with its own custom, straight arm-tube tonearm already installed, but you will have to firstly install a cartridge and then adjust the height of the tonearm to establish the correct vertical tracking angle (VTA) for the particular phono cartridge you’re using. You’ll also have to set tracking force, but this is via the completely conventional method of having a threaded counterweight. Yamaha actually provides two counterweights of different mass, which you select according to the mass of your particular phono cartridge.

Tonearm height is adjusted by loosening a hex head screw on the side of the tonearm post, after which the post slides up and down. I found making this adjustment quite tricky, because the tolerances are so fine that it’s difficult to accurately move the post up and down by sub-millimetre increments, particularly since it has to be done by hand: there’s no mechanical adjustment system.

Because of this, I’d recommend buying a really, really, cheap cartridge with the same dimensions as the one you intend to use, along with an after-market head-shell, and fitting this while making the adjustment. I’d also recommend doing it while using an LP you don’t play so that if there’s any mishap of some kind, there will be no chance of damaging a stylus or an LP or both, because it’s very hard to get micrometer-like precision on the arm height when you’re reduced to doing it by hand.

If all this seems a bit complex, another method I thought up would be to work out how high the ‘collar’ of the tonearm post needs to be above the base, then make a shim that’s exactly this height and then raise the tonearm post and lower it down on the shim, after which you could then tighten the hex-head screw. Given the almost unbelievably high level of engineering expertise that’s gone into the rest of the turntable, I was rather puzzled that an equal level did not seem to have been applied to the tonearm height adjustment methodology.

Yamaha has gone out on a limb with the design of its tonearm, because it has a shorter effective length than most other tonearms, and lacks an offset angle, which means that its arc across the grooved area is more pronounced than would be the case if it were longer. Also there is no anti-skating device fitted. I thought I should ask Yamaha about its rationale for the tonearm length and the lack of anti-skating, and received a reply from no less a personage than Kiyohiko Goto, Chief Engineer at Yamaha Japan’s AV Division.

Regarding the tracking error he says: “A short straight arm has excellent tracking performance because the inside force is generated at the point of contact between a stylus tip and groove of vinyl and is always variable with the variate of the music groove. In the case of a short straight arm, its null point (= balanced point) is at the middle of the grooved area (so) the maximum tracking error is 10 degrees at innermost and outermost grooves. The distortion caused by this small error angle is inaudible because it is lower than both the tracing distortion and the residual noise. Furthermore, tracking error appears as phase shift between the left and right channels, and even at its maximum (10 degree) error the phase shift that results would be the same as caused by a difference in the distance from the left and right speakers to the listener of only 2mm. This also does not cause any problem for sound.”

As for the lack of anti-skating, he says: “A short straight arm does not require anti-skating because [at maximum error angle] if the vertical tracking force is 2g, the frictional coefficient is 0.3, and so the inside force (outside force) will be approx. 0.1g. In the case of a conventional offset arm with a maximum tracking error of 2 degrees, the inside force will be approx. 0.02g so the difference of the max inside force between a short arm and an offset type will be 0.08g at the maximum, thus the difference in force is very small.”

“On the other hand, when anti-skating is employed, because it applies a constant force it never cancels the inside force which constantly changes as its follows the music signal. The constant differences between the variable inside force at the stylus tip and the constant force by the anti-skating adversely affects the cantilever, hence the tracking performance is not stable. In a short straight arm the tracking performance following (the) music groove is excellent because the variable difference of force between the stylus tip and tonearm (cartridge) is not generated.”

Whatever you think of Yamaha’s approach to tonearm tracking/tracing (and I should point out that in the previous paragraphs that I have paraphrased a translation of Kiyohiko Goto’s original Japanese-language explanation, so any errors are mine alone), the practical result is that you cannot use a conventional Baerwald, Stevenson or Loefgren cartridge alignment tool to align your cartridge in the tonearm.

You instead have to use the alignment tool Yamaha supplies with the GT-5000.

