What Hi-Fi? Verdict

The sensitivity and sonic balance of Dali's new Oberon 9 loudspeakers will ensure realistic reproduction of music, no matter what the genre

Pros

- +

Massive bass

- +

Super efficiency

- +

Great midrange clarity

Cons

- -

Grilles hinder audio

- -

Too easy to topple

- -

Basic feet and spikes

Why you can trust What Hi-Fi?

This review and test originally appeared in Australian Hi-Fi magazine, one of What Hi-Fi?’s sister titles from Down Under. Click here for more information about Australian Hi-Fi, including links to buy individual digital editions and details on how to best subscribe.

The Dali Oberon 9 is the newest and largest loudspeaker in the Oberon range.

If the model name rings a bell, you’ve obviously seen William Shakespeare's play ‘A Midsummer Night's Dream’ in which the Oberon character is the king of all fairies, but Shakespeare borrowed the name from ‘way back in the 13th century, at a time when Oberon was merely an elf.

As for the model number, it seems to suggest that there are nine models in the Oberon Series, but in fact there are only seven. The number is actually the diameter, in inches, of the two bass drivers fitted to the Oberon 9’s front panel.

If you’ve guessed that the model beneath it, the Oberon 7 has seven-inch drivers, and that the Oberon 5 has five-inch drivers, go to the top of the class. But if you then infer that the Oberon 3 and Oberon 1 have three inch and one-inch bass drivers respectively, you wouldn’t even be close. (They have seven-inch and five-and-a-quarter inch drivers respectively.)

Oberon may have started out as an elf, but there’s nothing at all elfish about the Oberon 9, because they stand a dauntingly-high 1.17-metres high. They also have an impressive armada of drivers on display – two bass drivers, a midrange driver and a tweeter. We need to look at the design in some detail, because there’s a lot that’s new and different about this new model from Dali.

Equipment

If you have already twigged that a 9-inch (230mm) diameter for a bass driver is fairly unusual, it comes about because Dali is one of the few manufacturers that builds its own bass drivers. Most manufacturers purchase drivers from companies that build only drivers, and those companies tend to build drivers in pretty standard and very specific diameters. Usually, because everything originally started in imperial measurements, those ‘standard’ driver diameters are (for bass drivers) 6-inches, 8-inches, 10-inches, 12-inches and 15-inches – increments that don’t look nearly as uniform if you look at the metric equivalents, which are 153mm, 203mm, 254mm, 305mm and 381mm.

So if any other speakers you might be considering buying have bass drivers that fit into one of the standard driver diameter increments, there’s a good chance they were not made by whosever name is emblazoned on the grille cloth of those speakers. And if that manufacturer is also claiming something about the drivers it’s using is ‘unique’ in any way, it’s not – because that same technology would be available to all other manufacturers using that same driver.

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

So why did Dali decide to build a 9-inch driver? The obvious reason is simply because it could!

The less obvious reason is that the larger the cone diameter, the greater the area of the cone, and the greater the area of the cone, the more air it can move. And, to bring this train to its obvious last stop, the more air a driver can move, the better the bass! So if a ‘perfect’ 8-inch driver could move 327 square centimetres of air, the ‘perfect’ 9-inch driver would move 416 square centimetres of air. That’s about a 27 per cent increase in surface area. (Pedants please note that these figures are based on the Thiele/Small diameter, not the actual chassis diameter).

But you don’t really need to look at the diameter of the driver to tell you that Dali is building its own drivers. Just take a look at the cones. The only other place you’ll see a cone like that is on another speaker made by DALI. It’s that unusual.

So what is the cone made of? Actually it’s a wood pulp product, not unlike that used by other driver manufacturers using so-called ‘natural’ plant materials for their cones. But instead of completely pulverising the wood it uses, like other cone makers, Dali has elected to include wood fibre reinforcement by actually embedding larger wood fibres into the pulp. It also doesn’t bleach the cones, so not only is the cone’s surface a bit uneven, due to the larges fibres, but it’s also a rather ‘woody’ colour. It’s also more environmentally friendly to use unbleached cones. Dali says that the uneven surface minimises cone resonances.

Yet another unusual feature of all three of the cone drivers Dali is using on the Oberon 9 is that the central ‘dustcap’ is made from exactly the same material as the cone, and is dished to follow the cone’s profile. You need only glance at a few other speakers to realise that many manufacturers make the dustcap from a different material to the cone, and fix it to the central part of the cone like a mini-dome.

The larger cone size is complemented by a larger (and four-layer) voice coil, which means higher efficiency, higher power handling, and less distortion because the cone doesn’t have to move backwards and forwards as much as a smaller cone in order to create the same sound pressure levels, so the motor system (magnet and voice-coil) operate in the most linear region of the magnetic field.

The large drive magnet is made from ferrite (as are most driver magnets at the Oberon 9’s price point) but the pole-piece is made from a cylinder of iron at the top of which is a disc made from a proprietary material Dali calls a ‘Soft Magnetic Compound’ or ‘SMC’.

The SMC disc’s purpose is essentially the same as the ‘flux shorting rings’ or ‘Faraday rings’ used by some other manufacturers in their drivers. The concept behind all these devices is that they counteract the eddy currents and flux modulation induced by the voice coil as it moves through the magnetic field. They also help linearise the inductance as input current varies. The end result is reduced distortion, both harmonic and intermodulation (THD and IMD).

