What Hi-Fi? Verdict

This is world-class control: Halcro’s Equinox preamplifier proved to be perfectly presented and balanced from the deepest bass to the highest treble, zero background noise at any time, not to mention an absolute lack of audible distortion.

Pros

- +

Unmatched sound quality

- +

Phase inversion outputs

- +

Incredibly high performance

Cons

- -

No headphone output or phono input

Why you can trust What Hi-Fi?

This review and test originally appeared in Australian Hi-Fi magazine, one of What Hi-Fi?’s sister titles from Down Under. Click here for more information about Australian Hi-Fi, including links to buy individual digital editions and details on how best to subscribe.

Halcro should need no introduction to those “skilled in the art” of audio because it is one of the most famous names in hi-fi history. Indeed, for a time, it was the most famous name.

For the uninitiated, or readers for whom Halcro is just a mere memory, the company was named after its founder, Dr Bruce Halcro Candy, who started building amplifiers as a teenager, aiming to combine his technical skills and love of music to build the world’s ‘ultimate’ amplifier. In 2001 he told Stereophile magazine’s Jon Iverson that his lifelong passion for music and his ability to evaluate audio components were informed by his rare ability to hear frequencies so high (far above 20kHz) that they are inaudible to most other people.

Candy mothballed Halcro in 2011 after being headhunted by South Australian company Minelab, where his expertise subsequently resulted in him winning the Clunies Ross Award from the Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering (ATSE). Minelab proudly describes him as – deep breath – “one of the world’s leading experts for the development of high performance hand-held metal detectors whose work will benefit the industry for decades to come, including de-miners who are lessening the landmine menace worldwide, gold prospectors who have generated wealth both here in Australia and worldwide and the archaeological community who benefit from the many finds by detectorists using his technologies.”*

Halcro re-emerged as an active amplifier manufacturer in 2015 courtesy of a collaboration between Lance Hewitt, formerly Candy’s lead engineer; Mike Kirkham of Magenta Audio, an Australian audio importer, retailer and distributor; and Dr Peter Foster, who holds a PhD in Physics from the University of Adelaide and was formerly a Senior Laser Physicist at Norseld Pty. Ltd and a Guest Scientist at the Department of Metallic Materials, University of Bayreuth, Germany. The trio purchased Halcro’s assets from Candy’s company (BHC Consulting), including its brand name, portfolio of audio patents, tooling and a batch of mothballed stock.

(*Not to mention 'The Curse of Oak Island', where the treasure-hunting team favours Candy's Minelab gear for all their metal detecting requirements.)

Despite Candy no longer being involved, Kirkham says that the DNA inside the Equinox preamplifier on test here is derived directly from Candy’s patented designs. For example, it uses the same relay-switched, low-noise resistor network in the gain stage that was used in Halcro’s classic dm10 preamplifier, while the active gain stages are based on a completely new amplifier topology developed for the input stage of Halcro’s Eclipse power amplifier, the stereo version of which (there is also a mono model) I reviewed a few Australian Hi-Fi issues ago.

“All active components are configured in such a way as to ensure that they are always operating at the optimum point in the I-V curve, resulting in negligible distortion, high slew rate, fast transient response and extreme linearity,” says Lance Hewitt. “This is one of the signature, proprietary approaches that separates Halcro from all other amplifier designs.”

Another of Halcro’s ‘signature’ design approaches is the separation of the power supply circuitry from the audio circuitry through the use of separate enclosures. This was a feature of the original dm58 power amp of the early noughties that carried over to the current generation of Eclipse models and, now, the Equinox. As with that dm58, the power supply here is a switch-mode design, with the circuit switching at well over 100kHz to remove it far above the audio band. “We use custom transformers and substantial filtering to ensure very clean, high-current delivery to the amplifier chassis,” explains Hewitt.

When I asked Kirkham about the impetus behind developing the Equinox, he said: “The goal was to create an amplifier that would be transparent, able to peer into the music and resolve the finest detail while presenting everything in a very natural way. Months were spent in component selection, and carefully voicing components in a painstaking series of double-blind listening tests.” Answering my question about why the preamp didn’t take its external design cues from the original dm8 and dm10 preamps, or even the Eclipse power amps, Kirkham said: “The Equinox represents a bridge between the iconic, signature Halcro designs to date and the design language of the future.”

Equinox preamp: build & facilities

Strangely enough, while everyone at Halcro is completely onboard with the rationale behind the ‘two-box’ design of the Equinox, I detected a little frisson about a preferred name for each box, though the official consensus is that one is called ‘Control’ and the other ‘Audio’.