Yamaha’s alignment tool comes in the form of a black metal disc that slides down over the spindle and has the necessary cartridge calibration marks scribed in it. This disc also doubles as a speed calibration device, by virtue of the strobe marks inscribed on it… though you’d be hard-pressed to instantly recognise these as strobe markings because rather than provide them in the form of straight lines, as with most other strobe ‘cards’ I’ve ever seen, Yamaha has instead provided the markings in an ‘arrow’ formation.

I initially thought these arrows were bit of a gimmick, but when I compared Yamaha’s strobe with my own (which has straight lines) Yamaha’s strobe was was actually the easier one of the two to use, and also the most accurate. Yamaha’s strobe lines also look better, but that’s probably by-the-by.

Interestingly, there were only two strobe rings (one for 33.33 rpm and the other for 45rpm) on the calibration disc, which means that Yamaha must be supplying completely different calibration rings depending on whether the turntable will be used in a country with a 50Hz mains frequency (Australia and the UK, for example) or in a country where the mains frequency is 60Hz (such as the USA or Japan).

As for the strobe light that’s necessary for the strobe card to work, any fluorescent light will suffice for this purpose, but on the off-chance that you don’t have one handy, Yamaha provides a small strobe light with the GT-5000. It’s at the end of a piece of flexible cable that plugs into a power supply at the back of the turntable.

So what does the post at the front of the GT-5000 do if it’s not a strobe post? That’s where you adjust the speed of the platter. This means that you have to hold the strobe light with one hand while you use the other hand to adjust platter speed. I have to say that while this is a perfectly practical way to do this, it felt a little ‘odd’ and just a bit ‘Heath Robinson’. I wish Yamaha had thought of another way to implement this.

Speed change is achieved by pressing the small button behind the large Start/Stop button at the right side of the turntable plinth.

When you change speed by pressing it down and releasing it, the relevant (33 or 45) LED blinks green twice very brightly then glows steadily at reduced brightness. When the switch is at 33, it sits exactly flush with the bezel around it, whereas when it’s at 45 the top of the switch sits 2.5mm proud of the bezel.

The same physical action is true for the platter Start/Stop button and the Power button (at the left of the plinth). When the Start/Stop button is in ‘Start’ mode, the button is flush with the bezel, and when it’s in ‘Stop’ mode, it sits proud of it. And when the power button is set to ‘On’, the button is flush with the bezel, whereas when it’s off, it sits proud of it. This is not only elegant engineering, it also means you can instantly tell the status of the control even when your eyes are closed, or in complete darkness.

Around the rear of the GT-5000 you’ll find something completely surprising, which is that it has not only a pair of standard unbalanced RCA outputs (gold-plated of course), but also a pair of balanced XLR outputs (also gold-plated). Even the essential ground terminal screw is gold-plated. All these are located on one mounting plate at the left of the turntable. At the right is another plate that has a standard 3-pin mains socket and a smaller, 3.5mm socket for the strobe light.

Also on the rear are four chromed knurled screws, in two pairs. These are to attach the heavy-duty clear perspex dust cover that in many countries is apparently an optional extra but here in Australia comes standard with each turntable, but packaged separately, so that owners can choose to fit it or not.

Listening sessions

Yamaha does not supply a phono cartridge with the GT-5000 and, so far as I could ascertain, does not supply a list of cartridges that might be suitable for it. When I say ‘suitable’ I intend this to mean a list of phono cartridges which can be installed in it such that their stylus is able to be correctly calibrated according to Yamaha’s gauge.

I mention this because several of my cartridges had their stylus so far back in the cartridge body that I could not get the stylus to the alignment point on Yamaha’s gauge even when the mounting holes at the top of the cartridge were at the extreme end of the adjustment slots on Yamaha’s head-shell.

As a professional hi-fi reviewer I was in the enviable position of having many different cartridges on-hand, and was fairly easily able to find several that I was able to align as per Yamaha’s instructions.

I also had quite a few different head-shells available, several of which allowed a greater range of adjustment than the one Yamaha supplies, which then allowed me to use the ‘shorter’ cartridges. In the absence of a list from Yamaha, you will need to depend on your hi-fi retailer’s knowledge with regards to phono cartridge suitability.

My ability to fit alternative head-shells was made possible because Yamaha’s tonearm has a standard ‘universal’ head-shell fitting.

