Sound+Image Verdict

The Airbearing turntable is the sole product of Slovenian maker Holbo, and as its name suggests, it takes the novel approach of separating its mechanically moving components with a cushion of air. This results in wonderfully detailed, dynamic and noise-free audio, albeit with a few fussy peculiarities that come with the unique technology involved.

Pros

- +

Lack of background noise

- +

Dynamics & detail

- +

Brilliant soundstaging

Cons

- -

Requires air-pump connection

- -

Airbearings are level-critical

Why you can trust What Hi-Fi?

This review originally appeared in Sound+Image magazine, one of What Hi-Fi?’s Australian sister publications. Click here for more information on Sound+Image, including digital editions and details on how you can subscribe.

From Slovenia comes the latest edition of Holbo’s sole product, this turntable that does a number of things notably differently.

It has only three legs. It keeps its branding to itself, presenting a plinth unadorned other than by buttonry. Its tonearm is very obviously not for pivoting, but adopts the linear tracking method which should, if successful, more closely track the information put into LP grooves by the lathes which cut master discs using the same linear tracking motion.

But perhaps most unconventionally of all, it arrives with an offboard box which is not an isolated power supply, nor an offboard phono stage, but an air pump. It's proudly branded “Holbo Air Pump”.

Which of course means we can chuckle as we insert the following amusing subheading...

Pump up the volume

What precisely is Holbo pumping up, aside from the volume? Bostjan Holc, the founder of Slovenian “artisan company” Holbo, set out to make a turntable in which the moving mechanical parts do not touch each other at all. By eliminating the last vestiges of friction and physical transmission, says his company, micro vibrations and mechanical friction might be eliminated, and music could be revealed in all its magnificence, dynamics and musicality.

How to achieve this? With what Holbo calls an airbearing system, which places the platter on a bearing of air. That’s not floating around in mid air like a magic trick, as on the recent Mag-lev turntable, but rather using an air-bearing for the spindle instead of mechnical contact, whether oiled or not. Indeed Holbo here doubles down on the theme ingredient, as the tonearm also moves on a bed of air. But from where does this cushioning supply of air come from?

Type: belt drive, manual, w. air-pump/power supply

Speeds: 33⅓, 45pm, electronic switching

Plinth material: MDF

Platter: 5kg coated aluminium

Outputs: phono-level RCA with ground

Dimensions (whd): 430 x 400 x 150mm

Weight: 12.0kg

Tonearm: Linearl-tracking airbearing

Total tonearm mass: 31.6g

Effective tonearm mass: 7.5g

The answer is the air pump, and indeed on this latest Holbo Mk II Airbearing Turntable System it’s a combination air pump and external power supply (in the Mk I version, these were separate units). In addition to twist-locking the power cable between the external box and the main turntable, you also attach a plastic tube between the two, neatly fitted with a similar twist lock to hold it in place at both ends.

This then feeds air to both the platter bearing and the tone arm bearing. When you hit the left of the two buttons on the front of the plinth, the power and pump start up, air is sucked into the pump through a small cork filter, and then out again via the tube to service both air bearings in the turntable.

