Philips: flogging off the family silver? No, just going back to where the Philips brothers started

The recent kerfuffle about the announcement that Philips is to sell off its audio, video and multimedia businesses, effectively quitting the consumer electronics business, couldn't help but raise a wry smile.

For every person commenting that it was the end of the world as they know it, there was one saying they hadn't bought anything Philips for years.

And for every one saying it was no loss as their TVs were rubbish – thus totally missing the point – , someone else popped up to praise the quality of the set they'd bought.

At least we were spared the xenophobic rants about 'never wanting to buy any of that Chinese-made tat' or 'the Chinese stealing all our jobs', not least because the company taking over the last of the Philips consumer electronics lines is Japanese.

Mind you, there's no clear indication where Funai – the Japanese company in question – will be making the new Philips-branded products, while such thinking also overlooks the fact that Philips has been making its consumer electronics in Far Eastern countries for a long time.

Chances are Funai, which now has a licence to market consumer electronics products under the Philips brand worldwide, will be making its products in China, where it already has its own factories.

This is, after all, the company behind North American Philips TVs – and Philips sub-brand Magnavox models – for the past five years: in 2008 it signed a seven-year contract with Philips for the brands, and last year added the Dutch company's audio products to its Stateside portfolio.

Get the What Hi-Fi? Newsletter

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

Also worth noting is that Philips has been easing away from the consumer electronics business for some time: since last year its TVs for most of the world have been made and sold by a joint venture with Chinese company TP Technology called TP Vision. Philips is very much the minority partner in this operation, with TP holding a 70% stake.

Philips: just doing what others are thinking

But while most of us may be more familiar with Philips as the inventor of the compact cassette, the co-developer of the CD and the originator of the 21:9 TV, what the company is now doing – pulling out of the audio-visual business to concentrate on more profitable sectors – is something at least some other big companies are either doing, or considering.

Panasonic president Kazuhiro Tsuga has already put in motion restructuring plans aimed at reducing the company's dependence on the volatile TV market, and concentrate more on sectors such as solar and other renewable energy sources, home fuel cells and energy-saving, and industrial products.

As Tsuga said at CES 2013 back at the beginning of this yesr, 'Panasonic's future is being built on far more than a single product category and its contribution to people's lives is extending far beyond the living room.

'We are focusing our business activities on four broad areas in which we impact people's lives — residential, non-residential, personal and mobility. With people, who unite them, at the centre of all our activities, we want to add value to customers' lives wherever they are.'

Similarly Sony, in its effort to strengthen ties with Olympus, has its eye not on the beleaguered Japanese company's camera operations, but its optical products for medical and industrial uses.

And moreover what Philips is now doing – leaving itself with two main divisions, Lighting and Healthcare – is going back to where it started: founded in 1891 as a manufacturer of lightbulbs, it later diversified into valves, as part of its work on early radio technology in its first research laboratory.

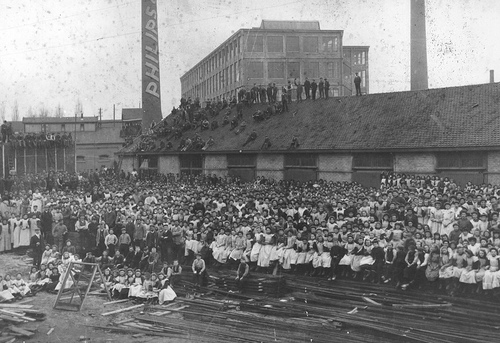

At its start, what is now Koninklijke Philips Electronics N.V. ('Koninklijke' literally means 'king-like' in Dutch, and is a title given to esteemed companies by the King or Queen of the Netherlands) was a family company, founded by Gerard Philips and his banker father Frederik, who put up the money to buy an empty factory in Eindhoven (above)to make carbon-filament lightbulbs.

As an aside, industrialist and financier Frederik's cousin was Karl Marx!

The Philips brothers: Anton Frederik (left) and Gerard

By 1907, after some financial struggles, father and son had founded Philips Metaalgloeilampfabriek N.V. (Philips Metal Filament Lamp Factory) and in 1912, with the addition of Gerard's younger brother Anton to the company, the company became Philips Gloeilampenfabrieken N.V. (Philips Lightbulb Factory).

'Everybody say "Kaas" ': the Philips staff in 1910

This is the first tube it made, in 1913, and the manufacture of valves started in earnest in the early 1920s, as part of the expansion of the business beyond lighting.

