Sound+Image Verdict

Lesser projectors offering Ultra High Definition deliver the required pixel count by pixel-shifting panels of lower resolution. Sony’s VPL-VW790ES is native up to full 4K, and it’s the best picture we’ve ever seen.

Pros

- +

Brilliant Ultra-HD performance

- +

Super longlife light source

- +

Easy setup

Cons

- -

Motion smoothing could improve

- -

Won't accept 576i/50 or 480i/60

Why you can trust What Hi-Fi?

This review originally appeared in Sound+Image magazine, one of What Hi-Fi?’s Australian sister publications. Click here for more information on Sound+Image, including digital editions and details on how you can subscribe.

This is a bit weird. We are going to briefly laud the maximum resolution of the new Sony VPL-VW790ES home theatre projector. And then we’re going to ignore it. What we’re really going to focus on is how well the Sony VW790ES projector works with content of slightly less than its full resolution.

Equipment

First, an oddity about the home projection market. While we live in a UHD world, where 4K Blu-rays, Netflix, Disney+ et al can deliver a resolution of 3840 × 2160 pixels, there are presently, to our knowledge, no projectors on the market which have a native resolution actually matching that.

Most UHD projectors use a chip of 1920x1080 pixels, shifting these to create additional pixels... with various degrees of success. Whereas this Sony VPL-790ES is even better than the real thing, its native resolution being actually a little higher than UHD, at 4096 × 2160 pixels. That is, it is a true 4K projector.

But of course it can act as a native Ultra-HD projector. It has display modes that simply crop off the unnecessary pixels to the left and right, making it act as native 3840 × 2160. That’s how we expect most people will use it. Unless they choose to use its anamorphic support for constant image height display, in which case having the extra pixels to left and right is all to the good.

The Sony VPL-VW790ES is one large projector – around half a metre on two dimensions and over 200mm tall. And it weighs 20kg. It is the premium consumer model from Sony short of the forthcoming “beast” of the VPL-GTZ380, its price expected to top AU$50k.

The VW790ES uses Sony’s SXRD – Silicon X-tal Reflective Display – a form of reflective silicon. And it uses Sony’s Z-Phosphor light engine, which uses a laser diode to stimulate phosphor into producing white light. The advantages of this over conventional lamps are long life, quoted at 20,000 hours, and the ability to rapidly adjust brightness.

Sony rates the brightness at 2000 lumens and says that the projector has an infinite ‘dynamic’ contrast ratio. To achieve that it employs both an active iris and adjustment to the light source output to maximise picture quality. The projector also supports 3D, though you’ll need to purchase the optional active eyewear. They sync via RF so they should work reliably.

Performance

We found only one problem when installing the projector, which was holding up the considerable weight while we affixed it to our ceiling mount! That done, it was easily optimised thanks to horizontal and vertical lens shift, a huge zoom range of 2.06:1 and powered controls for all lens adjustments. We could stand right up close to the screen and adjust all our settings just so.

Speaking of the remote, we appreciated that it had lots of keys. In addition to the usual things, we could switch directly to different picture modes by just tapping a key, and cycle through the different Motionflow settings along with lots of other picture settings.

First impression: the picture was brilliant. It was bright, colour was strong, blacks were very good. Continuing impression: the same. Let’s drill in a little.

We did most of our watching using the cinema modes, but one very interesting picture mode was called ‘Reference’. It didn’t take long to work out what was different about this mode: much of the content was ‘posterised’. That is, in areas where there were slow colour gradients, rather than subtle shifts from shade to shade, whole areas would be one colour, others would be distinctly different colours, with the borders clearly visible.

Sort of like a paint-by-numbers picture. This is what you see with an eight-bit colour depth and a display that isn’t papering over things. When we switched to any one of the other modes, all that went away and colour graduations were smooth. So the ‘Reference’ mode is for showing the source with utter accuracy, for good or ill. You may not want to watch much of anything in this mode, but it’s nice (especially for geeks) to have it there if you’re curious about what’s actually in the original signal.

When we went to check the quality of the projector’s progressive-scan conversion, we ran into a problem. It simply will not accept a 576i/50 or 480i/60 signal. ‘Out of range’ it says. It probably won’t matter much these days, as most source gear will do competent enough deinterlacing of SD content – though it may prevent you using settings which allow units to follow the source quality rather than delivering a fixed output. An interesting design decision.