Linear tracking

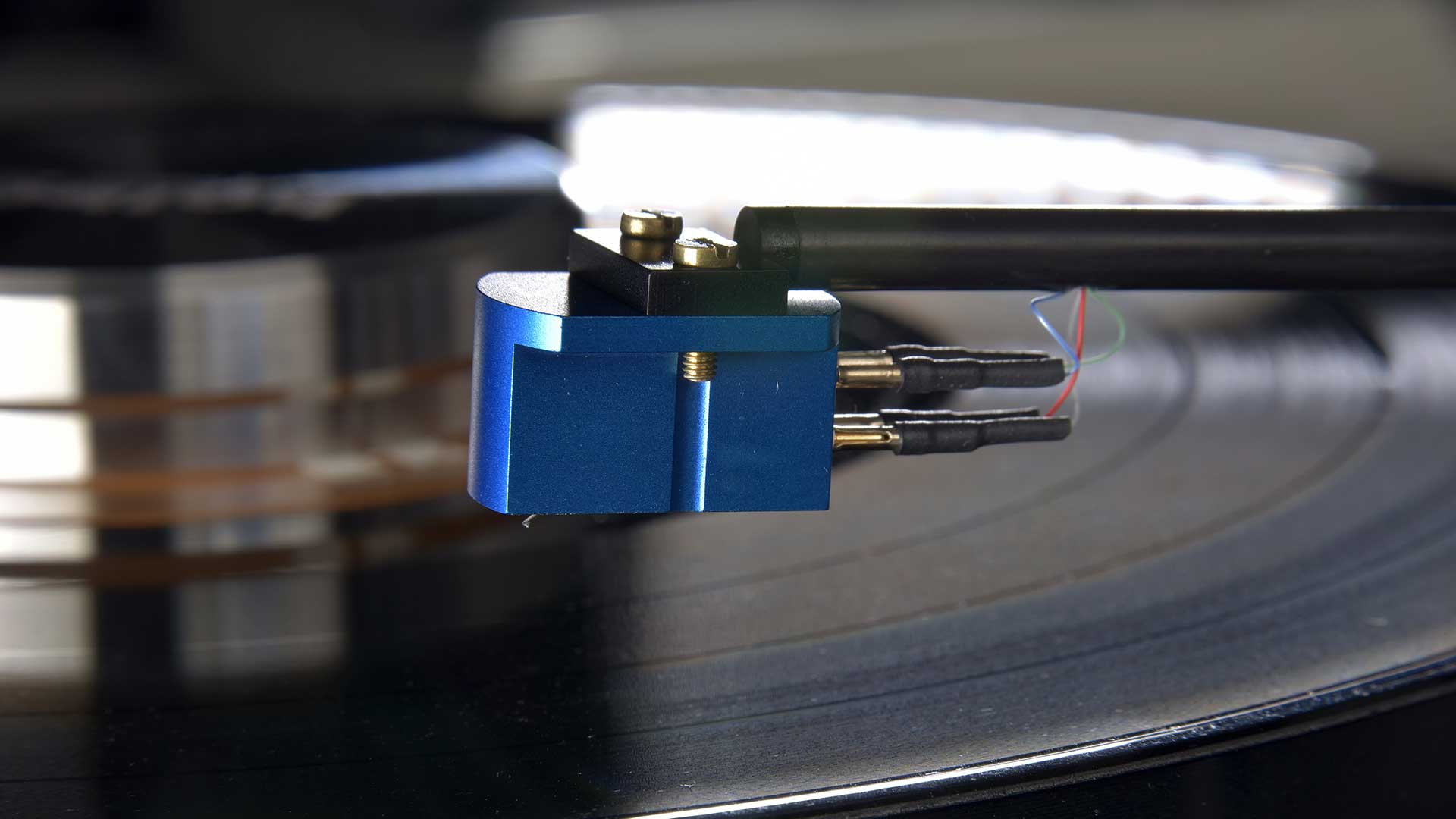

You’ll note that the Holbo’s tonearm, unlike anything else in this group of turntables, uses linear tracking, not the more common pivot. Instead of rotating around a fine pivoted bearing, the arm and its bearing slide along a fixed rail.

Why do this? The question really should be why wouldn’t you do this. This is how records are cut: the lathe and cutting stylus which put the information into the groove in the first place are on a linear tracking system, with the arm sliding along a rail, kept parallel to the groove tangents. A linear tracking playback system clearly has a huge advantage in maintaining the same geometry.

By contrast, the angle of a pivoted tonearm is non-parallel to the groove except at one or two places on the disc. Elsewhere the tracking error increases to a maximum at the start and end of the disc.

The main ways to combat this are a century old – offset and overhang, as defined by American Percy Wilson over two articles in 1924 issues of The Gramophone, although Mr Wilson’s generally-recognised primacy in this regard has since been challenged by the discovery of a French patent filed in 1907 by Hungarian merchant Bela Harsanyi.

But each described the mathematics of offset and overhang which can minimise tracking errors to a maximum of 2% over the complete arc required to play a disc – noting only that the advent of the LP changed the size of the disc and that further correction was later introduced to handle skating forces.

Thus began the joys of cartridge alignment. Still, with 2% tracking error pivoted tonearms still don’t match the theoretical accuracy of a 100% tangential linear tracking system. So why aren’t linear trackers more common?

Mainly because it’s extremely hard to achieve the freedom of movement required for a cartridge reading the groove from an arm which must overcome the friction of sliding along a bar. Some are pushed along by servo motors, which react to resistant groove forces by nudging the arm along its rail, although this affects horizontal movement before and after each nudge, first restricting then pushing, so that the tracking is affected that way.