Interestingly, although Dali puts the diameter of the bass drivers at 9-inches, my tape measure put the overall chassis diameter at a shade over this, at 9¼ inches (235mm). I was pleased about this, because many manufacturers ‘over-quote’ the dimensions of their drivers to make them seem larger than they really are. But of course the important dimension is the Thiele/Small diameter, which is what tells us how much air the driver will move, and for the Oberon 9’s driver, that was 180mm, which puts the effective cone area (Sd) at 254cm².

However, because there are two drivers producing bass in this design, the overall area available to move the air in your room is twice this, or 508cm². This means that if Dali had decided to build a single driver that had the same cone area and install this in the Oberon 9, it would have had to have had an overall diameter of around 310mm, or a bit over 12 inches, which would have been too wide to fit into the cabinet, which is only 260mm wide.

Midrange driver

The first important thing to note about the Dali Oberon 9’s midrange driver is that it’s there at all. By which I mean to emphasise that this speaker is a true three-way design, where the low frequencies are handled exclusively by the two bass drivers, the high frequencies are handled exclusively by the tweeter (about which more in a moment) so that the frequencies in-between – the midrange frequencies – are handled exclusively by the midrange driver.

Why is this so important? It’s important because of a peculiar type of distortion called phase modulation distortion, or PMD. Phase modulation occurs when a single speaker cone is called upon to reproduce low and high frequencies simultaneously, which is what happens in all two-way (and 2½-way) loudspeakers.

If a driver is required to produce a single low-frequency sound (at, let us say, 55Hz), its cone will move backwards and forwards fifty-five times per second and your ear would hear the resulting movement of air caused by this movement as the musical note ‘A1’. This pitch is an octave above the lowest A on a piano keyboard and also the one to which the second string of a double-bass is tuned. So far so good.

But if that same driver is also asked to produce another musical note, let us say middle-C, which has a frequency of 261.63Hz, it would have to move backwards and forwards 261.63 times per second at the same time that it’s also moving backwards and forwards 55 times per second. This means the frequency of what should be ‘middle-C’ will actually not always be precisely 261.63Hz but will be shifted up to 55Hz higher or lower (depending on the direction the cone is moving) as a result of having to produce the 55Hz signal at the same time.

It’s because of phase modulation distortion (PMD) that it’s preferable that a low frequency driver (or drivers) be used to produce low frequencies and for a completely separate loudspeaker to be used to produce midrange frequencies. (For more information about PMD read the article ‘Doppler distortion in loudspeakers – Real or Imaginary?’ by Rod Elliott, at https://sound-au.com/doppler.htm in which he not only discusses and explains phase modulation distortion in great detail, but also demonstrates how it affects loudspeakers by actually measuring it.)

Another important thing to note about Dali's midrange driver is that its construction is the same as that of the bass drivers, using the same cone and roll surround materials. This means that the sonic ‘signature’ of the driver will be the same as that of the bass drivers. In designs where a midrange driver is of different construction to the bass drivers, it will have a different sonic signature, which is obviously not desirable.

Anyone living in Australia (or New Zealand) should also note that the surrounds of both the bass and midrange drivers are made of rubber. This is very important for longevity in both countries; because of the high levels of ultraviolet radiation, drivers that use foam surrounds tend not to last very long (sometimes, in fact only just long enough for the loudspeaker to be no longer covered by warranty). Rubber is a far more durable material.

Tweeter

The soft-dome fabric tweeter in the Oberon 9 is also a strange size. At 29mm it’s midway between the two more usual tweeter diameters of 25mm and 32mm. This is because, yep, you guessed it, Dali makes its own tweeters as well, and it says the one in the Oberon 9 was specifically developed for the Oberon Series, with the larger dome size enabling it to perform better at lower frequencies than a 25mm diameter dome, while performing better at high frequencies than a 32mm diameter dome.

So far as the tweeter’s drive magnet is concerned, Dali is using a tried-and-tested ferrite magnet rather than one of the new neodymium super-magnets. This means that there’s more than enough metal and surface area to dissipate unwanted heat that would otherwise cause dynamic compression.

Dali says the ultra-light fabric it uses to fashion the dome weighs 0.060mg/mm² which the company claims makes the dome less than half the weight of most other soft dome tweeters and therefore reduces its inertia.

The tweeter sits at the bottom of a very small horn that improves the tweeter’s efficiency and controls its dispersion. I initially thought those dots on the large circular plate that surrounds the dome and horn were actual dimples in the surface of the material, which many manufacturers use to help smooth the high-frequency response, but when I examined them closely, I found they’re just painted on, so they serve no acoustic purpose at all.

Why is the tweeter positioned below the midrange driver, rather than above it? Dali doesn’t say, but it’s not an uncommon arrangement. It could be in order that the tweeter is 90cm above floor level, which would put it at the ideal height for most seated listeners, or it could be in order to minimise ‘ceiling bounce’ caused by the sound from the tweeter reflecting from a low ceiling. Or it could be for both reasons.

Cabinets

The Oberon 9’s cabinet is made from high-density MDF that’s covered in your choice of vinyl finish – black ash or walnut – though no matter what finish you choose, the front baffle will come in a black satin finish. Internally, the cabinet design is quite unusual because the two bass drivers are each in their own totally separate enclosure, with each one ported to the rear.