So where does the medical bit come in? Well, with its work on valves, it found itself being asked to supply spares and repairs for the X-ray machines, which had been developing since the last years of the 19th century. In 1927 Philips bought a German X-ray tube manufacturer, and was starting to build up its medical equipment operations based around its radio knowledge.

In 2012 its Healthcare operations, having diversified into fields such as MRI scanners (above), ultrasound, nuclear medicine and the portable defibrillators found on trains, planes and workplaces, had sales of €9.96bn (£8.6bn), making it the largest of the company's three major divisions.

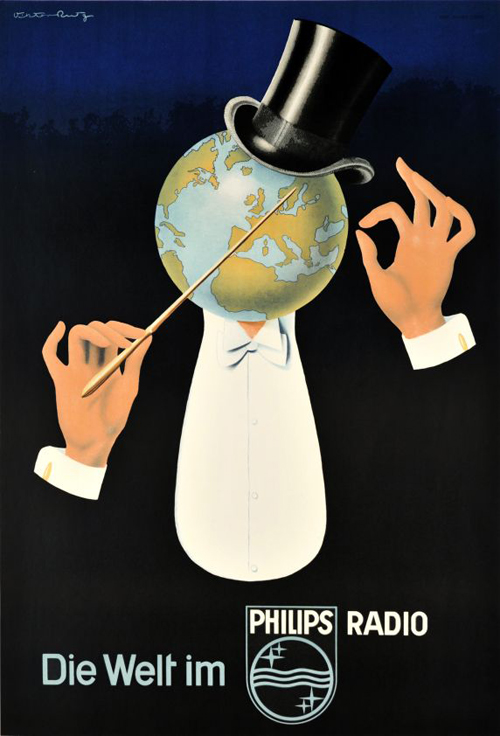

Between the 1920s and last week's announcement, Philips has of course been most familiar to the majority of consumers for its products in TV, audio and video, and rather than lay out a formal history of the company's achievements in these sectors, it's perhaps more illumination just to take an overview through some significant products (oh, and have a giggle at some contemporary adverts).

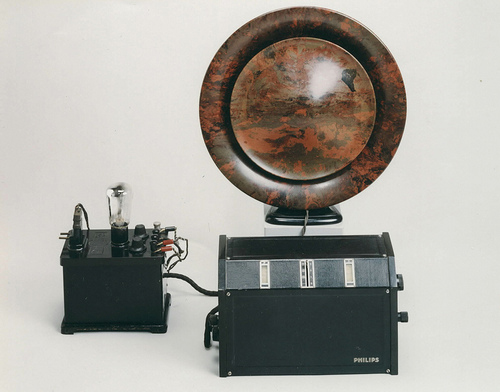

In 1927, as well as getting into the radiography business, Philips was also getting into radio, not only launching its own radio receiver (above), but also a shortwave radio station called PCJJ, initially to broadcast to what was then the Dutch East Indies.

Queen Wilhelmina used the service on June 1st, 1927 to speak to her people in what would later become Indonesia.

Two years later PCI was set up as a dedicated Dutch service for the East Indies, PCJJ by then having delivered on its lofty ambition of broadcasting in a range of European languages worldwide, thus becoming the foundation of the radio service on behalf of the League of Nations, which eventually set up its own transmitters.

PCJ calling: 60kW of water cooled valve power and steerable antennae

Hilversum calling

1933 saw the stations moving from the Philips experimental station in Amsterdam to studios in Hilversum, a name as familiar from the dials of old radios as Droitwich and Luxembourg, and by 1936 the power had been cranked up to 60kW, thanks to a transmitter powered by fearsome-looking water-cooled valves, making it the strongest shortwave transmitter in Europe.

As if that wasn't enough, in 1937 a pair of 60m towers topped with rotatable antennae were installed at the transmitter park in Hulzen, enabling PCJ, as it had now become, to steer its signal wherever transmissions were required.

PCJ remained on air until the transmitters were seized by the invading German army in 1940 and repurposed for propaganda purposes, and after the war PCJ and PCI were taken over by the Dutch government, becoming Radio Netherlands Worldwide.

On the receiver side, Philips moved things on pretty rapidly, with the complex early sets giving way to more home-friendly designs such as the classic 'Chapel' radio (left).

