90 years after its first transmission, BBC radio – from Arthur Burrows to Danny Baker

I have to whisper this around the office, but considering I spend my life surrounded by all things audio and visual, I’m not a great watcher. Yes, we have a big TV at home, and occasionally will load up a movie on a Friday or Saturday night, but given the choice of broadcasting, I’d always go for radio – and speech radio at that.

Seems I’m not alone: the BBC started daily broadcast radio services 90 years ago today, and its services are still going strong, despite the ever-growing choice of content available to stream or download. Or even watch.

89% of us listen to at least some radio every week, and well over a billion hours of radio were listened to in the last three months, with 43m hours a week of that total now being online.

Radio Reunited

The very first BBC broadcasts came from Marconi’s 2LO studio in the Strand, London, starting at 5.33pm on November 14, 1922, and to mark the event some 60 BBC stations will be joining forces at the same time this afternoon to broadcast Radio Reunited, a specially commissioned three-minute programme of listeners thoughts, set to music by Damon Albarn (below).

Heard both in the UK and around the world via the BBC World Service, the programme will comprise one listener’s thought from each participating station, mixed together by Albarn, who says ‘I love the idea of stations across Britain and the World Service coming together, with all of our different lives and circumstances, even if it's only for a few minutes. It's a powerful idea,’

All the contributions made by listeners will be preserved by the Mass Observation Archive at the University of Sussex to ensure they’ll still be around in 90 more years, and can be made available for academic research, while a BBC website will also showcase the best of the listeners’ thoughts.

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

The special programme will be broadcast on – deep breath – BBC Radio 1, BBC Radio 1xtra, BBC Radio 2, BBC 6music, BBC Radio 3, BBC Radio 4, BBC Radio 4 Extra, BBC Asian Network, BBC Radio 5live, BBC London 94.9, BBC Radio Berkshire, BBC Radio Kent, BBC Oxford, BBC Sussex, BBC Surrey, BBC Radio Solent, BBC Radio Cambridgeshire, BBC Essex, BBC Three Counties Radio, BBC Radio Norfolk, BBC Radio Suffolk, BBC Newcastle, BBC Tees, BBC Radio Cumbria, BBC Radio Manchester, BBC Radio York, BBC Radio Humberside, BBC Radio Sheffield, BBC Radio Lancashire, BBC Radio Stoke, BBC Radio Leeds, BBC Radio Merseyside, BBC Coventry & Warwickshire, BBC Radio Derby, BBC Hereford & Worcester, BBC Radio Leicester, BBC Lincolnshire, BBC Radio Northampton, BBC Radio Nottingham, BBC Radio Shropshire, BBC WM, BBC Wiltshire, BBC Radio Gloucestershire, BBC Radio Bristol, BBC Radio Cornwall, BBC Radio Devon, BBC Guernsey, BBC Radio Jersey, BBC Somerset, BBC Radio Ulster, BBC Radio Foyle, BBC Radio Nan Gaidheal, BBC Radio Scotland, Radio Wales, BBC Radio Cymru and many BBC World Service outlets, including Arabic, Swahili, Hausa and English Language services

Also starting tomorrow is 90x90 – ninety programmes, each of a minute and a half, and each representing one of the past 90 years, to be broadcast on Radio 4 Extra starting after Radio Reunited airs today, and running for the next 11 days. They’ll also be heard on other BBC radio networks, and all of the programmes are available for online listening here.

Where all this started was with a news bulletin read on the British Broadcasting Company by then Director of Programmes Arthur Burrows (left).

Each bulletin was read twice, once quickly and again slowly, with listeners asked which version they preferred, and the content of the first one contained stories including a speech by Conservative leader Bonar Law, a train robbery, a report on the fog in London that day and ‘the latest billiards scores’.

News was broadcast again at 9pm, again by Burrows, who had previously worked for Marconi’s Wireless Telegraph Company, broadcasting from the 2LO station before the BBC was formed.

He said some time later that ‘I am prepared to assert that there is no more exacting test of physical fitness and nervous condition than the reading of a news bulletin night after night to the British Isles.’, and commented that foreign news was a headache, thanks to ‘place names strange to the eye, and looking as though they had fallen accidentally from a child's alphabet box.

Oh, and there was the also first weather bulletin, although regular forecasts didn’t start until March 1923, and the Greenwich Time Signal – the 'pips' – arrived the following year.

The BBC: a staff of just four

So why was the Director of Programmes reading the news? Simple, really – the total staff of the BBC at the time was just four people! The BBC itself had been formed as a consortium of radio manufacturers, in the wake of the rush for licences to broadcast after Marconi started his 2LO transmissions.

