Music quality is the worst it’s been since the dawn of hi-fi - and it’s not even One Direction’s fault.

On the one hand, music has never been so easily available: downloading and streaming has given us access to more new bands, artists and recordings than have ever been within reach before, at home and wherever we go.

On the other hand, the overall fidelity of the stuff we’re listening to has dropped through the floor. The ‘lossy’ formats that have enabled the digital music revolution - MP3, AAC, OGG and others - are compromised as a matter of structure. In order to facilitate quick downloading and on-the-go streaming, they take a 1411kbps CD-quality source file and take out data until it until it’s a quarter (320kbps), an eighth (160kbps) or even a twelfth (128kbps) of its original size.

Given the scale of the butchery, these formats work well. But as any audiophile will tell you, it’s easy to tell the difference between the original CD version of a track and a lossy copy of it - and the difference is rarely for the better. You lose detail and dynamics; instruments sound less defined, vocals less natural.

In short, we’ve embraced worse-sounding music in order to have access to more of it.

Now for the good news. The technological limitations that made lossy music formats necessary have melted away. We now have the space to store high-quality music, and the pipework to stream and download it.

Connectivity and infrastructure has evolved to the point that the sky is the limit. Lossy formats are no longer necessary, but we needn’t top out with that 1411kbps file either. We can embrace higher-resolution digital audio than ever - and that’s where Hi-Res Audio comes in.

What Hi-Res Audio is

Hi-Res Audio, or HRA for short, is audio of a resolution higher than that of CD. The 1411kbps files that constitute CD quality are the result of compression process that samples the left and right channels of the original recording 44,100 times every second (44.1kHz), and captures the samples as digital snippets 16 bits in size.

Play with either of those numbers and you change the resolution of the file. The more samples every second, the finer the slices of the original recording you’re capturing. The higher the bit depth, the more information each one of those slices contains.

HRA makes both numbers significantly bigger. Sampling occurs at a rate of at least 96,000 times per second (96kHz, though 192kHz is also common) and the samples are normally recorded in 24 bits. Everything else being equal, the more data captured, the closer you get to the original recording.

The numbers stack up...

HRA means big files, often exceeding 200MB per four-minute, 24-bit/192kHz song. But 200MB is no issue for a modern UK broadband connection, which will download it in just over a minute. It’s even possible to stream two files of this quality over the average UK 4G connection at the same time (although you’d better watch your data allowance). A 4TB external hard drive capable of storing over 20,000 HRA songs will set you back less than £90.

That’s not all. A new format, MQA, will in theory provide an even better experience than HRA in files of similar size to CD. This is achieved by a process called ‘encapsulation’ that ‘folds’ all of the music’s essential timing data in on itself. Its cleverest characteristic is its ability to play on anything that can handle WAV, FLAC, ALAC and other lossless audio files - and it’ll sound even better on MQA-certified ones.

However you cut it, MP3-trouncing audio is now trivial to stream, download and store.

...and the hardware’s ready

Many smartphones, including the LG G4, Sony Xperia Z5 and Samsung Galaxy S6, will play the formats (typically FLAC) and resolutions of HRA at full quality off the shelf. Lightning port-equipped iPhones are capable of playback, too, with the right external DAC (Onkyo’s DAC-HA-300, say) and a suitable music app (such as Onkyo’s HF Player). Want a standalone player like the old days? Try the Astell & Kern AK Jr or Sony NW-ZX2.

There are headphones certified and tuned to deliver the extended bandwidth of HRA, too. Philips’ Fidelio M1 MkII carries the logo, and Onkyo has a set suitable for most tastes, from the current wired in-ear E900 to the soon-to-be-launched over-ear H900M and open-back A800. All are HRA-certified, thanks to their ability to reproduce sounds most headphones can’t.

Any recent laptop is capable of HRA playback, although some will benefit from the use of an external DAC such as the Audioquest Dragonfly, Onkyo DAC-HA300 or Oppo HA-2.

If you want to add HRA-streaming capability to your hi-fi, separate network streamers like Naim’s ND5 XS and combined CD players/streamers such as Onkyo’s C-N7050 are two of myriad available options. Bluesound and Yamaha have multi-room HRA covered, while Onkyo’s Bluetooth-equipped X9 speaker will play HRA from your PC via its USB connection.

What about the music?

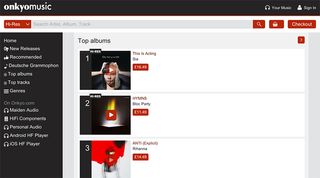

HRA isn’t just for hi-fi addicts. There’s a wealth of brilliant, popular music available to download in better-than-CD quality from services including 7Digital, HDTracks, Qobuz (which also offers HRA streams), Onkyo Music (which already stocks MQA) and more.

A quick glance at recent HRA releases reveals Blackstar, the latest David Bowie album, alongside new records from Bloc Party, Iron Maiden, Sia and Suede, as well as much of Deutsche Grammofon’s extensive archive. The pieces are all in place: the hardware, the music and the technology to bring the two together. Now is most definitely the time to embrace Hi-Res Audio - you deserve it.

Sign up for an exclusive Onkyo Hi-Res Audio demo at the Bristol Sound & Vision show

Are you going to the Bristol show? Want to get ears-on with Onkyo's new hi-res range? We're offering a series of exclusive product demos on Friday 26 February, the first day of the show. Spaces are limited - sign up here to avoid disappointment.