Sound+Image Verdict

While there are certainly some vinyls that are simply too far gone, for the most part the affordably-priced Record Doctor VI can recover the quality of your favourite LPs and singles, removing dust and other sources of crackle and pop.

Pros

- +

Audibly effective on most discs cleaned

- +

Easy system to use

- +

Discs emerge dry and ready

Cons

- -

Can't resurrect worse discs

- -

Noisy suction system

Why you can trust What Hi-Fi?

This review originally appeared in Sound+Image magazine, one of What Hi-Fi?’s Australian sister publications. Click here for more information on Sound+Image, including details on how you can subscribe.

Vinyl is a source with a difference – the software requires care. Cleaning is essential even with new discs, and if you’re out gathering bargains at secondhand record fairs, then a good cleaning system can transform a $2 purchase from a crackly listen into something more soothing. The Record Doctor VI is one such system which aims to reduce signal noise in your system by physically removing dirt from your vinyl.

Equipment

Record cleaners range from cheap-and-cheerful simple wiping solutions to ultrasonics and wildly expensive transcription systems of deep cleansing; we’ve covered many approaches in past issues.

The ‘Record Doctor’ inhabits a helpful zone where the price is not frightening at $299 (AU$485, with UK pricing and availability yet to be announced), yet the product is highly regarded and long established, as evinced by this latest ‘VI’ version being also the company’s 20th anniversary edition.

The Record Doctor cleans records using a suction tube surrounded by felt cleaning strips. You put the record onto a spindle to one side of the tube, and pop a large manual turning knob over the label of the record.

Then you dribble the supplied cleaning solution across the width of the vinyl, and hold a wide fluid-application brush to the surface as you rotate the disc once (or more) until the whole disc becomes coated with the fluid.

Next, flip the disc so the wet side is downwards and replace the turning knob, switch on the suction pump, and rotate the disc until the vacuum has sucked the underside dry. Repeat for the other side, and your LP is clean and ready to play or store.

Such has been the way of the Record Doctor since it was introduced 20 years ago. The latest version has various upgrades and updates, which include a larger turning knob which now fully covers the record label, also a new deeper-cleaning spreading brush for the fluid stage, and a better overall finish including a stain-resistant aluminium top (presumably previous versions were becoming marked by fluid dripping from over-lubricated undersides). A black dust cover, similar to an inverted reusable shopping bag, is another useful addition for the VI edition.

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

Operation

It’s ironic that a product designed ultimately to reduce noise levels should increase them so significantly during its operation. One of the upgrades advertised for the ‘VI’ version is that it runs “cooler and quieter” than its predecessors – but the suction system nevertheless makes quite the hum.

With a simple bathe-and-wipe cleaning system you might spend a Sunday afternoon cleaning vinyl in the family room. Doing so with the RD-VI would be more akin to operating a hairdryer while the missus is trying to watch telly. Neither can you listen uninterrupted to cleaned LPs while cleaning others, given the regular bursts of suction motor noise.

So the cleaning task can perhaps instead be considered foreplay to your listening enjoyment. It wasn’t so loud that it persuaded us to wear headphones while operating it, though for long cleaning sessions you might consider it, as might anyone else around.

Noisiness aside, it’s great fun to operate the Record Doctor. It’s too low to have on the floor without back-bending, and too high to have on a table without the need to reach above it; it was ideal on a calf-high stool, operated from a knee-high stool.

It took only a couple of records to master the amount of fluid required to fully coat the disc – the fluid bottle has a pull-down nozzle which helps eject only a drip or two at a time. Spreading becomes a combination of turning the record and moving the supplied brush (bottom left image).

Indeed the spreading brush would seem to be the main thing to get saturated and potentially dirty in the Record Doctor system, running damply around the unclean records as it does, so picking up their superficial accumulation of dirt while the liquid and suction does the deeper clean.

We introduced two additional stages to the process, giving each disc an initial dry wipe with a non-shedding cloth to clear any excessive dust before placing it on the Record Doctor, and also giving the spreading brush a cleansing swipe each time prior to application, to ensure we weren’t transferring any dirt collected from the previous disc.