This is unusual because most speakers that use two bass drivers have those drivers ‘share’ the same volume of air inside the cabinet. I rather like Dali's method because it means that the output from the rear of one bass driver cannot affect the rear of the other. It also minimises the potential for ‘organ-pipe’ resonances that can affect tall enclosures. There’s a further benefit too, which is that the internal baffles required to separate the drivers increase the cabinet’s rigidity by acting as braces, again reducing the potential for cabinet resonances. The midrange driver is also in its own enclosure, completely isolated from both the bass chambers.

The Oberon 9 has a completely different grille design from other models in Dali’s range (except other models in the Oberon Series). Instead of being flat, it’s curved outwards, into the room. Dali has achieved this by creating an ABS moulding that’s perforated with hundreds of small holes, then covered with black (Dali calls it ‘Shadow Black’) fabric. The company says of this new grille design that: “The new rounded front grille adds a lighter and more contemporary visual look to the speaker series.”

I actually preferred the look of the speakers without their grilles, because I thought the speakers looked a bit ‘monolithic’ with them in place, and I rather admired the black satin of the baffle and the woody look of the speakers, so I didn’t end up using them for my listening sessions.

As you can see from the photographs, the Oberon 9 sits on an aluminium base that, quite unusually, comes pre-attached right out of the packaging (most bases are supplied as separate items). Perhaps because of this, the base isn’t that much wider than the cabinet itself, increasing the cabinet’s 260mm width to 340mm, so it doesn’t do much to improve the stability of this tall (1172mm) and heavy (37.1kg) design.

I found that although the speaker was moderately stable side-to-side, and also stable in the ‘backwards’ direction, it was relatively easy to push forward, due to the cabinet’s dimension in this axis and the fact that all four drivers with their heavy magnets are at the front of the cabinet.

Dali supplies ‘spikes’ and rubber feet that can be attached to the aluminium base, but these are not what I expected. The ‘spikes’ are the smallest and most basic I have ever seen, being simply a 13mm long cylindrical section of threaded black steel, one end of which has been sharpened.

The short thread means that after you’ve screwed them into the base, there’s not enough left protruding to allow much adjustment, and there’s no-where near enough to penetrate though thick carpet and underlay to reach the underlying structure. Luckily the thread is a standard size, so if you need adjustable, carpet-penetrating spikes, you’ll be able to fit aftermarket ones.

As for those rubber ‘feet’, these too were really basic, being an ‘off-the-shelf’ peel-off/stick-on item made by 3M that are just 11mm in diameter and 3mm thick. They will certainly do the job of protecting your floor’s surface, but I would recommend buying and fitting a set of more substantial rubber feet.

What's in a name?

Dali says its name is an acronym for Danish Audiophile Loudspeaker Industries. So it must be true. But it wasn’t always so. Long before current CEO Lars Worre became a major shareholder in the company, the letters stood for Danish American Loudspeaker Industries.

That earlier acronym was coined by the company’s founder and still majority shareholder Peter Lyngdorf, who has also founded and/or owned many other famous hi-fi companies including NAD, TacT Audio, Steinway-Lyngdorf, Snell Acoustics, Gryphon, and Soundbox. He also founded (and still owns) a chain of hi-fi stores called HiFi Klubben, which has outlets in Denmark, Sweden, Germany, Norway and the Netherlands.

Dali was originally founded to manufacture US-designed Cerwin-Vega loudspeakers for sale to Lyngdorf’s HiFi Klubben stores as well as to other retailers in the UK and throughout Europe. Due to customs tariff controls in place at the time, plus the cost of freight, and a poor exchange rate against the US dollar, it was very expensive to import US-made Cerwin-Vega loudspeakers into Denmark and Europe.

Dali was founded to circumvent these costs by importing only the Cerwin-Vega drivers and crossover networks (which did not attract a tariff, and were easier and cheaper to ship than complete speaker systems) which were then installed in cabinets built entirely in Denmark. This was initially a joint operation in partnership with Cerwin-Vega, hence Danish American Loudspeaker Industries. Dali only ceased manufacturing Cerwin-Vega speakers in 1999.

The Oberon 9 is not manufactured in Denmark, but in Dali's own 5,500-square-metre factory in Ningbo, China, a factory it established in 2007 which not only makes completed speakers but also makes many of the parts used in the loudspeakers that the company does build in Denmark. Many Dali parts, including drivers, are also manufactured entirely in Denmark, in the company’s mammoth 22,000-square-metre factory in Nørager, just outside of Aarhus (on the east coast of Denmark’s Jutland peninsula).

Listening sessions

Some loudspeaker manufacturers do not give positioning instructions at all, whilst others are very vague about where they think you should put their speakers in your room. Dali is one of the few that’s very specific about where it thinks its speakers will work best.

Says Dali: “The speakers are designed to meet our wide dispersion principle, so they should NOT be angled towards the listening position, but be positioned parallel with the rear wall, see Figure 2. By parallel positioning, the distortion in the main listening area will be lowered and the room integration will be improved. The wide dispersion principle will ensure that sound is spread evenly within a large area in the listening room.” The company then goes on to say “The speakers should ideally be positioned minimum 20cm (8”) from the rear wall.”

I followed these installation rules to the letter and it proved that the engineers at Dali knew what they were talking about. Not only was the bass response massive as a result of this positioning, but there was a very wide ‘sweet spot’ so that stereo imaging was flawless. And, despite the listening position being essentially off-axis because the speakers were not angled inwards (Dali says “Dali speakers are not designed to be toed-in”), the high-frequency sound was beautifully balanced against the midrange and treble.