The very first thing I had to do after cartridge alignment was to use the strobe to ensure the platter was rotating at exactly 33.33 rpm. Having not done this initially, I found it a bit difficult to locate the strobe cord’s plug in the socket at the rear, so you should bear this difficulty in mind if you’re planning on regularly inserting and removing the strobe light… and I certainly wouldn’t recommend leaving it switched on permanently.

In point of fact, the only reason I can think of that you’d have to regularly insert and remove the strobe light is if you regularly play 45 rpm LPs, because I found that if I set the speed to 33.33 rpm using the strobe, then switched to 45 rpm, the strobe showed that the platter was running slightly slow, which meant tweaking the platter speed up a little. If I then switched back to 33.33 rpm, the platter ran slightly fast, which meant another platter speed tweak.

But any constant speed adjustments using the strobe would assume, of course, that you actually want the platter to be rotating at exactly 33.33 rpm or at 45 rpm and there’s really very little reason you would actually want to do this. The simple fact is that a great many LPs need to be run slightly off-speed if you want the music that’s contained on them to be true to the pitch at which the music was originally played.

This comes about because of the limited playing time available on an LP meant a work that was played and recorded at the right pitch (i.e. A=440Hz) would often be too long to fit onto the two sides of an LP. Recording engineers would then ‘solve’ this problem by speeding up the tape recorder feeding the cutting lathe, which then reduced the duration of the work so that it would fit.

However, speeding up the recorder in this way also raised the pitch of all the instruments (and voices), so that if the turntable used to play the LP was set for 33.33 rpm (the so-called ‘correct’ speed) the pitch of those instruments and voices would be higher than it should be. Being able to set the platter to rotate slightly slower than 33.33 rpm (via a pitch control) allows corrections for such pitch inaccuracies.

Another situation where you might not want a turntable to play at exactly 33.33 rpm is when you want to play along with an LP with a notionally fixed-pitch instrument, such as a piano, and you find that, for whatever reason, your piano is slightly out of tune with the LP. A little tweak on the pitch control (either up or down, as appropriate) will have you playing along in perfect harmony. And if you sing along, and can’t quite reach the very highest notes (or the very deepest) an appropriate touch on the pitch control will fix both these issues as well.

Call me slow to twig, but I had not realised why there was a groove at the periphery of the GT-5000’s platter until it came time to actually place my very first LP onto the platter, at which point it suddenly dawned on me that because the Yamaha’s platter was ‘way bigger than the LP, the groove was essential in order to allow LPs to be easily positioned and removed.

Which got me to thinking why the platter was so much larger than usual in any case, and another light in my brain went on: Inertia, or probably (I forget the physics and didn’t google it), Moment. Basically, the larger the diameter of any wheel (platter), the greater the ‘flywheel’ effect, and thus the greater the stability of rotation.

Clever, very clever! (And here I’m not talking about me, but about Yamaha’s engineers.)

The large, heavy platter has one slight drawback, which is that it’s a bit difficult for the single flat drive-belt to coax it up to speed. I discovered that every time I pressed the play button, there was initially a tiny bit of slippage, after which it took 15 seconds for the platter to stabilise at 33.33 rpm. And if you press the play button again to stop the platter, it takes a full 23 seconds for the platter to come to a complete halt.

It won’t come as a surprise to regular readers to find that that very first LP I placed on the Yamaha GT-5000’s platter was my new favourite recording of Eric Satie’s Gymnopédies as performed by Anne Queffélec (Virgin Classics 522 0502) whose tempi are perfect and whose rubato is glorious. I just love the liberties she takes with the score, which elevates it from just being ‘another virtuoso performance’ into another league completely. (Though as another reviewer was insistent I point out, she was not brave enough to omit the final chord.)

The reason for playing Satie was, of course, that slow (very slow, insanely slow) piano music will immediately reveal if a turntable’s platter is ‘wowing’ (slow speed variations) or ‘fluttering’ (higher speed variations) as it rotates. I can happily report that I heard zero wow and zero flutter when auditioning the GT-5000. I also did not hear any cogging effects which, of course, is precisely the reason Yamaha elected to use a belt drive rather than a direct drive for its GT-5000 in the first place.

