Behind the scenes at Sony's UK 3D Centre

I've spent the day at Sony Professional's UK headquarters, being given a behind-the-scenes look at its new 3D Centre (above).

The purpose-built venue is partially used as a showcase for 3D technology, and also to host training sessions for professional film and TV broadcasters who want to learn more about how 3D works, how best to film it and avoid the pitfalls of creating bad 3D footage.

Sony has similar 3D training centres in Culver City, California (used by Sony Pictures) and Mumbai, India, with further sites planned for Hong Kong and Moscow.

A selection of early 3D still picture viewers

Paul Cameron, Sony Professional's training director, gave us a fascinating insight into the history of 3D and its development.

Did you know, for example, that the first 3D film was made in 1903? Or that Alfred Hitchcock experimented with 3D when filming Dial M For Murder, but the 3D version was never shown to the public.

3D glasses come in many different forms

Get the What Hi-Fi? Newsletter

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

Cameron says there have been three distinct periods during the twentieth century when 3D enjoyed something of a boom at the cinema, followed by a crash.

First came anaglyph glasses, the cheap cardboard ones you may have seen with cyan and magenta lenses, which were popular in the early 1920s. But by 1926 3D fell out of fashion, mainly because the 3D effect was unconvincing and colours were poor.

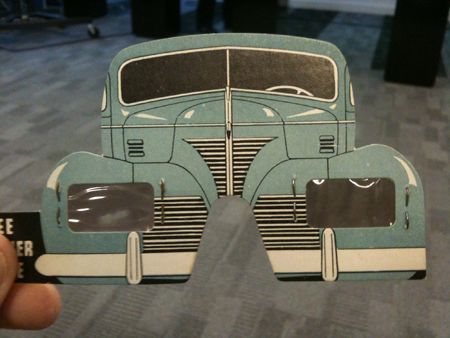

Then in 1939 Chrysler developed the first pair of polarised 3D glasses which were shown at the New York World Fair (above).

A second 3D boom at the cinema followed from 1951-54, this time using polarising projection and full colour, but again it failed and by 1956 fell out of fashion.

The third 3D boom came in the early 1980s, with the advent of dual 70mm projection and better synchronisation, but once again the bubble burst in 1987.

It's interesting to note that the development of 3D seems to go in 30-year cycles: the 1920s, 1950s, 1980s and now 2011.

A very early 3D camera

However, with the development of shuttered 3D technology and digital projection in the 1990s, Cameron believes 3D at home and in the cinema is now here to stay.

But the programme and film makers have to learn from the mistakes of the past, he says.

"3D will not take off if we make the same mistakes as in the 1950s and 1980s. There's no point introducing 3D for an elite audience – it needs to be developed for home viewing."

Among the key challenges for 3D in the home are making sure that images are sufficiently bright, that those watching have a sufficiently wide viewing angle, there are no drawbacks when watching TV in 2D, and that 3D technology is cost effective.

Today's active-shutter 3D glasses

On that last point, Cameron admits that the high price of active-shutter 3D glasses is a point that "needs to be addressed".

Yet, despite the high cost of active 3D glasses, he still believes that active-shutter technology is the best solution for 3D viewing in the home as shuttered screens are Full HD, whereas passive designs are not and the filters fitted to passive TV screens reduce brightness when viewing in 2D. LG, which is backing passive technology, would no doubt disagree.

Sony firmly believes that this time round, 3D content will be sufficiently compelling to convince TV viewers to adopt the technology.

The company was heavily involved in providing the 3D camera rigs and outside broadcast (OB) trucks for last year's World Cup in South Africa, and will do so again for the 2014 World Cup in Brazil.

Sony has installed six 3D cameras at Wimbledon

It also worked closely with Sky last year to film the Ryder Cup in 3D with 24 cameras, recently filmed the beatification of Pope John Paul II in Rome for Vatican TV in 3D, and will shoot this year's Wimbledon finals on Centre Court for the BBC with a six-camera rig (see our news story).

And with an increasing demand for opera and ballet to be shot in 3D, particularly for Sky Arts, it looks as if Sony Professional's 3D division will be busy for some time to come.

Andy is Global Brand Director of What Hi-Fi? and has been a technology journalist for 30 years. During that time he has covered everything from VHS and Betamax, MiniDisc and DCC to CDi, Laserdisc and 3D TV, and any number of other formats that have come and gone. He loves nothing better than a good old format war. Andy edited several hi-fi and home cinema magazines before relaunching whathifi.com in 2008 and helping turn it into the global success it is today. When not listening to music or watching TV, he spends far too much of his time reading about cars he can't afford to buy.