The bass response from the Oberon 9s is super-impressive. It’s fast, taut, totally dynamic and essentially distortion-free. It was so well-extended to the bottom-most octaves of music that I’d imagine that few – if any – listeners would consider a subwoofer necessary unless, perhaps, the Oberon 9s were being used as the front channels in a 5.1-channel sound or home theatre system, in which case you’d need a subwoofer in order to fill that “point 1” position.

There are very few reasonably-priced home loudspeaker systems that can do justice to pipe organ recordings, and the Dali Oberon 9 speakers are amongst these few. Even if you’re not a pipe organ aficionado, you should do yourself a favour and use a pair of Oberon 9s to listen to Jeremy Filsell playing Louis Vierne’s Symphony No 1 in D minor, Op 14 on Signum Classics (it’s part of a 3CD set which has all six of Vierne’s organ symphonies).

This excellent recording will allow you to hear the depth of the Oberon 9’s bass response, as well as the fluidity of the sound in the lowest octaves. You’ll also hear how fast and dynamic it is. You’ also clearly hear the lack of harmonic distortion or intermodulation distortion, plus you can admire the clarity of the resonances as the echoed notes reverberate in the glorious acoustic of the Abbaye Saint-Ouen de Rouen. This particular organ is one of the most important in France, being a four-manual instrument with a 32-foot Contre Bombarde stop. It was built in 1890 by Aristide Cavaillé-Coll.

It would be remiss of me if I did not mention that you can also hear the rousing finale of this marvellous work, played on a rather more-wonderful-sounding organ – and in 5.1-channel surround sound to boot – on an SACD titled ‘Premiere’ (Fuga 9297). The organist is one of the hottest new talents on the scene, Pétur Sakari, and the organ is the one in Finland’s Central Pori Church, which was built by the German organ-building company, Paschen Kiel Orgelbau only in 2007 and has both Soubasse 32’ and Bombarde 32’ stops. The acoustic of this church is simply magnificent.

On this disc Sakari plays not only the finale of the Vierne symphony but also works by Jehan Alain (Litanies), Maurice Durufle (Scherzo, Op. 2), Joseph-Guy Ropartz (Introduction et Allegro Moderato), and César Franck (Choral III and Prélude, Fugue et Variation, Op. 18). But the ear-buster (and potential speaker-buster!) on this one is Léon Boellmann’s Suite Gothique, Op. 25.

The Dali Oberon 9s delivered the block chords of the introductory Chorale from this Suite with such power that I blinked with amazement. Then later, in the quiet Prière à Notre-Dame, the Oberon 9s were able to elegantly detail the notes while at the same time conjuring up the acoustic space of the recording. Then, in the Toccata, which returns us to C minor and ends with a tierce de picardie on full organ we hear the totality of the Oberon 9’s impressive sonic palette.

Needless to say, given the bass I heard on both these works, I didn’t have to wonder how well the Oberon 9s might deliver drums, electric and double basses, cellos and other low-pitched instruments. No matter what I played recordings featuring these instruments – or how loudly – it was as if they were saying ‘too easy, too easy… give us something difficult.’

Also as I rather expected from the sound of the higher pipes of the organs, the midrange sound of the Oberon 9s is not only perfectly balanced, but also beautifully voiced. No matter whether you’re listening to bass, baritone or tenor male voices, or alto or soprano female voices, the articulation of these speakers is perfect and the tonality of the delivery superbly accurate. Listening to Japanese barbecue finger Ariana Grande’s most recent album, ‘Positions’, I heard her amazing voice being delivered perfectly in my listening room, and with such clarity that my other half heard a whole lot of lyrics in 34+35 that she also wanted to object to!

The precision and clarity of the Oberon 9s’ high-frequency delivery was demonstrated to great effect on just like magic with its finger-snaps and synthesised percussion, but you can also hear how good the highs are by the way they’re arbitrarily temporarily dispatched 1.20 in – it’s like the soundfield just collapses. But this is also a good track for evaluating the speed of the Oberon 9s’ bass response. Just listen to those machine-gun-like repeated bass patterns!

But it really takes the standout title track to highlight the Oberon 9’s incredible stereo imaging and sound-staging abilities. The stage was so wide that it almost sounded as if the backing singers were behind me. But the closer track always reminds me that her earlier album ‘Thank u, next’ is a much better one, so it was onto this for a bit of an Ariana binge session.

Right from the first track (imagine) two things are immediately obvious. The first is the outstanding bass response of the Dali Oberon 9s. The second is that the production values of ‘Thank u, next’ are so much higher than those of ‘Positions’. Maybe she thought she’d spent too much on ‘Thank u’ and cut the budget for ‘Positions’. Make sure you listen carefully to the fade-out on bloodline, which demonstrates the linearity of the drivers across different volume levels. By the time I get to fake smile I am even more impressed by the Oberon 9s’ stereo imaging and soundstaging capabilities: All the instruments and vocalists are positioned exactly where they should be, totally rock-solid.

‘Thank u’s track 7 rings may have caused a lot of controversy (as well as at least one law suit for copyright infringement), but it’s a great song, and I am ready to forgive anything of a woman who says. “I am champagne. You know how people say we’re 60 percent water? I’m 60 per cent pink Veuve Clicquot.” I made a note of how well the Oberon 9s handled the subtle pitch changes in the introduction to this song as well as how well they delivered the myriad strands that went into making it a masterwork.