In the words of Yamaha’s Kiyohiko Goto: “A belt drive has been adopted to minimise the effects of uneven rotation due to motor cogging. Feedback used for direct-drive control cannot fundamentally eliminate the response time regarding rotation unevenness caused by cogging, and this affects the sound. To avoid this, a motor drive that does not require feedback technology has been adopted.“

Cogging is a strange phenomenon, but it’s certainly audible, and the GT-5000 obviously doesn’t have it. But in a world of superior belt-drive designs, the GT-5000 to me stood out as being even more superior, because the sound was just so smoooth (and I stand by the extra “o” in that word, because the sound from the Yamaha GT-5000 is actually smoother than smooth, but I just didn’t have a word to describe it). There was a beautiful ease and ‘flow’ to all the music I played on the GT-5000 that transported me to a higher plane.

Having been a bit concerned about the tracing ability of a shortish arm and the lack of anti-skating, I put the combo to the test with a couple of my favourite albums only to find that it absolutely sailed through Emerson Lake and Palmer’s first and second albums (they being Emerson Lake and Palmer and Tarkus) both of which are notable for possessing far more bass energy than most ordinary phono cartridges (and tonearms) can handle and therefore are very difficult to track. (Though not as difficult as the cannon-fire in Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture with Erich Kunzel and the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra on Telarc, which the GT-5000 also sailed through with flying colours. )

ELP is a tour-de-force of an album, not least because of the individual musicianship of the band members – particularly Emerson – but also because two of the tracks (Barbarian and Knife Edge) were partly written by those three famous rock musicians Béla Bartók, Leoš Janáček and Johann Sebastian Bach.

(For confused readers, Barbarian is a reworking of Bartók’s Allegro Barbaro – from whence the name – and Knife Edge sounds a lot like a melding of the first movement of Janáček’s Sinfonietta with the Allemande from Bach’s French Suite in D minor, BWV 812.)

If you’re at all surprised by this revelation, you shouldn’t be. Many of the greatest rock classics of recent times are just knock-offs from the great classical composers. One of Billy Joel’s most famous compositions is almost a transcription of a well-known classical piece, indeed I very recently saw a TV interview where when Paul Simon was being praised for a particular tune that bore his name he quite happily admitted that it wasn’t his, and played the original, classical version on the guitar he just happened to have in his lap to prove the point. And just in case you were wondering, it’s all perfectly legal and legit. The copyrights lapsed a few hundred years ago, and you don’t even have to credit the original composer.

When it was pointed out that what is possibly Procol Harem’s most famous song (A Whiter Shade of Pale) was a Bach knock-off, with even Wikipedia coyly noting that: “The similarity between the Hammond organ line of A Whiter Shade of Pale and J.S. Bach’s Air from his Orchestral Suite No. 3 BWV1068, (the Air on the G string), where the sustained opening note of the main melodic line flowers into a free-flowing melody against a descending bass line, has been noted.” Gary Brooker, who is credited with the composition (and still owns the copyright!) told Uncut magazine: “I wasn’t consciously combining rock with classical, it’s just that Bach’s music was in me.”

Just to be fair and even-handed, all the greatest classical composers also “knocked off” tunes from other composers, as well as blatantly recycled their own best themes and melodies into other of their compositions, but back then, copyright wasn’t a thing, and due to a lack of recording/playback facilities, any liberties taken by composers who knocked off others’ compositions were unlikely to be discovered.

Rumble, signal-to-noise ratio… call it what you will, you don’t want any in a turntable and you certainly won’t find (hear) it issuing from Yamaha’s GT-5000. This is one silent turntable. Super silent. I eventually gave up trying to hear any rumble or bearing noise when listening to music and instead resorted to using a stethoscope borrowed from my brother-in-law to listen to the plinth in a dead-quiet room. While I could hear some noise at the ‘motor’ (left) side of the plinth, I could hear nothing at all at the all-important (tonearm/right) side of the plinth.