The Postmaster General advised the manufacturers to form the consortium, and in October 1922 the BBC was formed.

Radio sets, such as the crystal set seen left, had to be made in Britain, Post Office approved and carry a BBC stamp, and listeners needed a licence costing 10s (50p) a year, half of the income from this going to the BBC.

That 10s would be the equivalent of £23.30 in modern terms (according to the Bank of England inflation calculator), for which you got just one 'channel'.

The day after the first BBC programmes from London, similar broadcasts were made from 5IT Birmingham and 2ZY Manchester, and on that day the bulletins were able to announce the results of the 1922 General Election, which had just been declared.

However, with only 30,000 or so radio licences across the country, this event saw ‘listening-in parties’, the precursor of the viewing parties Britain would see at the time of the 1953 Coronation.

By the end of the year John Reith (left), who’d played a major part in the establishment of the organisation with his remit ‘to bring the best of everything to the greatest number of homes’, was made general manager.

Reith was in his early thirties when he took the job, and would go on to guide the BBC until 1938, the principles by which he wanted programmes to be made – of fairness and equality, with a commitment to public service – eventually giving the word 'Reithianism' to the language.

Wiithin 12 months, the BBC was broadcasting a mix of plays, music and variety programmes, its studios using these huge and unwieldy 'meat safe' microphones (right), so-called due to the metal enclosure around the microphone element, designed to protect the electronics and resembling the 'cages' in which meat was commonly stored at home in the days before refrigeration.

Standing over 1.5m tall, these microphones required an array of batteries on the floor to power them, and an adjacent roomful of amplification.

But as the broadcast output grew, there were no daytime news bulletins – a deal struck in December 1922 between the BBC, the newspapers and the press agencies agreed that there’d be no news on the radio before 7pm, to avoid damaging newspaper sales.

It wouldn't come back until 1926, covering the General Strike with mixed results: ministers including Churchill were in favour of taking over the BBC to use to broadcast Government policy, while the supporters of the strike thought the company was already doing just that, and nicknamed it the 'British Falsehood Company'.

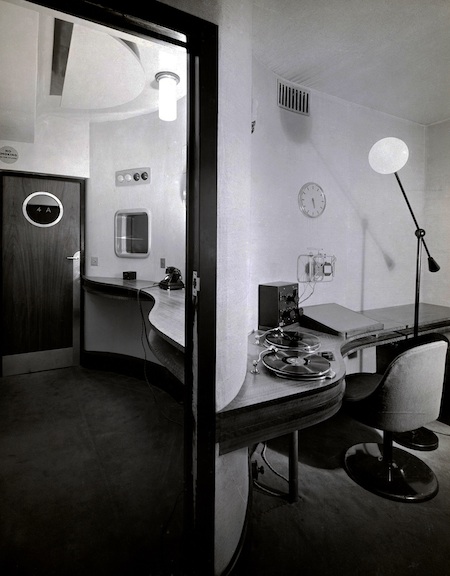

Just a year after the first broadcasts, the BBC had moved to its first real premises, in the Institute of Electrical Engineers building at Savoy Hill. One of the Savoy Hill studios is shown above.

It was described at the time as the most pleasant club in London – despite the daily visit of the ratcatcher and boys employed to spray germicide to keep the announcers infection-free!

The same year the Radio Times was launched, in response to the newspapers’ refusal to carry radio listings in case listenership started to affect their sales.

Whatever the arguments, in 1927 the BBC changed from Company to Corporation, was granted its first Royal Charter and was now headed by the newly knighted Sir John Reith.

By then its first high-power transmitter had been opened at Daventry to boost coverage, and in 1926 2.25m radio licences were held – a much faster uptake than anyone had anticipated. That number would rise to 8.5m by 1938, with 98 per cent of the population able to listen.

Live sports: Twickenham, the National and Association Football

And some familiar radio ideas were taking shape: in 1927 the first live sports coverage was commentary on England v Wales at Twickenham, followed the same year by events including the Grand National, the Boat Race, Wimbledon and Association Football.

The first BBC Prom was broadcast in 1927, the BBC having stepped in when founder Henry Wood’s series ran into financial problems after music publisher Chappell & Co withdrew its sponsorhip. For the next three years concerts were broadcast by 'Sir Henry Wood and his Symphony Orchestra', until the BBC Symphony Orchestra was formed in 1930.