It came complete with the Philips logo of stars and radio waves adorning the speaker grille, just as it had dominated the design of the company's separate speaker for earlier radio sets.

That speaker, like earlier models, was made from Philite, Philips being the first company in the Netherlands able to process the early plastic, Bakelite, developed at the beginning of the 20th century.

The company had invested heavily in Philite, building a purpose-designed factory to make mouldings in 1929, where Frits Philips, the son of founder. had his start in the company. We'll come back to both Anton and Frits a bit later…

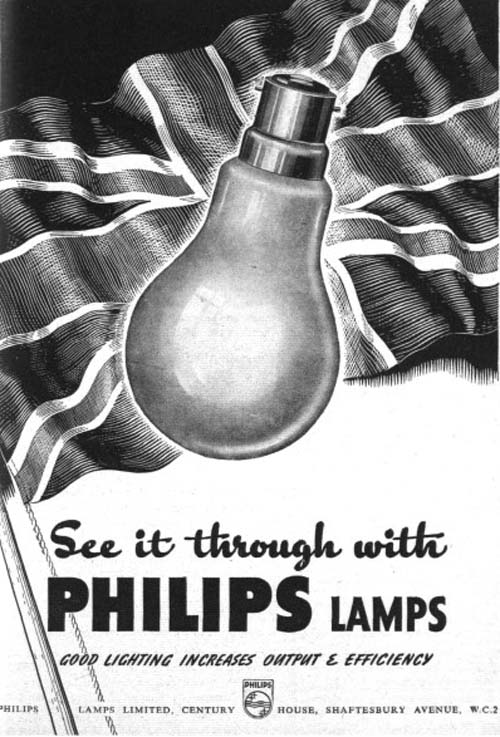

Radios have been a major part of the Philips business for almost a century – even during WWII it was promoting its radios back home, and lightbulbs in the UK market with this patriotic advert.

Not long after the war the company moved from valves to the new transistors, having worked closely with the Bell Labs inventors of the technology.

In 1949, just two years after the invention, Philips made its first transistor, launching a germanium diode soon after: by 1953-54 the Philips board had built a large semiconductor factor in Holland, and its first commercial transistors were on sale, under familiar names in various countries, such as Mullard in the UK and Amperex in the States.

And the company promoted these new radios for use everywhere, as transistor sets gradually replaced hefty, and expensive, portables such as these it was selling in 1954. That 6-Valve Portable, by the way, would be just under £1000 in modern terms.

Suddenly radios became go-anywhere, not least in the car, where the idea of music on the move had been established since before WWII, but took on new glamour in the 1950s.

And if the idea worked once, why not try it again to promote the line-fitting of Philips radios in Renault cars?

In time, radios would become even smaller, and then bigger again, as new features such as built-in cassette decks were fitted: shown left is one of the first, and it does look rather like a radio with the company's original cassette recorder bolted on the top.

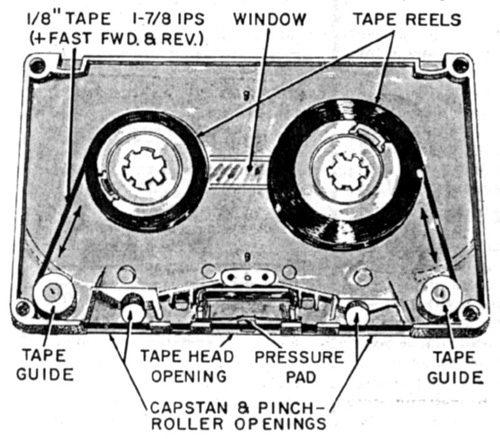

Ah yes, cassette – or to be more correct the Compact Cassette.

From dictation to 'Killing Music'

With the launch of the first machines in 1963, originally as a means of voice recording, for example for dictation – hence the start/pause switch on the microphone – Philips took home recording out of the enthusiast arena of open reels and head-adjustment, and into a drop-in format anyone could use.

Encapsulated in their plastic shell, the tapes could be carried around, swapped and so on – and thus began a generation sitting with microphone pressed up to the speaker of radio or TV, recording Pick of the Pops, Round the Horne, The Old Grey Whistle Test or whatever.

(Well, I had one of the first recorders, complete with T-bar main control, and that's just what I used it for once the novelty of recording friends and family had worn off.)

The record industry, of which Philips was a part, was less convinced, eventually leading to the Home Taping is Killing Music campaign – in fact it didn't, though less interesting music threatened to do the job instead.