What was certainly impressive was how well the scaling worked with 576p content. Remember, here the projector is turning frames of 400-ish thousand pixels into frames of 8-ish million pixels. (The factor is precisely 20x). Edges were surprisingly sharp; detail was preserved with minimal distortion.

The only two adjustments needed were changing the aspect ratio to widescreen – it defaulted to good old-fashioned 4:3 with 576p input – and keeping well away from the cinema picture modes. Those have the compression noise turned down to zero... but a lot of SD content is fairly thick with noise. We found that the TV mode worked well, or we could just turn up the noise reduction even in the cinema mode.

The progressive-scan conversion with 1080i/50 content was good enough. It was tricked only in the most difficult section, which trips up at least nine out of ten auto circuits. There is a ‘Film Mode’ control, but it only offers choices of ‘Auto’ or ‘Off’.

There are three settings for the Motionflow motion smoothing system. As usual, we went to Chapter 21 of The Fugitive to check out the Chicago flyover. Without any motion smoothing, the judder on this scene is appalling on a big home cinema screen. (We remain surprised that this scene was even used in the movie, given the obvious problems with it.) The three settings on offer were ‘Smooth High’, ‘Smooth Low’ and ‘True Cinema’. We have no idea what True Cinema does, if anything. We could see no difference between it and having Motionflow off.

‘Smooth Low’ seemed to insert one frame between each film frame. There was still judder but far less. This produced no visible heat-haze distortion, but it did make rivets on a railway bridge jump into the wrong place briefly. On this scene, soon after the flyover, the camera is panning to the left along the bridge while a train atop the bridge is travelling to the right.

We suppose that all this complexity briefly confused the motion processor. ‘Smooth High’ provided a very smooth flyover, yet still delivered the picture with the appropriate amount of grain for this 1993 film. But the moving rivets problem was worse in this mode.

Of course, the best way to enjoy super-smooth motion without distortion is to use one of the very few high frame rate discs out there. We used this projector to watch for the first time Ang Lee’s Gemini Man, a so-so sci-fi action thriller starring Will Smith. This was shot at 120 frames per second, and is presented on the Ultra-HD Blu-ray disc at 60 frames per second.

On this projector, it wasn’t merely smooth, it was stunning. And not just in the smooth motion, but in the way it truly realised the potential of picture sharpness. The detail somehow unleashed by the high frame rate would be very good on any decent Ultra-HD display. But on the large picture created by the true Ultra-HD engine of this projector, it was simply astonishing.

(We seriously suggest buying this UHD Blu-ray and finding a dealer with this projector set up for demonstration, and ask to see it. You’ll be seeing what we hope is the future of home entertainment.)

On regular 4K Blu-ray – that is, UHD Blu-ray discs at the usual 24fps – the results were also very impressive, if not quite as stunning as the HFR material. Colours were superbly natural and black levels were among the best we’ve experienced from a projector. And that’s with the lamp on full brightness.

You can adjust the lamp level on a continuous scale down to around 50%, so you can balance brightness and black levels to match your environment. While fairly quiet even at full brightness – we had the projector installed directly over our heads and never noticed the sound – the fan noise became the merest whisper at that low power output.