The BBC still sponsors the Proms, as it has since 1927 with only a short break in 1940-41 when it was decided to decentralise its music department. The 1940 Proms season was only four weeks long, while a 1941 bomb gutted the Queen's Hall, until then home to the concerts since the 1890s.

The season was moved to the only other venue able to stage big orchestral concerts: the Royal Albert Hall.

Short-wave services to the Empire began – the beginnings of the World Service – and the BBC Christmas Fund for Children (which became later Children In Need) was launched. So Children in Need is 85 years old this year – wonder if anyone’s noticed?

From there on in, famous programmes began: the daily weekday church service started in 1928, Toytown (with Larry the Lamb and co) began in 1929, and the same year also saw the start of The Week in Westminster, still running on Radio 4. Then it was called The Week in Parliament, and began with a series of talks by women MPs.

The 1930s saw that huge boom in radio listening I mentioned before: in 1932 the BBC moved from Savoy Hill to the world’s first purpose-built broadcast facility, Broadcasting House (seen above during its construction).

Built on the site of the former home of the inventor James Watt, the ‘liner’ just north of Oxford Circus had nine floors, with three more below ground, and originally all the studios were in the heasy central tower, on steel structures designed to give some acoustic isolation.

BH made its first broadcast on March 12, and was officially opened on May 1. Church services started to be broadcast from the adjacent All Souls, Langham Place (above), in June, and that December George V made the first Empire Service Christmas Day broadcast.

The BBC was clearly very proud of its new home, described by the Architectural Review of 1932 as the ‘new Tower of London’: its 1933 yearbook reported that it had 800 doors – one for each member of staff then working there! – more than one radiator per person, one clock for every eight staff and 8.125 light bulbs per person.

Which is handy if it’s cold, dark and you want to know the time.

Broadcasting House: lots of doors, lights and clocks!

However, even before the recent remodeling to add the massive new extension to the building, there was something odd about BH: it was asymmetrical, the original plans being modified when Langham Street residents complained they’d literally be living in the shadow of the new building.

Another famous alteration was required, this one being an adjustment of the scale of the nether regions of the naked statue of Prospero from Shakespeare’s The Tempest, sculpted by Eric Gill and in pride of place on the 'prow of the ship'.

A question was asked in the House of Commons whether the lavish nature of Prospero’s endowment didn’t offend public morals, and it’s believed Lord Reith asked Gill to scale things down a bit.

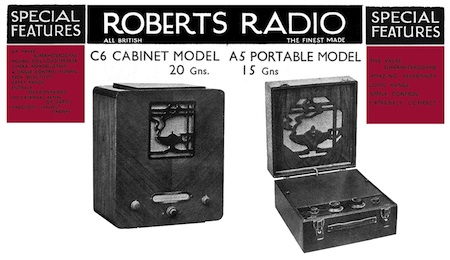

Also founded in 1932 was a company whose rise would parallel that of the BBC – Roberts Radio, which is celebrating its 80th anniversary this year, and sent us this little ‘radio cake’ (above) to mark the event. We haven’t had the heart to eat it yet!

Started in 1933 by Harry Roberts (left) and Leslie Bidmead, the company wanted to make not just radios, but sets designed to last a lifetime and be passed down from generation to generation.

At first the company made just three radio sets a week, but after Harry Roberts visited Harrods to demonstrate his new model, sales began to fly. Other department stores also made orders, and the company was off and running, then as now specializing in portable radios.

In fact, Roberts has made very few table radios in its time, the one in the advert below being a rare exception.

It now holds two Royal Warrants, and as well as being famous in the UK, sells its traditionally styled radio sets worldwide, having built its business on exports alongside its domestic sales.

It also has the added distinction of employing someone who must be one of the longest-serving members of staff in any company in the UK. Stan Vandenbergh joined the company in 1942 aged 14 – Roberts had spotted Stan outside the factory gates waiting for his brother to finish work, and as soon as he was old enough, offered the boy a job.

70 years on, he’s semi-retired but still works a three-day week at Roberts – having moved from assembly to sales in the early 1970s, he’s now responsible for ensuring sufficient stocks of Roberts products are available through independent retailers.

In 1933, the BBC radio service got its first female announcer, Sheila Barrett, and the Droitwich long-wave transmitter replaced the Daventry installation.

Letters from London and America

Meanwhile in 1935, after a number of firsts involving transmissions of programmes to and from America back in the early days of the BBC, Alistair Cooke (above) began to broadcast his weekly programme The American Half Hour.

Cooke (left), who was born in Salford – a place much later to play a huge part in the BBC’s radio service as part of the latest round of decentralisation – and had studied in the States, was originally the BBC’s film critic, despite arriving 24 hours late for his job interview. Well, he did have to get on a liner from New York to get there!