After flipping the disc and replacing the hand knob, you get to turn on that noisy motor and manually turn the record around quite slowly. You can’t, of course, see how well it’s sucking and whether it’s yet dry underneath; the instructions suggest two or three rotations, something like 15 to 20 seconds.

One advantage of this system is that records are immediately dry and ready to return to their sleeves or, indeed, to play, subject to interruption by the next bout of suction noise.

With dunk-and-wipe cleaning systems you’re never entirely sure things are fully dry, especially with cloths getting increasingly damp as you progress through a batch. With some systems you actually have to leave records out to dry, like plates in a drying rack. Here every disc gets the same treatment, and they all emerge dry and ready for use or storage.

Depending on the level of fluid application, the supplied 125ml bottle of RxLP cleaning fluid is expected to clean 25 to 50 LPs, but it’s reassuring to see that you’re not heavily gouged for ongoing fluid purchases, since you can get a large bottle of concentrate for $30 / AU$45 which will dilute to make another 3.8 litres of fluid, enough for around 1000 more LPs.

Before and after

We saved some reference discs until we’d mastered the process and become fully accustomed to the RD-IV’s ways. And by ‘reference’, we do not mean the finest pressings in our collection but rather a range selected as suitable candidates for ‘before and after’ comparisons.

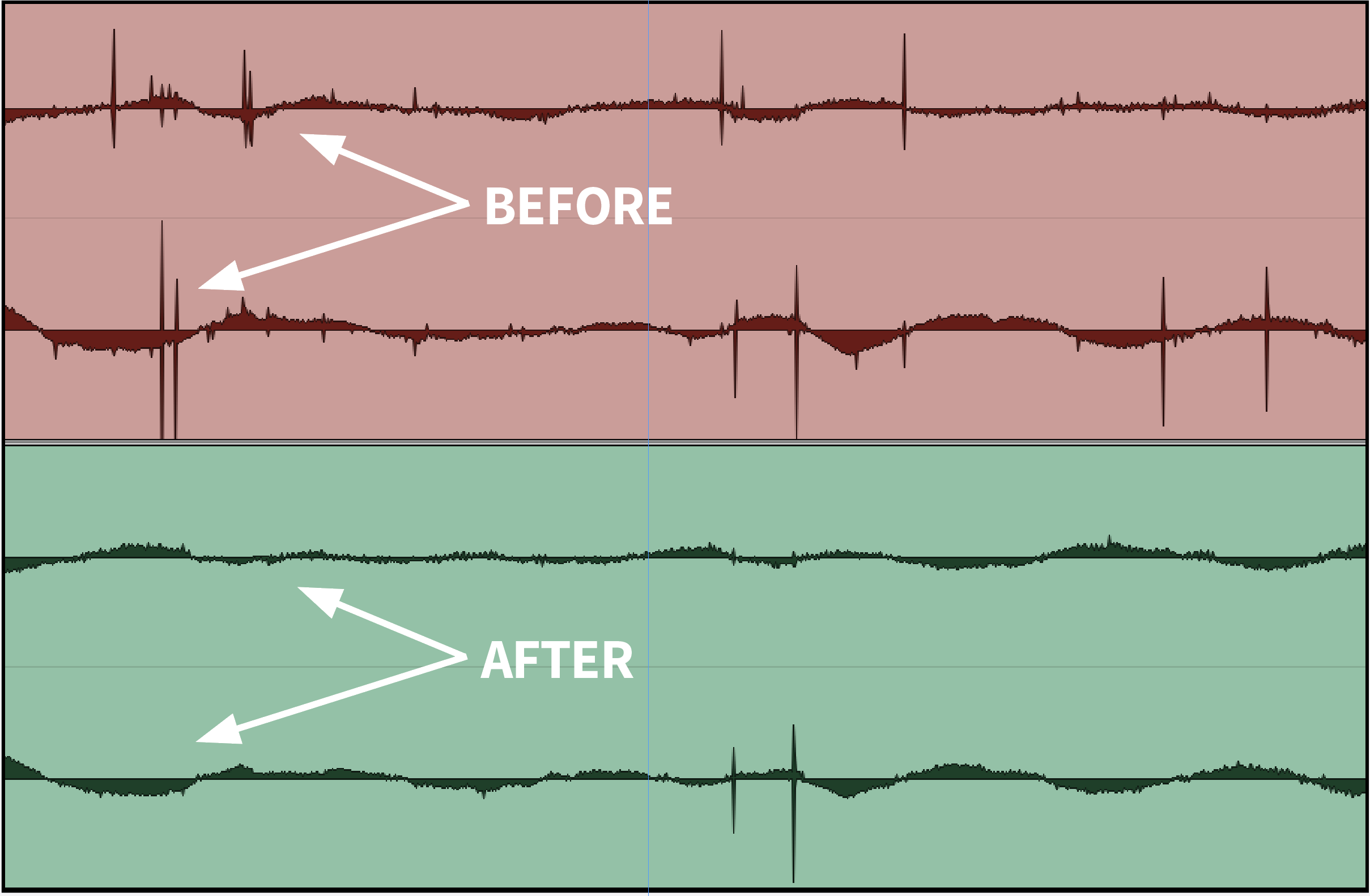