Meanwhile in the early days of cassette, Philips was keen to create an image for the new system beyond the simple dictation function: here's a German ad with a reporter doing a pit-lane interview, complete with what looks like his old college scarf and of course a decorative female.

Meanwhile in the USA the company went for a more factual approach:

Incidentally, why the Norelco name? Well, in the 1940s US company Philco – originally the Philadelphia Storage Battery Company, but by then the biggest radio manufacturer in the USA – got Philips banned from using its own name in the States, suggesting (in the way only lawyers can) that confusion would ensue.

Hence was born Norelco: the North American Philips [electrical] Company. Later on, in the 1970s, Philips bought the Magnavox company and used that name on its US consumer electronics, but kept Norelco for its other products.

In 1961, Philco had been bought by Ford, going on to design and build all of the control consoles for the NASA space programs from the Mercury launches of the 1960s right through to the Space Shuttles, not to mention supplying in-car entertainment for generations of Ford vehicles.

In 1981 the name was bought again: this time by Philips, so it could at last use its own brand on its own products in the USA.

The Marantz years

On the subject of brands owned by Philips, for over two decades the Dutch company was the owner of Marantz, and getting a first listen to new products meant a trip to a building on the Philips 'campus' also housing the parent's consumer electronics operations.

Founded in America in 1952 by Saul Marantz, the company had been bought by Superscope in 1964, which in 1966 started making products in Japan with a company called Standard Radio, which later changed its name to Marantz Japan.

A manufacturing plant was set up in Belgium in 1974, and in 1980 almost all the Marantz operations – brand and overseas assets – were sold to Phlips. However, Superscope kept hold of the US brand and operations.

It would be another 12 years before Philips managed to acquire those.

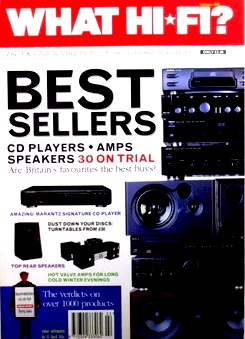

The period under the Philips ownership produced some of the best-known Marantz products of recent times, not least the CD-63KI CD player (above) – or, to give it its correct designation, the CD-63MkII Ken Ishiwata Signature.

The idea of taking a standard player and hotrodding it to create a 'Signature' giant-killer, reflecting the individual sonic taste of one person, was hatched between Ken Ishiwata and Terrie O'Connell, now President of European Sales & Market for current Marantz parent D+M Group.

And it took shape in a taxi stuck in Tokyo traffic on the way to the old Tokyo Audio Fair, some time around the mid-1990s.

How do I know? Well, I happen to have been in the taxi at the time!

Their plan was to take the established Marantz 'Special Edition' idea of tuning an established player by taking it apart, retrofitting it with more upmarket components and making it a 'Signature' version, giving buyers a sense of the personality behind the sound.

The KI idea soon caught on. We featured the 'Sensational Marantz Signature CD player' on the cover of the magazine in February 1996, and the technique went on to be applied to a number of Marantz amplifiers and CD players over time.

Ishiwata travelled the world to promote the products, and the brand as a whole, as the company's 'Brand Ambassador' – and he's still racking up the frequent flyer miles to this day.

All the KI products came with a certificate signed by Ishiwata, but there's a way to tell the very earliest ones from the later models: with the company not sure how well the idea would fly, the first KI models came with a plastic 'script' badge.

Only when the line became established was this replaced with the rectangular metal plate with the KI Signature logo engraved on it you can see on the player at the top of this section.

The KI Signature project was symptomatic of the fact that, although Marantz was part of Philips, both in corporate terms and physically, there were 'Marantz people' and 'Philips people', so it was no surprise when, in 1997, Marantz Japan bought the brand and all the overseas sales companies from Philips.

The following year Marantz merged with Denon to form D&M Holdings, in which Philips still held an interest, but in 2008 the Dutch company sold its remaining stake, severing all ties with Marantz after nearly three decades.

Time for a new cassette – and this one's digital!

By the beginning of the 1990s, when it came to replace the cassette – well, clearly someone thought it was time – Philips partnered with Panasonic/Technics parent company Matsushita to develop the Digital Compact Cassette.

Just like a cassette, but digital, so obviously better, wasn't it? – and back-compatible with existing tapes, which you could play in the new DCC decks.

