High-resolution audio: clarity or confusion?

Earlier today I was asked to write an article for another website on high-resolution audio. The brief was simple enough: what is high-res audio, how do I get it, why do I need it and what should I listen to it on?

But that got me thinking – there's nothing simple about high-res audio at all. In fact, quite the opposite. To the lay consumer, it must be utterly baffling. Last week's attempt by a number of consumer electronics bodies and record labels to come up with a formal definition for high-resolution audio only piled on the confusion.

Comments from readers of whathifi.com ranged from the bemused to the angry. What particularly upset them – and in my view with good reason – was one of the four descriptions issued to 'define' high-res audio: MQ-C, that's to say music taken from a CD master source (44.1kHz/16-bit), then 'upsampled' to higher resolution. Is that really proper high-resolution audio? I don't think so.

MORE: High-resolution audio – everything you need to know

It took me back to the 'High-Res Audio Experience' at CES in January. There was much hype about the event beforehand, an attempt by the CEA in America to make us adopt the phrase Hi-Res Audio, but the subsequent press launch I attended was a distinctly underwhelming affair that did little to clarify what's going on. HDTracks again promised to launch in the UK, but (as in previous years) has so far failed to do so.

MORE: Could 2014 be the year that high-res audio goes mainstream?

Then there's the issue of hardware compatibility. Not all audio equipment can play all high-res audio formats, so buyer beware. I have a Sonos system at home, but the best it can handle is CD-quality 44.1kHz/16-bit music streamed from Qobuz. Sonos doesn't handle full-fat high-res music, and there don't seem to be any plans on the horizon to enable it to do so.

Get the What Hi-Fi? Newsletter

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

To listen to high-res music, I need another system. As I sit at my desk writing this, on my iMac, the computer's hard drive is full of high-res music files from the likes of HDTracks, Linn Records, Naim and B&W's Society of Sound.

To play them I have to open TwonkyMediaServer on my hard drive, then search for the tracks from my iMac on the Pioneer N-30 network audio player plugged into my hi-fi system. As for high-res music discs, I also own a mix of SACD (Super Audio CD) and DVD-Audio discs, but no longer have anything to play them on, so they're gathering dust on the shelf above my desk.

BLOG: High-resolution audio – the science behind the numbers

In reality, not everyone has a hard drive full of high-res music files. As disc-based media gives way to streaming and downloads, millions of people use services such as Spotify, but only Premium subscribers get the 'Extreme' service, and that tops out at 320kbps in the Ogg Vorbis format. And iTunes, at best, is 250kbps in AAC (Apple Lossless) format.

'Proper' high-resolution music is considered to be at least above CD spec (16-bit/44.1kHz) and beyond that you can go to 24-bit/96kHz, 24-bit/192kHz, 24-bit/320kHz or even 32-bit/384kHz. And if we go back to that new definition for high-res audio, you can now add these labels to the mix:

MQ-P: from a PCM master source above CD spec, typically 24-bit/96kHz or 24-bit/192kHz content

MQ-A: from an analogue master source

MQ-C: from a CD master source (44.1kHz/16-bit), then upsampled to higher resolution

and MQ-D: from a DSD/DSF master source – typically 2.8MHz or 5.6MHz content

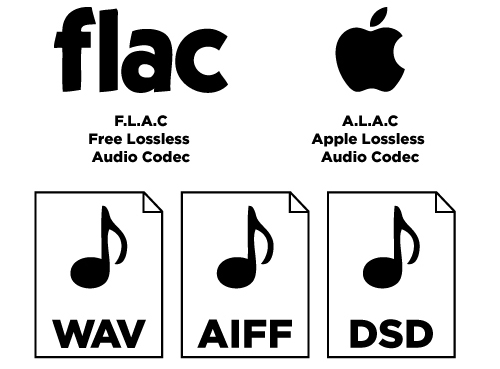

Then there's the issue of different audio formats: I've already mentioned CD, SACD, DVD-A, PCM, Ogg Vorbis and AAC. To that you can add DSD, APE, FLAC, ALAC, WAV, AIFF and MP3, among others. Confused yet? I'm not surprised.

Worse, not all products can handle all types of high-res files. Some will only play up to 24-bit/96kHz, and some only via USB, some via S/PDIF, others via wired ethernet but not wi-fi. Many don't handle DSD (Direct Stream Digital) at all.

If high-resolution music is really going to break through into the mainstream, then we have to make it much simpler to understand – and use. Hi-fi enthusiasts may be prepared to spend time researching where to get the best downloads and figure out which files will, or won't, work on their system, but the average music lover will just want to plug and play.

Did I say plug and play? That's another thing: connectivity formats such as DLNA and UPnP (Universal Plug 'n' Play) are anything but. If you've ever tried to connect a NAS device to your network player, you'll know what I mean.

MORE: Onkyo and 7digital to launch high-res music store in Europe and US

All of which is a shame. Because, as hi-fi lovers, we should care about sound quality. Getting the world to upgrade from low-bitrate MP3s to higher quality music is surely a good thing. But if the consumer electronics industry and record labels continue to make high-res audio confusing and expensive, without a simple, clear message, then frankly most people will stick with what they've got.

As my colleague, magazine editor Simon Lucas says in the August edition of What Hi-Fi? Sound and Vision: "What's not to like about digital music files so much bigger, packed with so much more information than CD equivalents? One listen to well-mastered high-res audio, in my experience, can make an evangelist out of a pragmatist."

I agree, Simon, I agree. But we need to sort out the mess of formats and hardware compatibility before high-res truly has a chance of becoming mainstream.

See the August issue of What Hi-Fi? Sound and Vision, on sale 2nd July, for our test of the latest portable high-res music players from FiiO, iBasso and Sony

Andy is Global Brand Director of What Hi-Fi? and has been a technology journalist for 30 years. During that time he has covered everything from VHS and Betamax, MiniDisc and DCC to CDi, Laserdisc and 3D TV, and any number of other formats that have come and gone. He loves nothing better than a good old format war. Andy edited several hi-fi and home cinema magazines before relaunching whathifi.com in 2008 and helping turn it into the global success it is today. When not listening to music or watching TV, he spends far too much of his time reading about cars he can't afford to buy.