He also worked as US broadcaster NBC’s man in London, broadcasting a weekly 15 minute talk called London Letter to American listeners. When he decided to emigrate for good to the States he suggested to the BBC he might do the same thing in reverse, the idea was accepted, and after a few fits and starts – and a lengthy delay during World War II, American Letter began airing on the BBC each week in 1946.

58 years, 2869 letters and a change of name later, Letter from America finally came to an end in 2004, having become one of the mainstays of the BBC Home Service, later Radio 4, and a Sunday morning listening institution for millions. Cooke, by now 95, died four weeks later.

You can listen to an archive of over 900 of Cooke’s letters, including the first and last ones, here .

In 1939, with war looming, the BBC shut down its fledgling TV service, about which I wrote a week or two back, on September 1st.

Two days later, the BBC carried broadcasts by Neville Chamberlain and King George VI, bringing listeners news that the long-anticipated war was finally declared.

Less than a month later, Churchill made the first of his famous wartime radio broadcasts.

With TV gone – even before the war, performers on ‘the wireless’ were paid more than those on television, reflecting the relative sizes of the audience –, radio carried on, the existing BBC national and regional programmes being replaced by the new Home Service.

The new sound of the BBC wasn’t a hit with listeners – we radio fans always complain when a well-known format is messed around with, and this time people said there were ‘too many organ recitals and public announcements’!

Music While You Work

The BBC would go on to keep wartime listeners informed and entertained with programmes such as Worker’s Playtime and Music While You Work, setting the pattern for the shop-floor or office background music of today; reporting from the likes of Richard Dimbleby, Frank Gillard, Godfrey Talbot and Wynford Vaughan-Thomas; the debut of ‘forces sweetheart’ Vera Lynn – about whom the BBC governors said ‘Popularity noted, but deplored’ –; and the launch of one of the BBC’s real long-runners, Desert Island Discs.

Starting in January 1942 with the music selection of comedian Vic Oliver, who chose the likes of Jack Hylton and his orchestra performing Happy Days Are Here again, and Wagner’s Ride of the Valkyries, it’s been on the air for 70 years, and has clocked up 2915 episodes, many of which are available on a dedicated BBC archive.

But all that was to come, along with the launch of the BBC’s Light Programme, developed from the wartime Forces programme, which would go on to become Radios 1 and 2 in the 1960s, and the Third programme, launched alongside the Light in 1946, and later to become Radio 3.

Now, we live in a multiplatform radio world, with programmes available via analogue or digital receivers – at least for the moment! – via our cable or satellite service, or as part of the digital Freeview package, or streamed over the internet.

We can catch up with programmes broadcast days or weeks before via the BBC iPlayer on our Smart TV, Blu-ray player, computer, phone or tablet, and download podcasts to listen later to programmes we may have missed.

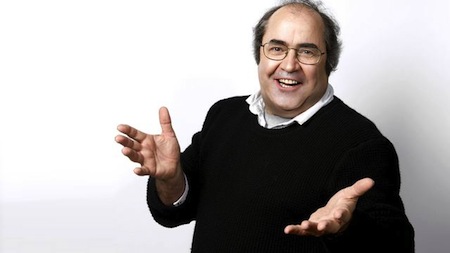

To slightly misquote a modern radio great, Danny Baker (above), all of this may be way beyond ‘what Marconi had in mind when he legged it down to the patent office’, but one thing's for sure – radio has never been more available.

And what of Baker’s broadcasting ideal, mentioned in his acceptance speech last night in Salford when he was inducted into the Radio Hall of Fame, of ‘the dialogue that simply exists between the person behind the mic and the audience’?

Well, though he may feel some current BBC management has attempted to meddle in that direct communication with its plans to reduce his daily London show to a single weekly slot, Baker's view is surely as vivid a statement of how radio should be in the 2010s as Reith's was for the early days of the medium.

Truly great radio, be it speech, drama, news, documentary or music, has an intimacy of communication with the listener that even the very best of TV would struggle – and eventually fail miserably – to match.

And that all started with the very first BBC broadcast, exactly 90 years ago today.

Written by Andrew Everard

Andrew has written about audio and video products for the past 20+ years, and been a consumer journalist for more than 30 years, starting his career on camera magazines. Andrew has contributed to titles including What Hi-Fi?, Gramophone, Jazzwise and Hi-Fi Critic, Hi-Fi News & Record Review and Hi-Fi Choice. I’ve also written for a number of non-specialist and overseas magazines.