The usual Philips partner-in-crime, Sony – with whom it had developed CD and its various spin-offs – was washing its hair that night, hence the Matsushita tie-up.

Well, actually Sony was developing its own cassette replacement, the magneto-optical MiniDisc, and before long we had a full EastEnders-style 'But I fought you was faairmly!' format war on out hands.

Philips went out on the road with Dire Straits to promote DCC, as it had with CD, while Sony staged a number of press events including the famous one where a senior bod held up a MiniDisc portable in front of a packed auditorium, plugged it into the PA system, and music surged forth.

Trouble is, it continued to surge forth even when the jack-plug fell out.

In time, both formats vanished from the consumer world, even though I am sure somewhere in my garden shed is an unused DCC portable and mains deck, each with my name on an engraved plate. Nice try (and nice trip), Matsushita!

However, though MD did carry on in some professional applications, these days they are just about forgotten,

It's just that DCC is probably a bit more forgotten than MD, Philips having canned it just four years after its 1992 launch and conceded the fight to Sony.

The start of audio compression

What both systems did introduce us to was the idea of audio compression, in order to reduce the amount of data needed to store a piece of music. Philips had PASC (Precision Adaptive Sub-band Coding), giving a 4:1 reduction, while ATRAC – Sony's Adaptive Transform Acoustic Coding, developed from the company's Sony Dynamic Digital Sound cinema system – did nearly 5:1.

Each claimed its system sounded better; each said it was all but impossible to hear the difference between the data-reduced version and standard CD. Sound familiar…?

By the way, I covered the Philips CD story in my piece last October to mark the 30th anniversary of the launch of the silver, which you can read here. It's enough here to mark the fact that the company was also one of the leading lights in the development of SACD – which was another one of those 'time for a replacament' exercises.

Below is the company's imposing prototype SACD machine, the SCD2000.

Also worth noting that for a long time Philips was quite a player in the hi-fi components market, and not just with sources such as CD and cassette.

It also developed the 'way ahead of their time' Motional Feedback speakers, using sensors in the bass unit to feed back information to the amplifier, which then adjusted itself to control the low-end stuff more accurately: you can see the sensors under the dustcap in this cutaway shot.

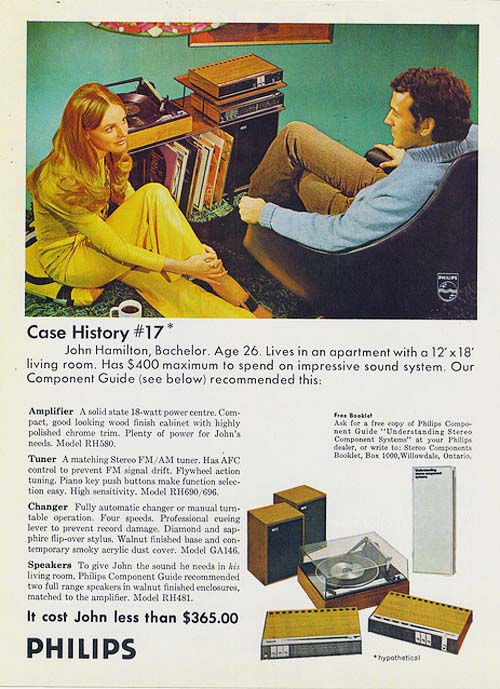

Mind you, that didn't stop it promoting some products with what are now fairly cringeworthy ads, such as this one from an American magazine in 1970.

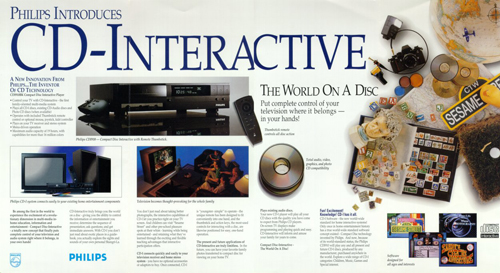

Oh, and let's quickly draw a veil over the company's invention of CDi, an interactive version of the compact disc able to play games, show movies, add video to music and so on.

Sounds like the precursor of today's DVDs and Blu-rays? Clearly you weren't there...