Body: aluminium alloy, 25mm long

Cantilever: solid boron rod: 0.28mm diameter

Stylus: 0.12 x 0.12 Nude line-contact diamond, mirror polished

Stylus tip radius: 4 x 70μm

VTA: 20 degrees

Coilbody: pure iron

Weight: 7 grams

Output voltage: 0.40mV at 5cm/s

Internal impedance: 40 ohms

Frequency response: 20–25.000Hz ± 1dB

Channel separation: 35dB at 1kHz

Meanwhile the servo can introduce its own vibrations. Another problem can be inertia created by the cables coming from the cartridge, dragged along as it moves, which can put additional and unpredictable forces on the arm and cartridge.

The upshot is that cheap linear trackers underperform, suffering from their own issues of vibration and wobbling, while a well-designed linear tracker is generally very expensive. Even then some vinyl fans love them; others won’t touch them.

But the servo problems, at least, can be well addressed by ditching the servo and instead providing freedom of movement by using an air bearing between the arm and the rail. Holbo’s is not the first in this regard – Kuzma, Rockport, Airtangent and others have tried the trick in the past.

This method brings new issues to overcome, not least of them the need for that air pump, introducing its own potential vibration and noise, while adding an additional air tube to attach to the moving arm, adding to the potential inertia of the hanging cables.

From our time with the Holbo, this turntable seems to overcome these objections nicely – with one very important proviso.

Setting up

We confess that we ducked one important part of setting up this turntable – installing and aligning the cartridge. The MkII turntable and its combo pump together sell for £6,000 / AU$12,000, cartridge not included. Distributor Audio Marketing and the Len Wallis Audio team provided us with a Holbo equipped with a Kiseki Blue N.C. moving-coil cartridge pre-installed and aligned.

This is a clever choice, as Holbo’s Mr Holc has recommended a number of Koetsu cartridges, including the Black, and of course Kiseki, which means ‘miracle’ in Japanese, was set up in the 1980s by Dutchman Herman van den Dungen, who commissioned Japanese cartridge makers to create something that would compete with the Koetsu Black, and the original Kiseki Blue was the result.

The company subsequently did well, partnering with Dan D’Agostino’s Krell, but declined and fell during the CD era before reappearing in 2011, using existing parts to make 105 new Kiseki Blues before introducing the Kiseki Blue N.S. (New Style) for ongoing production.

The Kiseki Blue cartridge retails for AU$3095, pushing the combination here above AU$15,000. A feather-light pair of Inakustik air-dielectric interconnects, priced at AU$1,495 the pair, were also supplied to connect to a Musical Fidelity phono stage.

The rest of the procedure was surprisingly plug and play. The air tube connects as easily as the power supply, and comes with a good 100-inch length of tubing, so you can physically separate the air pump from the turntable. Indeed, in the early days of air-bearing turntable pumps, some users would run the tubes through a wall so the pump could be in another room! But we never once heard a peep from the Holbo

airpump, so you needn’t worry about air-borne sonic pollution. As for any physical vibration, using an adjacent equipment rack seemed to provide adequate separation to ensure no transmission of vibration.

The plinth is clean of markings, black and solid, the total construction weighing 12kg. The platter contributes 5kg of black anodised aluminium, and is slightly smaller than albums, so they’re easy to remove. You also get a metal disc puck to weigh down (but not clamp: there is no threading) records that are placed on the platter; Holbo-branded, so presumably not overloading the air-bearing.

Speed change is the second button on the front left of the platter, switching between 33⅓ and 45 rpm, with the adjacent LED changing from red (33⅓) to green (45).

There’s no dust cover, which is always a disappointment, whether for keeping things clean when not in use or for the benefit of blocking audio feedback when playing loud.

Another thing requiring care is the cueing lever. The Kiseki cartridge has no finger-lift, so the cueing lever is compulsory, and it is relatively undamped, so needs careful lowering, and it also moves non-intuitively backwards rather than forwards to lower the needle.

You become accustomed to this pretty quickly, though its position far back behind the tonearm rail remains a little inconvenient.