I placed the ‘Audio’ box on my equipment rack, and initially its chassis rocked quite alarmingly. “Don’t tell me the courier has dropped it and warped the chassis!” I thought to myself. However, upon upending the chassis I discovered that the four high-gloss chromed, conically shaped feet are adjustable, and for some reason one of them was almost fully extended. It was, therefore, a simple matter of winding it back to its proper place to ensure stability. These feet do more than just enable levelling, though. According to Kirkham they also “minimise structural resonances and reduce interference with delicate audio signals”.

Upending the chassis revealed a small, white, plastic multi-way connector I wouldn’t have otherwise noticed, and which doesn’t appear to be mentioned in the company’s literature, although I didn’t have much to go on since my review unit arrived without a manual. It transpired that it allows the internal software to be upgraded, potentially to change how the Equinox operates. When I asked for an example of what this could mean, Kirkham said that the preamp’s volume control currently enables levels to be adjusted in 0.5dB increments, meaning there are 160 possible settings that would require many rotations to go through them all. If they get feedback from owners that this is several turns too many and they would prefer 1.0dB increments, this could then be changed. Also on the Audio box’s undersection is a small plate that reads “Made in Australia,” so the company is not outsourcing production to China or South East Asia, as many other high-end manufacturers now do.

The Equinox’s two boxes are linked by a short umbilical cord that enables either side-by-side (which I preferred) or stack positioning. If you prefer the latter, it’s best the Control is topmost as, although the 240V power cable connects to it, the signal cables connect to the Audio, so you will have fewer cables hanging in midair. To protect the superbly finished top surface of the Audio chassis, as well as your equipment rack, during this process, Halcro supplies eight protective isolating pucks rather than the usual four.

As for my preference for a side-by-side arrangement, it has nothing to do with sound quality but with how it looks. Quite simply, I didn’t like the boxes’ ‘V’-shaped displays being vertically aligned. Halcro says both units are so well-shielded that it really doesn’t matter how you arrange them: performance will remain the same.

When the Control unit powers on, the LED at the centre of its press-button power switch glows red. When pressed, it flashes red eight times, after which the LED extinguishes and the main ‘V-shaped’, black-and-white, high-resolution LCD touchscreen briefly flashes up the words ‘Equinox Preamplifier,’ together with the software version loaded (Rev 1.3.0 on my sample). It then shows (from the top downwards) the output level, channel balance, active input, phase, and a three-arrow logo that, if pressed, allows you to select your desired active output — and wow, do you have a wide selection to choose from!

But before revealing the numerous outputs available, I should make a small note about the display: some of the Equinox images on the internet show it as being light and dark blue, but the cameras (or phones, as is more likely the case) taken them have been ‘tricked’ into adding such blue-ish tinges; the display is indeed black and white.

There are four balanced outputs (gold-plated XLR) and four unbalanced outputs (gold-plated RCA) that can be configured to be driven ‘in phase’ or with ‘inverted phase’. This allows the Equinox to directly drive two sets of power amplifiers in bridged mode from each of the balanced and unbalanced outputs. Given that the Equinox will most likely be paired with a Halcro power amplifier – the Eclipse Stereo (rated at 180 watts per channel into eight ohms, and 350 watts into four ohms) or a pair of Eclipse Monos (300W into eight ohms and 550W into four) – which would surely provide more than enough power for anyone, I questioned Kirkham about the likelihood of any Halcro customers doing this.

“You’d be amazed by how many people are already using Halcros in bridged mode,” he said. “Just get on the forums and see for yourself; they’re raving about the benefits of the increased power output and the various other sonic attributes of bridged mode operation.”

In addition to the conventional XLR outputs is an additional pair of current-loop ones for each channel – a very rare option in audio – that can also be phase-inverted to facilitate the bridged operation of a pair of amps. “Current-loop interconnects are highly immune to environmental RF noise and may offer significant improvements in noisy environments,” says Hewitt.

Halcro has also supplied a plethora of inputs – seven in total, in fact. Three are unbalanced (gold-plated RCA) and four are balanced (gold-plated XLR). You can choose to have these displayed on the front panel as Input 1, Input 2 etc, or you can allocate each one a name from a pre-programmed selection – CD, DAC, DAT, HT B/P, Phono, SACD, Stream and Tuner. This is all very neat, though I should clarify that, despite the naming option, the Equinox does not have a phono input. If you wish to connect a turntable, you’ll need an external phono stage.

Balance between the two stereo channels is completely adjustable, which is useful for compensating for a channel imbalance in one of your source components (phono cartridges almost always have a higher output voltage in one channel than the other), or if one of your speakers is closer to your listening position than the other or is getting additional help from reflections from a nearby wall or piece of furniture.