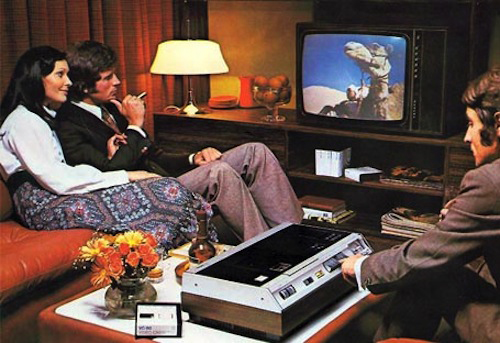

Meanwhiile back to recording, and Philips – having been involved in television since 1949, launched a home video recorder, the N1500 (above), into the European market in 1972, and quite a monster it was.

Clunks, whirrs and alarm clocks

My school had a couple of the early ones, used for recording educational programmes, back in the 1970s, and they clunked, whirred and grated, had a funny alarm clock on the front to set timer recordings which were initially limited by the 30-minute tapes we had, and were forever freezing or just plain stopping.

These days I have a machine at home capable of making a similar noise to an N1500 loading up a tape – but it only does it while grinding the beans.

It was all some way from the picture of domestic cool Philips ads of the time painted for the machine, and though the company eventually upped the running time to two hours – a whole movie on one tape! – the onslaught from Sony's Betamax and the JVC-developed VHS proved too much.

Or maybe V2000?

Philips fought a rearguard action with the V2000 system, launched in 1979 with a tape you could turn over just like an audio cassette to extend the running time to up to eight hours – the format was even called Video Compact Cassette – , but while there was a format battle to be won, the Dutch company wasn't in the fight.

Video 2000 was only sold in a few markets, and had gone by 1988.

That's been a recurring theme at Philips: some great ideas go on to be world standards, while others cost the company a lot of money, make a lot of noise, but have very little true impact.

After all, this is the company that introduced colour TV to Holland in 1964, three years ahead of widespread transmissions in Europe, formed a joint venture (since dissolved) with LG to make flat-panel displays, and in 2006 was able to trumpet the manufacture of the millionth TV using its Ambilight background lighting system at its plant in Bruges, Belgium.

Launched in 2004, Ambilight is designed to 'create ambiance, stimulate more relaxed viewing and improve perceived picture detail, contrast and colour' by using adaptive lighting to wash the wall on which the TV is mounted with coloured illumination complementing the on-screen image.

While still a Philips feature, it's not exactly the world's most widely-copied TV technology.

The same goes for the Philips concept of Cinema 21:9 TV, stretching the screen out to a wider shape to allow movies to be viewed without black bars top and bottom.

The system was launched in 2009 with a 56in model, rolled out in the USA in 2011, and had some huge money spent on promotion.

But even adding 3D couldn't save it: development and production stopped last year, Cinema 21:9 having failed to make any kind of dent in the market.

Educating the consumer

You sometimes get the impression that Philips hasn't just been about making products, but has set itself the task of educating consumers, like a benevolent uncle passing on its learning and experience to new generations.

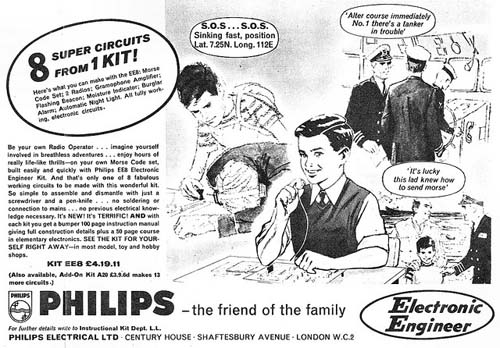

That certainly informed products such as this 1960s Electronic Engineer kit, which allowed any well-groomed lad whose parents could fork out a fiver – the equivalent of just over £80 in modern terms – not only to build their own radio set, but also use it help save those in peril on the sea.

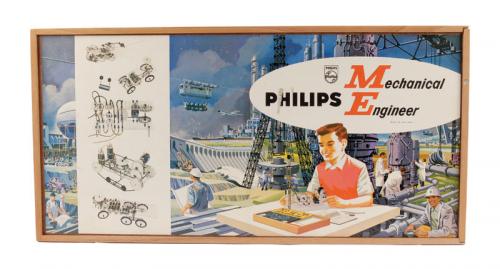

Philips was also keen to educate those with an interest in mechanical engineering, producing the set above around the same time. It provided all the metalwork, fasteners, gears, belts and pulleys required to allow the same lad – or at least his ginger-haired cousin – to build everything from cars and trains to box-girder bridges and cranes.