Performance

The biggest thought adjustment required from the outset is that you can neither rotate the platter nor move the arm on its rail until the pump is turned on. (In fact you can slide the arm against the friction then encountered, but you can feel that the Holbo doesn’t like it, so we did this as little as possible!)

We had also been warned that levelling of the platter was critical, and also that the spikes of the Holbo’s feet are unusually sharp, so that we might want to use the supplied metal discs under those feet if we valued our turntable shelf! We’re not precious, so we didn’t use them at first – but then, after rotating the turntable to connect cables, we found one of the feet had indeed gouged out a nice trough in our shelf, so we got those discs out after all…

And we levelled the deck carefully with a bubble guide. There are only three feet to the Holbo, two of which are adjustable. So it’ll never wobble, but it really does need to be 100% level, as we discovered.

With the cartridge having been prealigned, we were up and playing pretty fast – a little too fast, indeed, as our strobe and the RPM app indicated the Holbo’s speed to be a full 3%+ above the desired speed, rendering everything a semitone high. A small flathead watchmaker’s screwdriver allowed us to tweak this to perfection via a small screw at the rear (one for 33⅓, then another for 45).

With the speed accurately set, several things about the sound were immediately evident. First was the level of detail, the clarity and stability of the soundstaging delivered from the Kiseki/Holbo combination. But even more than this was the feeling of background silence above which this was raised.

Playing an original Australian LP of the 1970 Beatles’ ‘Hey Jude’ compilation of non-album singles and B-sides. It’s a great pressing, and on the title track opening side two, Paul McCartney’s bass can emerge remarkably full and solid. We’ve heard it delivered to greater depth than the Holbo did, but with that imaging and realism created by the extraordinary lack of distortion, never have we had this album delivered so truthfully; the decades dropped away and we were in the room.

Just as Peter Jackson has cleaned up the ‘Get Back’ video to look so immaculately immediate and real, the Holbo did the same with the music from this album’s groove with this turntable’s effortless separation and lack of distortion allowing fantastic insight into the details of the recording.

We say lack of distortion, but on the third track, Don’t Let Me Down (a song one forgets never made it onto the album ‘Let It Be’), we heard something we’d never heard before.

A splash cymbal positioned front left in the mix sounded like it was overmodding its mike; there was audible distortion on it. How had we never noticed this before? Then suddenly the unthinkable happened – the stylus jumped backwards, repeating the groove three times before moving on. This is not an LP with any known scratches, so WTF? The rest of the side played fine. With the next album, we were a couple of tracks in when again left-channel distortion became notable on high frequencies and, dammit, it jumped again.

Jumping a Kiseki Blue cartridge is not something we wanted to do, so we stopped listening pronto. We kept the pump running and manually checked the movement of the arm along its rail. There was definite resistance right in the middle of the movement, surely the reason for the arm sticking in that track – and surely also the cause of the distortion we’d heard as the Kiseki was pulled against the outside of the groove. Were the hanging cables and tube pulling the arm? It didn’t seem so. What could it be?

Our levelling was to blame. It was perfect left to right, but a teeny bit off front-to-back. We adjusted the feet some more, until it seemed perfect. Back to the Beatles – no distortion, no jumps: perfect playback.

So take this as a warning that the airbearing for the arm, at least, is intensely level-critical.

After that, the fine performances proceeded glitch-free. The Holbo threw itself behind the 40th anniversary box-set pressing of Queen’s ‘News of the World’ (a pure analogue pressing from original tapes to lathe), monster-booting the stomps of We Will Rock You before the crystalline cut to the ensemble mix of We Are The Champions.

With this level of clarity we could hear those stacking centre harmonies self-flanging as they interact, even more so on the extended ‘sheeeeeeer’s of the following Sheer Heart Attack, those rising screams defined perfectly by the Kiseki even over the maelstrom of guitar, bass and drums (all played by Roger Taylor), while May’s subsequent high-pitched guitar solo shrieks arrived with extraordinarily ear-piercing intrusion – a reminder how high the response of vinyl can rise from a revealing system.

By comparison the lead vocal was miked within an acoustic that sounded sung from a sunken lounge suite. All in all this was a revelation of the mixing behind this album, as well as the ability of the vinyl system to keep it all fully resolved.

The piano tones on the opening of Brian May’s song All Dead All Dead were entirely without wobble, this majestic arrangement expanding to fully fill the soundstage, and delightfully fresh still after now 55 years, even with its pathos punctured by the recent admission that it’s about Brian May’s cat.