Whatever volume and balance setting you set for each input is stored in memory for recall whenever you switch from one to another, so if your various sources have different output voltages, as is almost always the case, this ensures the volume coming out of your loudspeakers will be consistent no matter which source is in use.

For reasons best known to Halcro, it has used various methods for remote triggering at different times in the past, so the Equinox features two remote trigger modes – ‘Level’ (suitable for the Eclipse, dm38 and dm88) and ‘Pulse’ (for the dm58, dm68 and dm78). Between the two you can use the Equinox to trigger components from any manufacturer.

The Equinox is currently available only in Halcro’s matte grey powder-coated finish, which is reflected in the price quoted at the top of this review, but it will soon also be purchasable in the company’s ‘Signature’ hand-painted finish in your choice of colour. Whichever external coating you opt for will be applied to a chassis machined from solid, 16mm-thick aluminium and internally braced to eliminate resonances.

Listening sessions

Volume can be adjusted from -60dB to +20dB in 0.5dB steps. Doing this using the Control unit’s rotary dial takes eight full rotations to get from the lowest setting to the highest, during which a relay inside the unit clicks very loudly. This adjustment method almost gave me a repetitive strain injury!

Luckily, there’s a much quicker alternative: the rotary knob on the remote control. Indeed, you read that correctly: Halcro’s remote features a full-sized volume dial. It works fabulously well, although visually it is bound to divide owners.

Although the remote certainly allows for faster adjustment, that the on-unit dial requires so many turns to go from minimum to maximum isn’t actually really an issue. After all, once you have set your preferred listening level, you’ll only need to rotate the control a little to the left or the right to make minor adjustments, and of course your preferred volume (and balance) settings are automatically stored for each input, so most of the time you won’t need to make adjustments at all. Plus, Halcro may elect to change this via a future software update. Conveniently, you can easily mute the Equinox by pressing the ‘Control’ button on either the front panel or the remote.

For my first listen, how could I not play Billie Eilish’s ‘Hit Me Hard and Soft’ (despite the title’s political incorrectness in these turbulent times, though she did release it before the most recent revelations)? The deeply personal opener (Skinny) was delivered with all of its studio lushness by the Equinox, hardly preparing you for what is possibly the album highlight, Lunch, which follows. The synth-pop is positively palpable via the Halcro and I could hear the perfect focus of sounds centre-stage as well as the completeness of the left-right channel separation of those sounds only in one or the other. I could also hear the phasing effects on Chihiro more clearly via the Equinox than any other preamp in recent memory. This experience made me wish the Equinox had been fitted with a headphone amplifier and output – but maybe that’s just me. The consistent precision of PRAT (pace, rhythm and timing) on Birds of a Feather is exceptional, and just listen to the depth of the bass on Bittersuite after that opening blast of vintage synthesiser sound. The Equinox also revealed the whispered numbers in the close-out to The Diner more clearly than I’ve previously heard... but I’m still not game to call them!

When it comes to break-up albums, they really don’t come any better than Ariana Grande’s ‘Eternal Sunshine’ (Adele’s ‘30’ aside, that is). Her lyrics are spot-on across every track while her vocals are also superb throughout. I just can’t understand how music journalist Michael Cragg reckons Grande has “a voice that could strip wallpaper,” unless I have missed the point he’s trying to make or he isn’t listening via a Halcro set-up (the latter very likely!) The title track (yes, she was reportedly inspired by Michel Gondry’s fantastic film ‘Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind,’ which explores what might happen if people could choose to have unwanted memories erased) is a delightful exploration of syncopation in all its forms, and the Equinox delivers all this delightfulness. The go-to is, however, Grande’s vocals, just because of how superbly well the Halcro communicates them.

If it’s a beautiful voice you’re after, you must hear Melbournian songstress Grace Cummings. Her latest album, ‘Ramona’, is her most sonically ambitious yet and the first in which her vocals are front and centre rather than hidden somewhere backstage. She’s not shy about borrowing from greatness, the title track being a dead giveaway, so you’ll also hear from Neil Young and a Beatle or two, but the album is so wonderfully assembled that everyone quoted would no doubt approve. Check out the stunning sound of the bass and piano on Love and the Canyon!

As my listening sessions progressed, it was evident that the Equinox’s delivery was beautiful no matter what music I fed it. The sound was perfectly presented and balanced from the deepest bass to the highest treble, and there was zero background noise at any time, not to mention a complete and absolute lack of audible distortion. I was convinced I was always hearing exactly what the creative artists and their technicians wanted me to – nothing more, nothing less. I could not wish for more from a preamplifier.