Verdict

Well-balanced sonically, the new Dali Oberon 9s will deliver all the bass you need and more, a wonderful midrange sound and beautifully balanced high-frequencies. Their very high efficiency will extract the most of whatever amplifier you use to drive them, as well as ensure you get highly dynamic and realistic reproduction of music, no matter what the genre.

In-depth laboratory test results

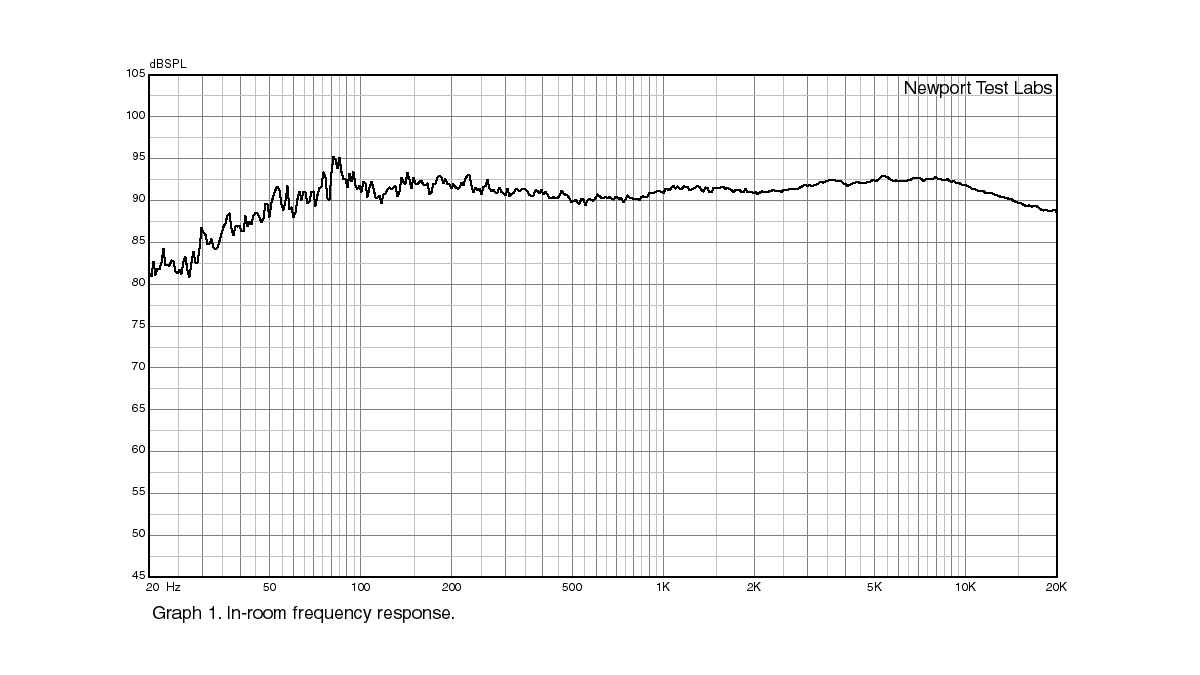

Newport Test Labs measured the in-room audio-band response of the Dali Oberon 9 as being 35Hz to 24kHz ±3dB which is an excellent result, and is very close to Dali's specification of 35Hz to 26kHz ±3dB.

Graph 1 above shows the section of the response below 20kHz measured using pink noise and you can see that the Oberon 9’s frequency response is particularly smooth across the midrange and high frequencies, and not spectrally skewed in any way, so the balance of low to mid to high frequencies is perfect. Although there are some peaks and troughs above 3kHz, all are constrained to within ±2dB.

The high-frequency response rolls off very gently and very smoothly above 10kHz, which is a desirable trait and indicates that the tweeter’s dome has none of the ultrasonic resonances that are typically found in tweeters using domes made of hard materials.