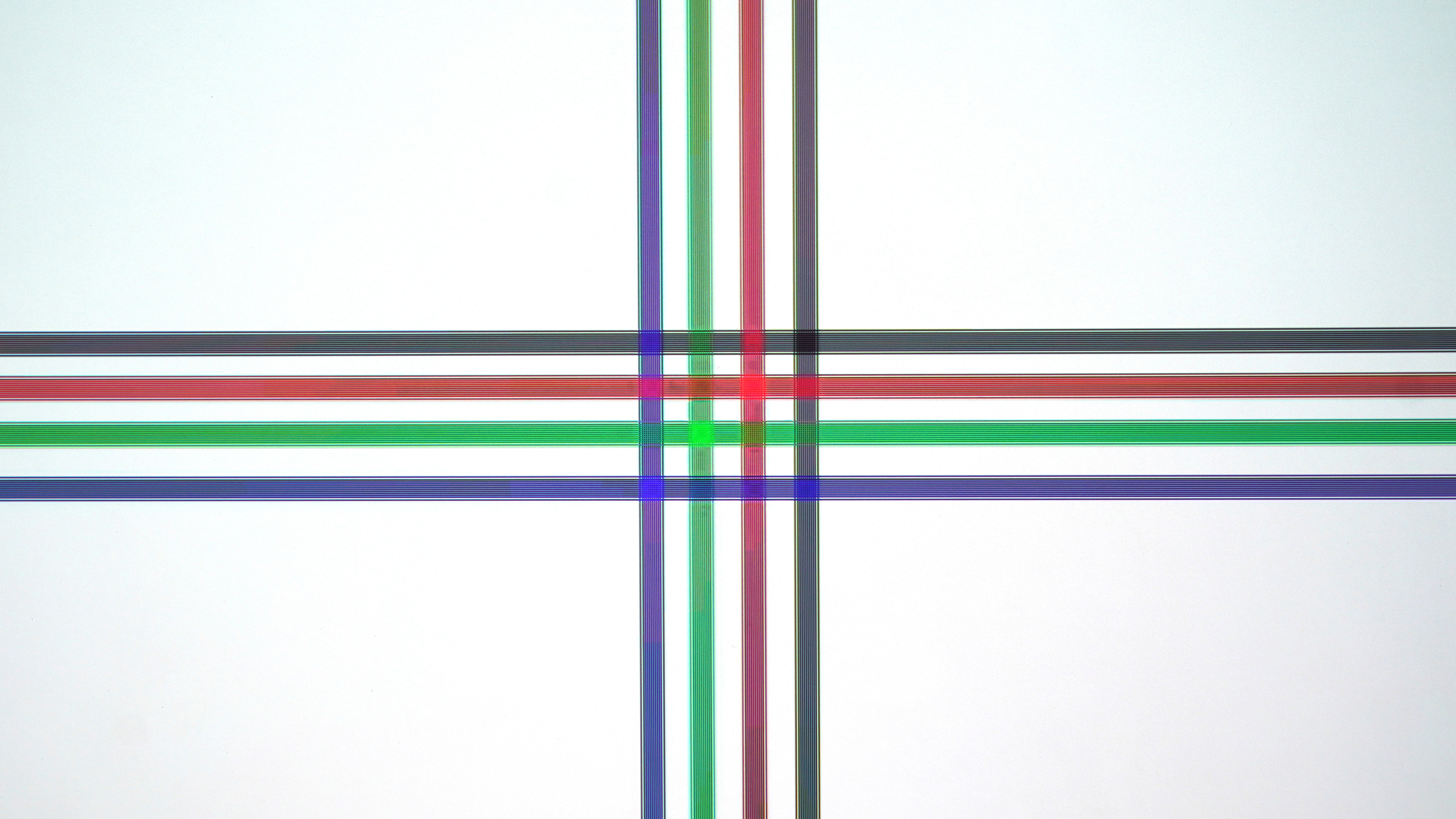

We can’t finish without mentioning actual delivered resolution. We used our standard UHD test pattern (reproduced photographically above) and, sure enough, the Sony VPL-VW790ES projector etched out each individual line with a discrete clarity beyond the best of the pixel-shifting wannabees, and more, the richness of colour in those individual pixel-width lines was markedly greater than we’ve seen with any pixel-shifting projector.

Not, we should add, that the lines were quite as clear as from a direct-view UHD TV, but not too far off either. There did seem to be some blooming where the same colours overlapped. We think that was the projector feeling it had to emphasise those – even though in the actual test pattern the intersections are no brighter than the lines themselves. In the time available, we couldn’t find a setting to get rid of that.

Final verdict

In short, the Sony VPL-VW790ES projector produces by a clear margin the best home theatre projector picture that we’ve experienced – and we mean ever.

Sound+Image is Australia's no.1 mag for audio & AV – sister magazine to Australian Hi-Fi and to the UK's What Hi-Fi?, and bestower of the annual Sound+Image Awards, which since 1989 have recognised the year's best hi-fi and home cinema products and installations. While Sound+Image lives here online as part of our group, our true nature is best revealed in the print magazines and digital issues, which curate unique collections of content each issue under the Editorship of Jez Ford, in a celebration of the joys that real hi-fi and high-quality AV can bring. Enjoy essential reviews of the most exciting new gear, features on Australia's best home cinemas, advice on how to find your sound, and our full Buying Guide based on all our current and past award-winners, all wrapped up with the latest news and editorial ponderings. Click here for more information about Sound+Image, including links to buy individual digital editions and details on how best to subscribe.