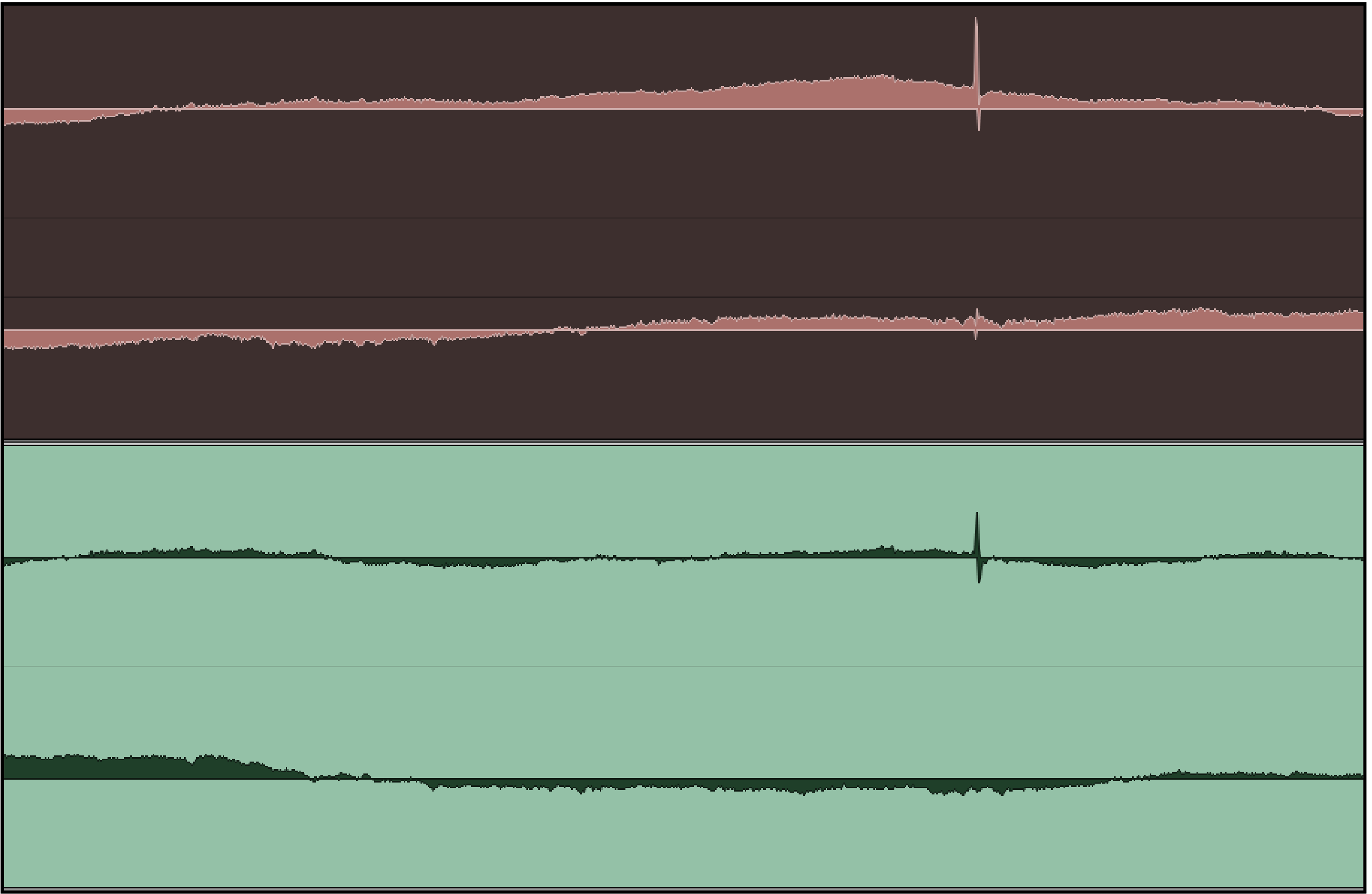

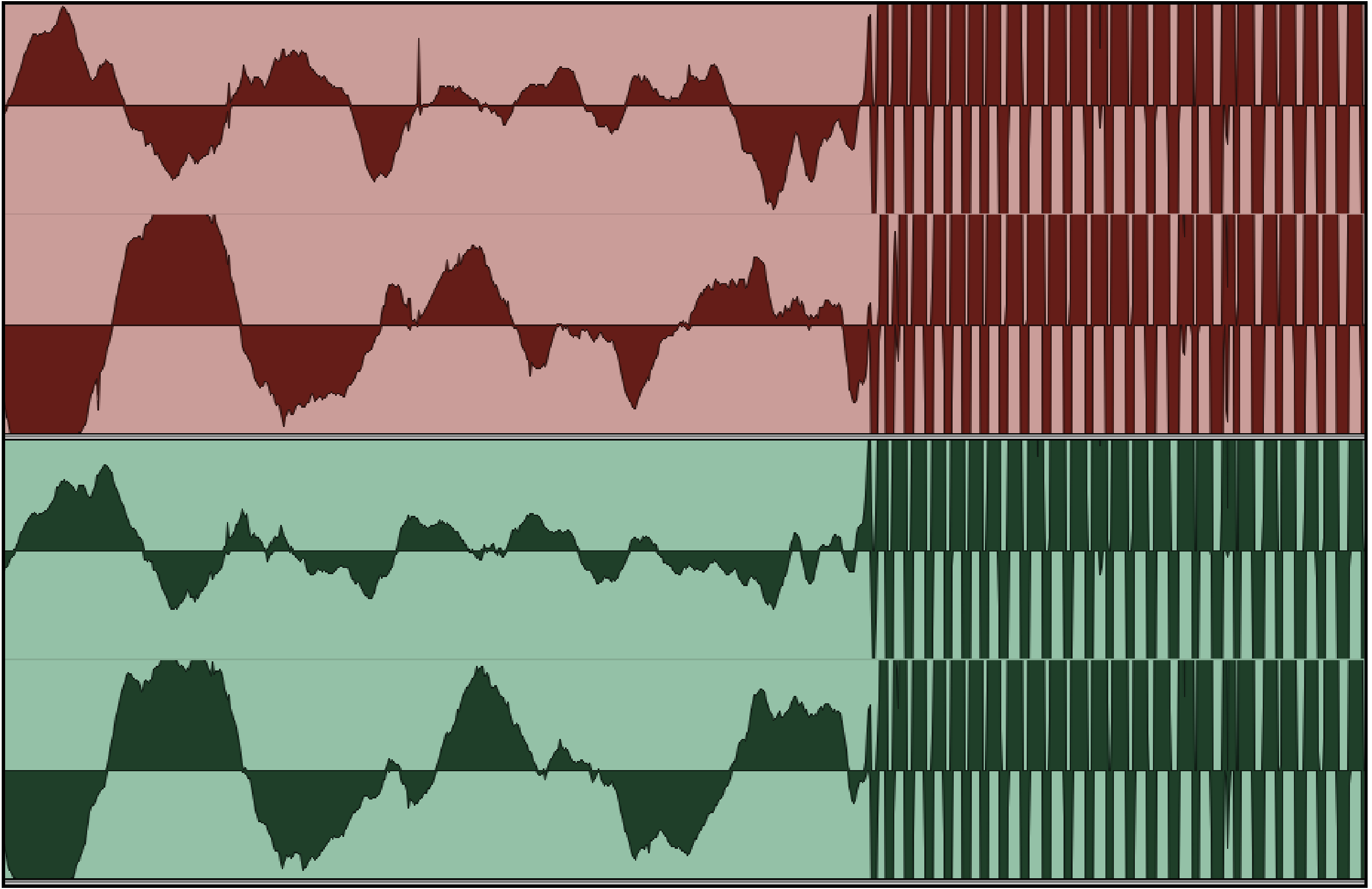

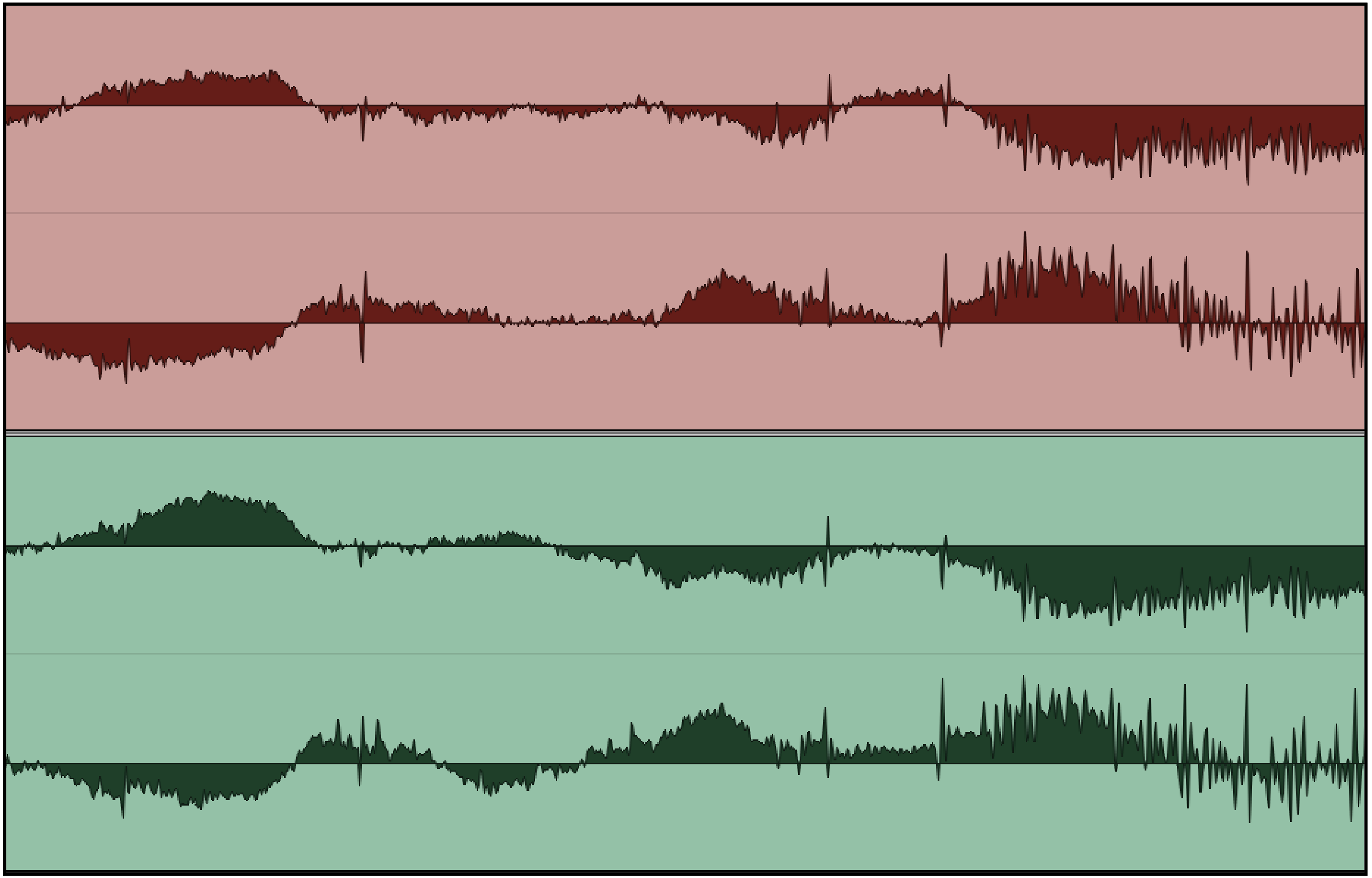

These comparisons were made not only by listening, to see if pops, surface noise and any other audible distortions were reduced, but also by digitising the playback before and after cleaning so we could examine the sound visually, albeit at second (and digitised) hand – in the waveforms reproduced opposite the originals are shown in red, the cleaned versions in green.