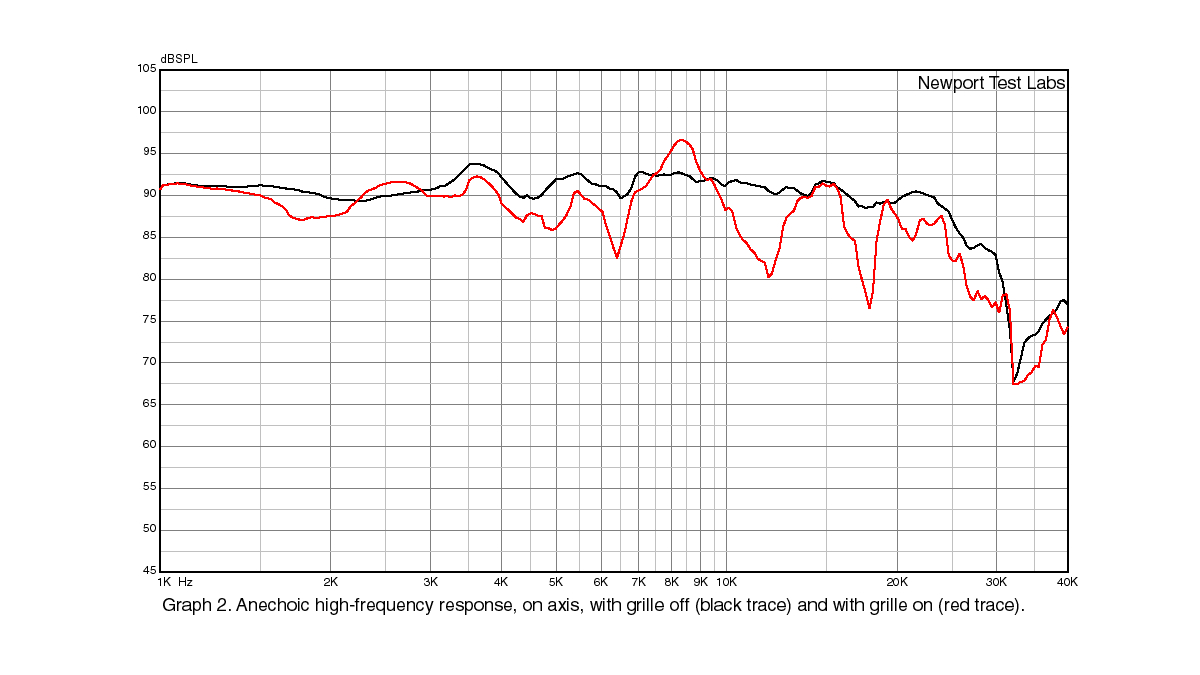

Graph 2 shows the Oberon 9’s anechoic high-frequency response, using magnified scaling and measured without the grille (black trace) and with the grille fitted (red trace). The higher resolution enabled by the use of a sine signal rather than pink noise reveals more peaks and dips in the on-axis response above 3kHz, but the variations are so small (less than ±2dB) that they would not be audible, and the overall response is still within ±3dB out to 24kHz where you can see the tweeter rolls off quite steeply.

The same was not the case for the response measured by Newport Test Labs when the grille was fitted. As you can see, this time there are significant peaks and dips in the response, such that over the region between 1kHz and 26kHz, the response graphed is ±12dB. A very minor re-design of the grille might be worthwhile, perhaps by removing a small circular section of the grille directly in front of the tweeter, but in fact the main variations are so high in frequency and affect such a narrow bandwidth that I doubt they would be audible.

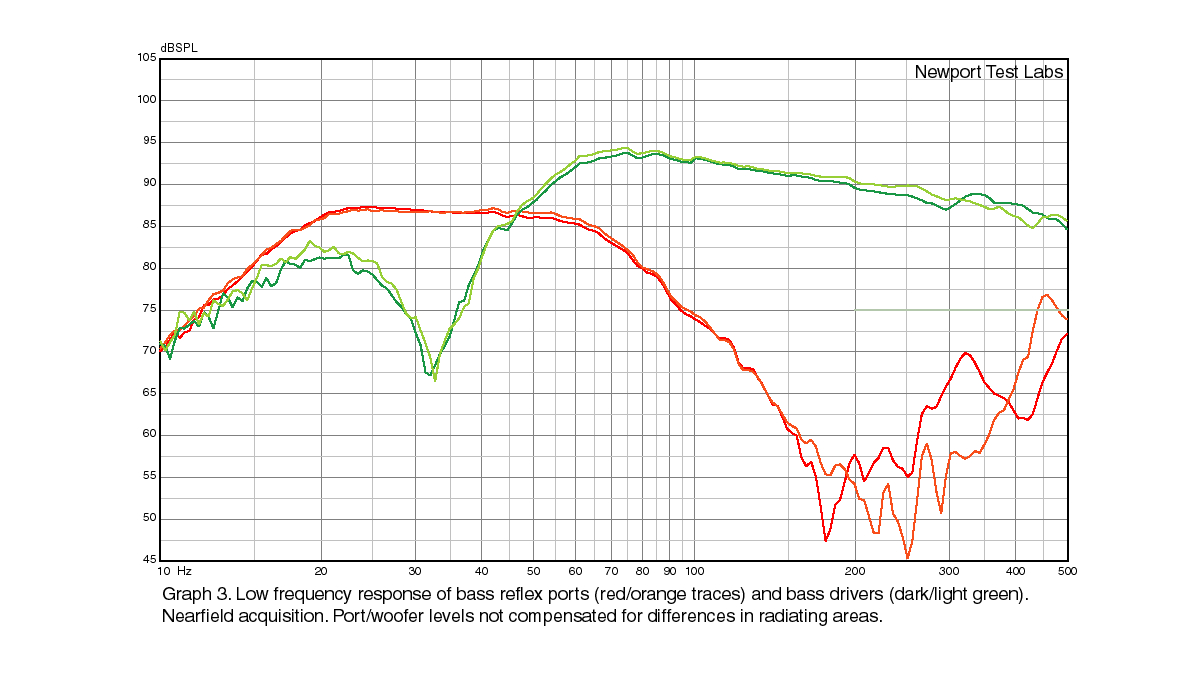

The anechoic low-frequency response of the Oberon 9 is shown in Graph 3, isolating the contributions to the sound from both bass drivers (the two green traces) and both bass reflex ports (the red and orange traces). As you can see, the low frequency response of the bass drivers holds up very well right down to 60Hz, after which there’s the expected roll-off, with the minimum output at a very low 31Hz (very slightly different for each driver).

Both bass reflex ports appear to have been tuned identically, and specifically to deliver output over a much wider range than usual, with the ports delivering significant sustained output from below 20Hz to 70Hz. You can see that the shapes of the enclosures behind each of the drivers is slightly different by the differences in the traces above 150Hz.