In fact, there was a range of Electrical, Mechanical and Radio Engineer sets sold by Philips at this time, both under its own brand and using the Norelco name in the States.

And education is where we come back to Frederik 'Frits' Philips, who started with the company in 1930, kept it going through the German occupation (during which time he was interned in a concentration camp for several months and saved hundreds of Jewish Philips workers from an even worse fate), and in 1961 became its chairman.

With the 75th anniversary of the company approaching in 1966, Frits decided to do something to mark the event, and decided it should be an educational resource for the people of Eindhoven, which is very much Philips Central.

Evoluon

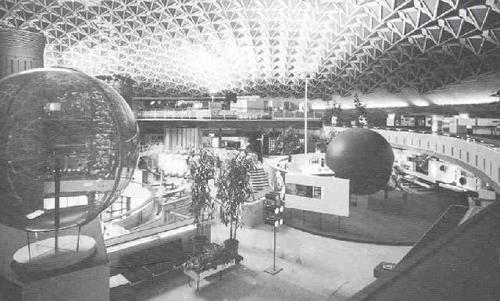

The result was Evoluon, the flying saucer shaped scence museum and educational centre that's become an Eindhoven landmark, and which was originally literally sketched out on a paper napkin by Frits Philips and a company designer.

Above is a shot of the interior when it opened, and below is Frits himself, on the right, showing an exhibit to a pipe-smoking Prins Bernard of the Netherlands at the official opening

Readers of a certain age may well be thinking 'Hang on – how do I know about Evoluon?', to which the answer is the impressionist film about it made by Bert Haanstra, which was in heavy rotation as a colour TV test-film on the BBC in the late 60s and early 70s.

Visitors entered using punch-cards, and could be guided round the exhibits with an audio commentary, using the splendidly-named Gidofoon.

And among the audio exhibits were these booths, where you could enjoy music in surround sound coming at you from all directions. Now there's an idea...

The first time I went to Eindhoven as a fairly new journalist getting on for 30 years ago, I remember sitting bored on a bus on the way to a press conference and suddenly gasping when I saw 'the mad building from the TV all those years ago' appearing through the window.

I was instantly carried back to primary school summer holidays, when rainy days were spent not getting soaked splashing in puddles, but soaking up everything the new colour TV could deliver.

Sadly, and despite pleading, I never got to go inside – there never seemed to be time in the schedule, I was told – and by the late 1980s Evoluon was in decline as a museum, closing to the public in 1989, and becoming a private 'invitation-only' Philips showcase before finally closing in 1998.

It's since been reopened as a conference venue, but Frits Philips harboured a wish to return it to its original purpose right up to his death, aged 100, in 2005.

His centenary had been marked earlier that year, appropriately with by a light parade in Eindhoven – oh, and just about everything in Eindhoven (including the city) being renamed Frits Philips for a day. On April 16, 2005, Eindhoven was Frits Philips Stadt.

So Frits Philips airport, station – they even changed the roadsigns for Meneer Frits (or Mr Frits), as he was known in Eindhoven.

Supporting the works team

Even in his final year Frits still went to see matches played by the company football club founded by his father, Anton, in 1913.

Philips Sport Vereniging – the Philips Sport Union – was set up to mark the centenary of the Dutch victory over the French in the Napoleonic wars.

The company built the Philips Sportpark, capacity 300, to house home games, and the club's original badge features a prominent lighbulb.

The same ground, now called the Philips Stadion (though it became Frits Philips Stadion for one day in 2005), kept its tiny capacity until the 1930s, rising to 18,000 in the 1940s and more than double that today.

When he went to see his team play, Frits Philips didn't sit in a director's box: instead he took the same seat in the midst of the crowd for every game, reflecting his lifelong dealing with workers and management alike.

On the day he died, his team won its match, and after his death it was decided his seat should always remain empty in his memory.

That win on the night of his death? 2-0, at home, against Fenebahce, Champions League.

Which is why, if you ever go to see a PSV Eindhoven home game, even if there's a capacity crowd, seat 43 in row 22 of section D will always be vacant.

Written by Andrew Everard

Andrew has written about audio and video products for the past 20+ years, and been a consumer journalist for more than 30 years, starting his career on camera magazines. Andrew has contributed to titles including What Hi-Fi?, Gramophone, Jazzwise and Hi-Fi Critic, Hi-Fi News & Record Review and Hi-Fi Choice. I’ve also written for a number of non-specialist and overseas magazines.