We chose two LP acquisitions from the last local pre-Covid record fair: one an LP of Simon & Garfunkel’s The Concert in Central Park which was in poor condition with significant splotches visible when angled to the light, the other a copy of Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours, apparently in reasonable condition.

We also pulled out one of our most played pieces of vinyl, Keith Jarrett’s Changes, on which the first side’s Flying pt1 has good minimal areas in which changes in surface noise might be more easily assessed than over, say, thrash metal.

Our fourth test disc was a near-pristine white label pressing of Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue from Absolute Analogue (which is not one of the highest regarded pressings of this album, sadly).

As expected, there was little difference to be discerned with this last disc in terms of surface noise, this having been kept pristine and already regularly cleaned before play. The waveforms, however, showed that even here persistent clicks could be reduced, with some indication that surface noise was also reduced (the sample shown in the top waveform pair opposite is part of the gap on side one between Freddie Freeloader and Blue In Green).

There were improvements on the Jarrett LP, too, though not sufficient to wash the sound entirely clean. Audibly it was the Fleetwood Mac disc which had the greatest removal of vinyl noise, rescuing this $2 acquisition to earn a place in the record racks instead of ending up a probable reject ready for the eager hands of the next local street clean-up.

The marks on the Simon & Garfunkel disc were too stubborn to be entirely removed even after a second more intense clean. The effect on sound was nevertheless substantial – unlistenably dirty before, the disc was still noisy afterwards but to an extent where we could easily enough listen through the noise and now enjoy the album. The comparison waveforms are from the opening fade up of the crowd, and show a significant removal of the transient cracks where dirt has been displaced.

Sizing down

When we mentioned to Decibel Hi-Fi (the distributor) that we were looking forward to cleaning some of our singles collection, they said they would include the required adaptor for these, admitting “it’s just a bit of hose”. And it is indeed just a bit of hose, split down the side to open it up.

After a bit of thought, and a seven-inch disc in place for guidance, this seemed designed to cover the bit of the vacuum outlet slot which remains uncovered by the smaller disc, thereby maintaining maximum suction pressure on the underside of the 45. It was precision cut for this purpose!

And worked well. We cleaned up some David Bowie singles, including a promo copy of his debut for Deram Records Rubber Band in 1966 (the label marked with a pencil ‘×’ indicating that a BBC producer had rejected it for airplay), and also an appropriate choice for an audio magazine, Bowie’s Sound And Vision single from RCA in 1977.

Both gained (or rather lost) audibly through reduction of clicks thanks to the Record Doctor (see waveforms), especially in the lead-in of the surprisingly loud Deram single.

Final verdict

Records must be cleaned! The latest Record Doctor VI proved an effective and enjoyable way of doing so, more than commensurate with its price compared with cheaper wash-and-wipe systems.

It can’t resurrect deeply abused vinyl, but it can significantly improve many discs which might otherwise be unlistenably noisy, and will most certainly maintain the more treasured discs of a collection in the condition they deserve.

Sound+Image is Australia's no.1 mag for audio & AV – sister magazine to Australian Hi-Fi and to the UK's What Hi-Fi?, and bestower of the annual Sound+Image Awards, which since 1989 have recognised the year's best hi-fi and home cinema products and installations. While Sound+Image lives here online as part of our group, our true nature is best revealed in the print magazines and digital issues, which curate unique collections of content each issue under the Editorship of Jez Ford, in a celebration of the joys that real hi-fi and high-quality AV can bring. Enjoy essential reviews of the most exciting new gear, features on Australia's best home cinemas, advice on how to find your sound, and our full Buying Guide based on all our current and past award-winners, all wrapped up with the latest news and editorial ponderings. Click here for more information about Sound+Image, including links to buy individual digital editions and details on how best to subscribe.