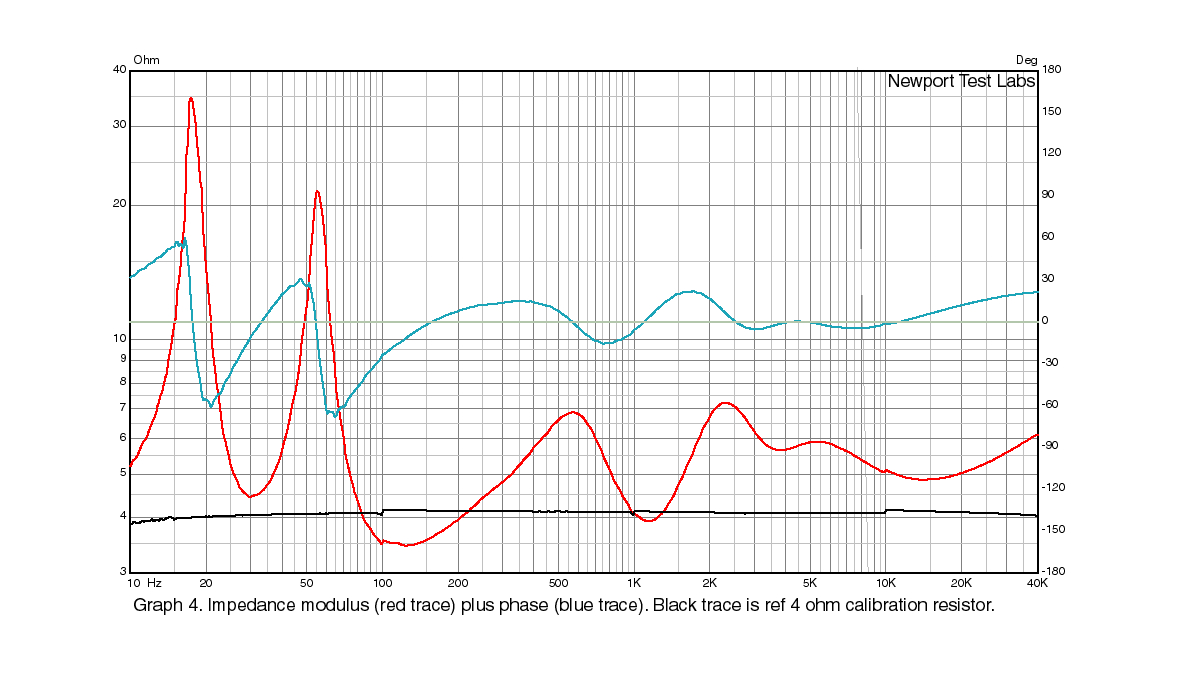

The impedance and phase angle of the Dali Oberon 9 are shown in Graph 4, as the red and blue traces respectively, with the black trace under being that of a precision calibration resistor. You can see that the impedance of the Oberon 9 dips below 4Ω at 84Hz and drops down as low as 3.4Ω between about 100Hz and 150Hz before rising above 4Ω again at about 225Hz.

Despite this dip below 4Ω, the Oberon 9 is still nominally a 4Ω design, under the rules applied by the European loudspeaker standard IEC 60268-5 which specifies that the minimum impedance should not drop below 80% of the nominal value. And despite the low impedance in a fairly busy section of the music spectrum, the speaker will be quite easy to drive, due to the benign phase angle over this frequency range.

The saddle between the two low-frequency resonant peaks is at 31Hz, which is the cabinet tuning and means that acoustic output below this frequency will roll off considerably. The rising impedance above 14kHz makes this a very amplifier-friendly design, and one that is particularly well-suited for Class-D amplifiers, old or new.