Verdict

Yamaha’s GT-5000 is such a mind-blowingly fantastic turntable that the only way I think it could be improved is for Yamaha to offer a version without a tonearm. Admittedly such a model would most likely appeal only to those audiophiles who already own a favourite tonearm, such as ‘The Wand’ from Simon Brown, or a Sorane ZA-12, or maybe even a classic such as an SME Series V, but I think there’s a fair few of them around, and given the level of performance of the GT-5000, they’d be absolutely queuing to buy one!

But if you don’t already own a favourite tonearm, then you have absolutely no excuse not to buy a Yamaha GT-5000: it’s just that good!

Lab test results

The absolute speed accuracy of the Yamaha GT-5000 will be down to how accurately the user can set the speed using the strobe light and disc, because there is no ‘default’ or ‘0’ setting on the pitch control knob, so Newport Test Labs instead used a test record with a 3kHz test tone and set the speed using a frequency counter to ensure the most accurate measurements.

Once the GT-5000’s speed was set to exactly 33.33 rpm, the lab switched the platter speed to 45 rpm and played a 3kHz test tone that had been recorded at 45 rpm. The frequency counter reported the frequency as 2990Hz, 10Hz lower than it should have been. This is only 0.3% low, and not much in terms of absolute pitch so you may not want to bother about adjusting it, but of course it’s easy enough to do if you do care.

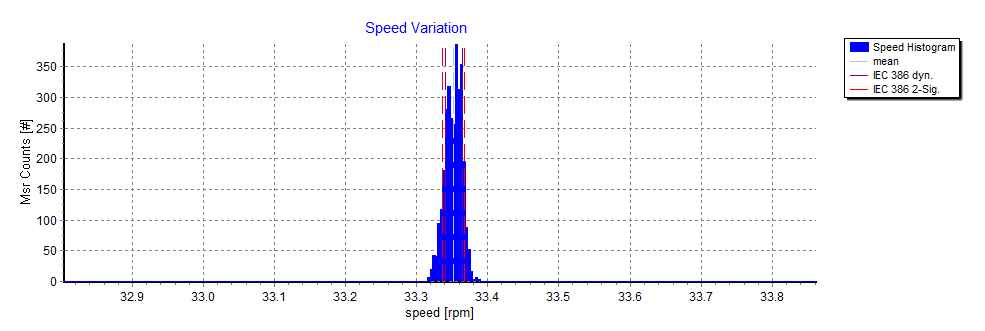

Long-term speed variations were vanishingly small, as you can see from the histogram below.