It’s when there are gaps – such as the near dead stops between verses in Spread Your Wings – that you realise there’s no underlying presence behind the music whatsoever, a real nothing, so that the dynamics can expand fully from such silence. It was the rising from such depths in the gaps that we found the most exhilarating thing of all with the Holbo.

Also the punch that this allows. Witness the last track on this Queen vinyl side, Fight From The Inside, the second Roger Taylor song, with his kick drum truly thwacking you in the gut from the outset, yet the whole mix retaining a wide open stage for the choruses and especially the bridges where the sound opens out more cleanly from the chunky set of chugging guitars through the verses.

This is all the greater achievement being the innermost track of the side, where pivoting arms have their hardest task. With linear tracking this song was opened up as wide as any. What a 20 minutes of vinyl that was!

While shelf searching a little to the north of Queen, we happened upon a copy of the ‘Kiss Me, Kate’ original Broadway sound-track album (with the “original, sometimes pungent, lyrics”, according to Miles Kreuger’s sleeve notes). This we’d picked up who knows where for something close to nothing, since put through at least one deep cleaning process; the grooves looked positively pristine.

How huge the overture burst forth! How spacious and natural the acoustic on the chorus singers. What a weird voice Lorenzo Fuller has! – but how clear every swoop of his tone as you lean in to sit closer into the soundstage. It’s enough to convert you to musicals.

As the songs continue, it becomes apparent that the sound mixers are mimicking the stage movements, with soloists and couples wandering or, in the case of Wunderbar, clearly waltzing around the soundstage. The Kiseki tracked their movements perfectly, the individual tones of each vocal panning smoothly amid the full musical mix. So In Love, what a song! (Though we suspect that today Cole Porter would be ‘cancelled’ for giving Ann Miller the outrageous arrangement of the song Tom, Harry or Dick...) Was there a slight tendency to distortion on central high soaring vocals?

Given the source of the vinyl, it was hard to ascribe blame directly to the Kiseki/Holbo combination, rather than the pressing or the vinyl’s uncertain provenance. We did try tweaking the resistance loading on the Musical Fidelity phono stage, but the manufacturer’s suggested 400k surely suited the Kiseki Blue best, so we left well alone.

Seeking stuff to transcribe while in the presence of such clarity, we loaded a live LP by UK neoprogs IQ, and set it playing direct to the speakers, while also recording to Mac from the ‘tape’ outputs of the amplifier through which we were listening. By now that initial impression of bass being underplayed seemed entirely unjustified, with both electric and electronic bass reaching down to excite the subwoofer we had underpinning our already substantial monitors.

We were also rewarded a demonstration of pace and timing for the breathless prog pace of It All Stops Here, a live IQ classic we suspect we haven’t have heard since bouncing in moshpits in the mid-80s, yet to which we were able to sing along most of the words. The longevity of musical memory is extraordinary sometimes.

By recording the output of the Musical Fidelity phono stage we could also compare the performance here with many other turntables recorded the same way, with the same tracks, over the last five years. It was a reminder that vinyl performance increases fastest in the low thousands of dollars, yet the Holbo/Kiseki combo delivered something beyond, with that impeccable background silence a unique defining characteristic.

Final verdict

Given a perfect set-up (since the Holbo is notably picky about being absolutely level), this combination wowed us with its clarity of reproduction and the openness of its soundstaging, with everything lifted above the sonic void created by cushions of air.

(All images: Studio Kai)

Jez is the Editor of Sound+Image magazine, having inhabited that role since 2006, more or less a lustrum after departing his UK homeland to adopt an additional nationality under the more favourable climes and skies of Australia. Prior to his desertion he was Editor of the UK's Stuff magazine, and before that Editor of What Hi-Fi? magazine, and before that of the erstwhile Audiophile magazine and of Electronics Today International. He makes music as well as enjoying it, is alarmingly wedded to the notion that Led Zeppelin remains the highest point of rock'n'roll yet attained, though remains willing to assess modern pretenders. He lives in a modest shack on Sydney's Northern Beaches with his Canadian wife Deanna, a rescue greyhound called Jewels, and an assortment of changing wildlife under care. If you're seeking his articles by clicking this profile, you'll see far more of them by switching to the Australian version of WHF.