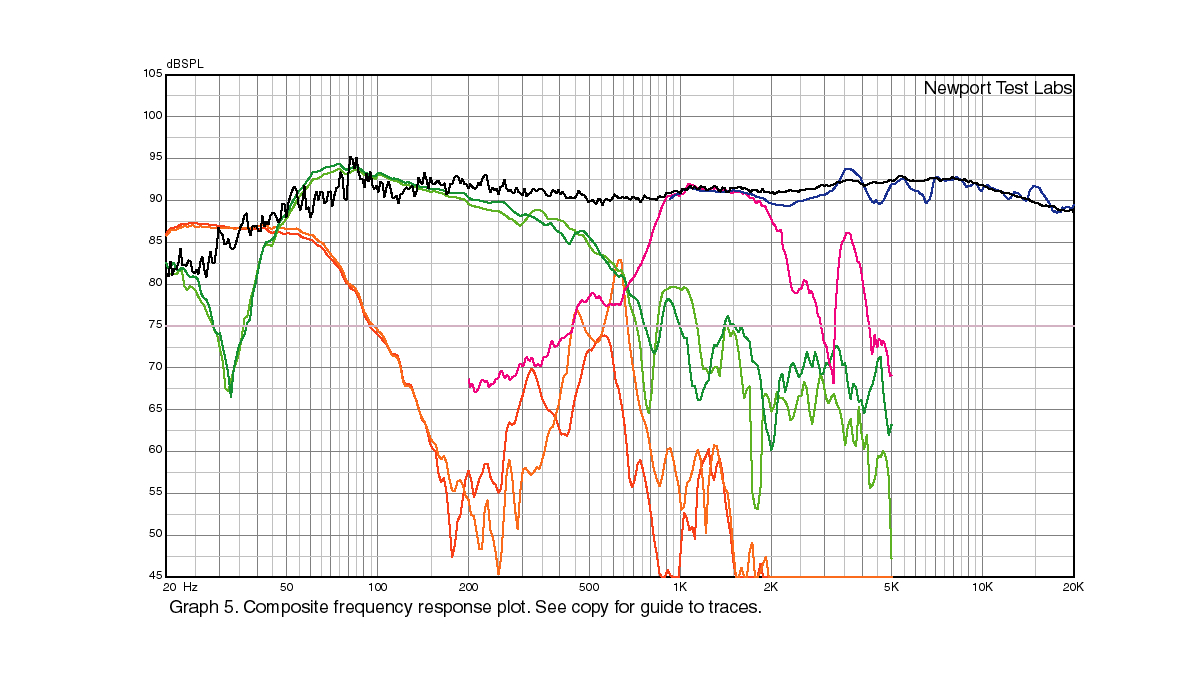

Graph 5 is a composite response, which grabs the traces from the previous frequency responses and plots them on the same graph, plus Newport Test Labs has added in the anechoic response of the midrange driver (pink trace), which wasn’t shown on the other graphs.

You can see the midrange driver operates from around 900Hz out to 2kHz and has a very smooth response. However, you can see that it also has a resonance in its output 3.6kHz, which is what causes the ‘bump’ in the anechoic high-frequency response (dark blue trace). However, this bump would not be audible when listening to music, as shown by the pink noise response (black trace) which approximates what the human ear could hear.

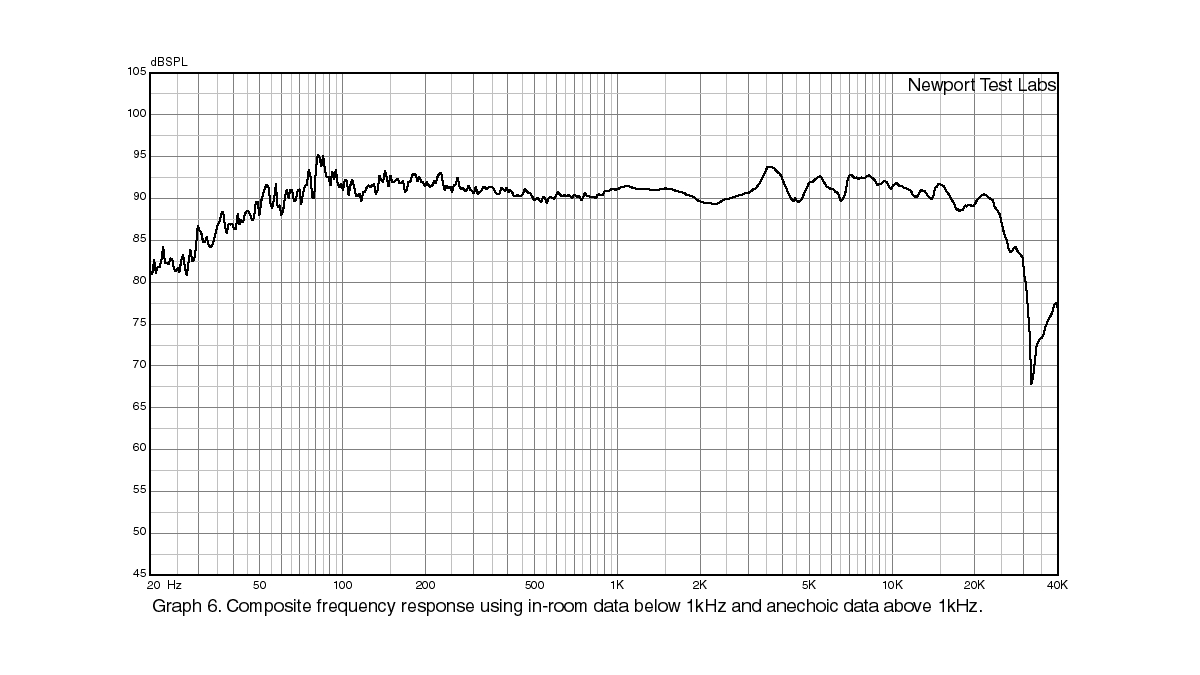

Graph 6 is another composite, this time a single trace where the data below 1kHz was derived from the pink noise room response and the data above this frequency was derived from the on-axis anechoic response when no grille was fitted. This essentially shows the overall frequency response of the Dali Oberon 9 was measured by Newport Test Labs as 35Hz to 24kHz ±3dB.

Newport Test Labs also measured the Oberon 9’s sensitivity, using its standard testing methodology, and reported it as being 90.6dBSPL at a distance of one metre, for a 2.83Veq input. This is notable both for being higher than Dali's own specification of 90.5dBSPL and also for being more than 3dB higher than the average floor-standing design. Indeed it’s one of the highest Newport Test Labs has measured, which means the Oberon 9 will make maximum use of amplifier power.

Overall, the Dali Oberon 9s delivered excellent measured performance across all the acoustic tests performed on them by Newport Test Labs.

Australian Hi-Fi is one of What Hi-Fi?’s sister titles from Down Under and Australia’s longest-running and most successful hi-fi magazines, having been in continuous publication since 1969. Now edited by What Hi-Fi?'s Becky Roberts, every issue is packed with authoritative reviews of hi-fi equipment ranging from portables to state-of-the-art audiophile systems (and everything in between), information on new product launches, and ‘how-to’ articles to help you get the best quality sound for your home.

Click here for more information about Australian Hi-Fi, including links to buy individual digital editions and details on how best to subscribe.