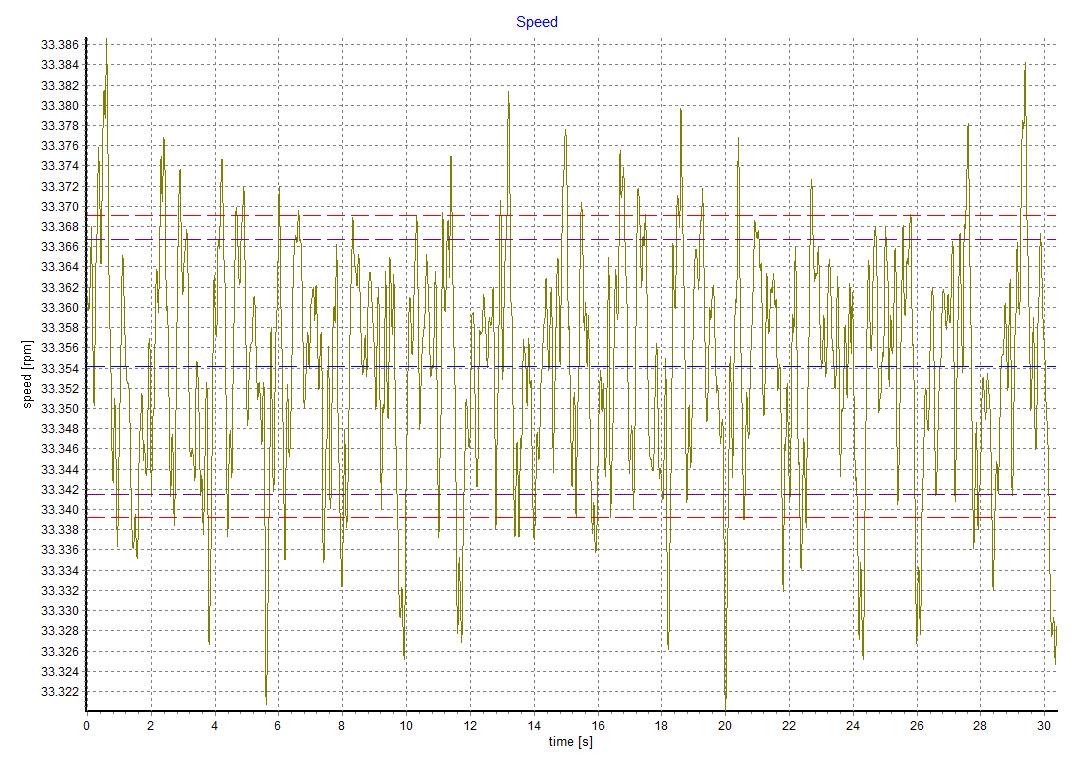

Rotational stability, as measured by Newport Test Labs, and as shown in Graph 2 (below), was also excellent. This test measures the speed for a full 30 seconds. The raw variations are shown by the khaki coloured trace. The mean speed over the period is indicated by the dashed blue line. The overall wow and flutter, measured according to the IEC 386 standard is shown for a dynamic measurement (purple trace) and for a 2-Sigma analysis (red trace).

Newport Test Labs used separate Meguro and MTE instrumentation to measure long-term (20-minute) speed variations and reported wow and flutter as being 0.06% RMS unweighted and 0.08% CCIR weighted. The wow and flutter the laboratory measured was identical for both 33.33rpm and 45rpm speeds, for both the RMS and CCIR standards.

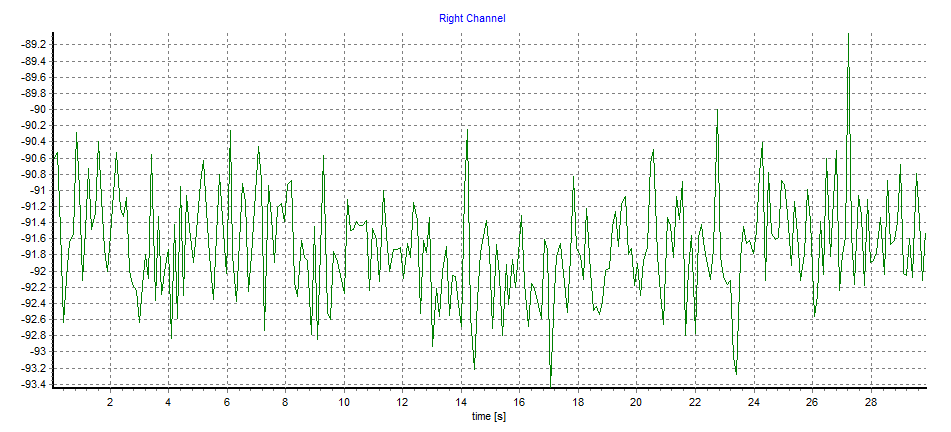

Graph 3 shows the noise (rumble) of the Yamaha GT-5000, referenced to a 315Hz test signal recorded at a velocity of 3.52cm/sec. You can see that it’s mostly more than 90dB down, which is an outstandingly good result: the best I have ever seen, in fact.

The Yamaha GT-5000’s power consumption is negligible, with the turntable drawing only 0.41 watts (+0.845 PF) in standby, and only 10.67-watts (+0.755PF) at 33.33rpm.

On the basis of these outstandingly good test results I can confidently state that the Yamaha GT-5000 sets a new standard in turntable performance.

Australian Hi-Fi is one of What Hi-Fi?’s sister titles from Down Under and Australia’s longest-running and most successful hi-fi magazines, having been in continuous publication since 1969. Now edited by What Hi-Fi?'s Becky Roberts, every issue is packed with authoritative reviews of hi-fi equipment ranging from portables to state-of-the-art audiophile systems (and everything in between), information on new product launches, and ‘how-to’ articles to help you get the best quality sound for your home. Click here for more information about Australian Hi-Fi, including links to buy individual digital editions and details on how best to subscribe.