Verdict

Ultimately, Halcro’s new Equinox is the best preamplifier I have ever had the pleasure of auditioning. My pleasure was somewhat tinged by sadness that its asking price is a bit – actually, far – beyond my means. The good news for those who do have the means to purchase a preamp in this upper echelon of high-end hi-fi is that they won’t have to concern themselves about whether they could do any better. They can’t. For anybody who demands the very best, the Halcro Equinox is it.

LABORATORY TEST REPORT

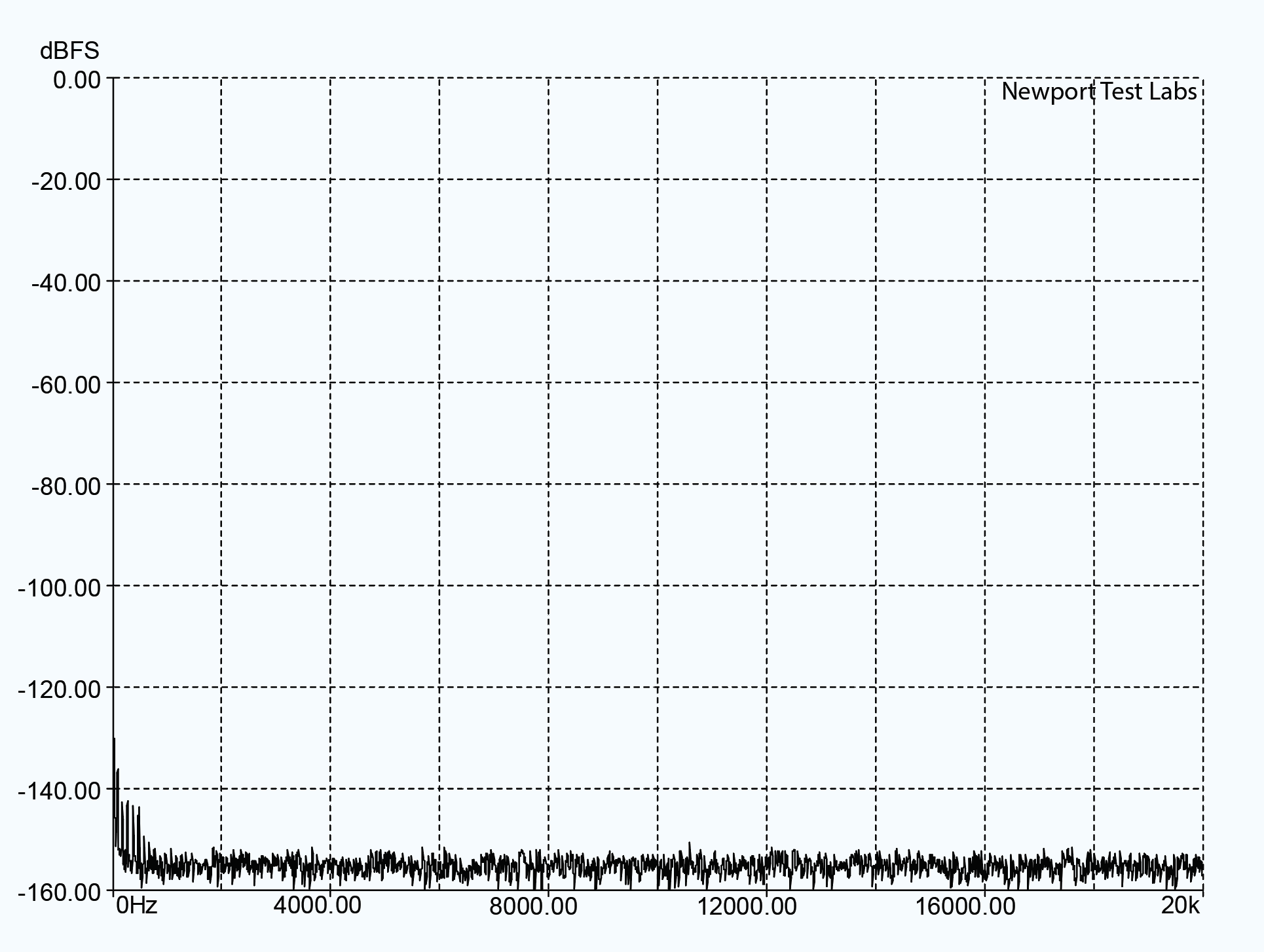

Those interested in a full technical appraisal of the performance of the Halcro Equinox preamplifier should continue on and read this LABORATORY TEST REPORT from Newport Test Laboratories. Readers should note that the results mentioned in the report, tabulated in performance charts and/or displayed using graphs and/or photographs should be construed as applying only to the specific sample tested.

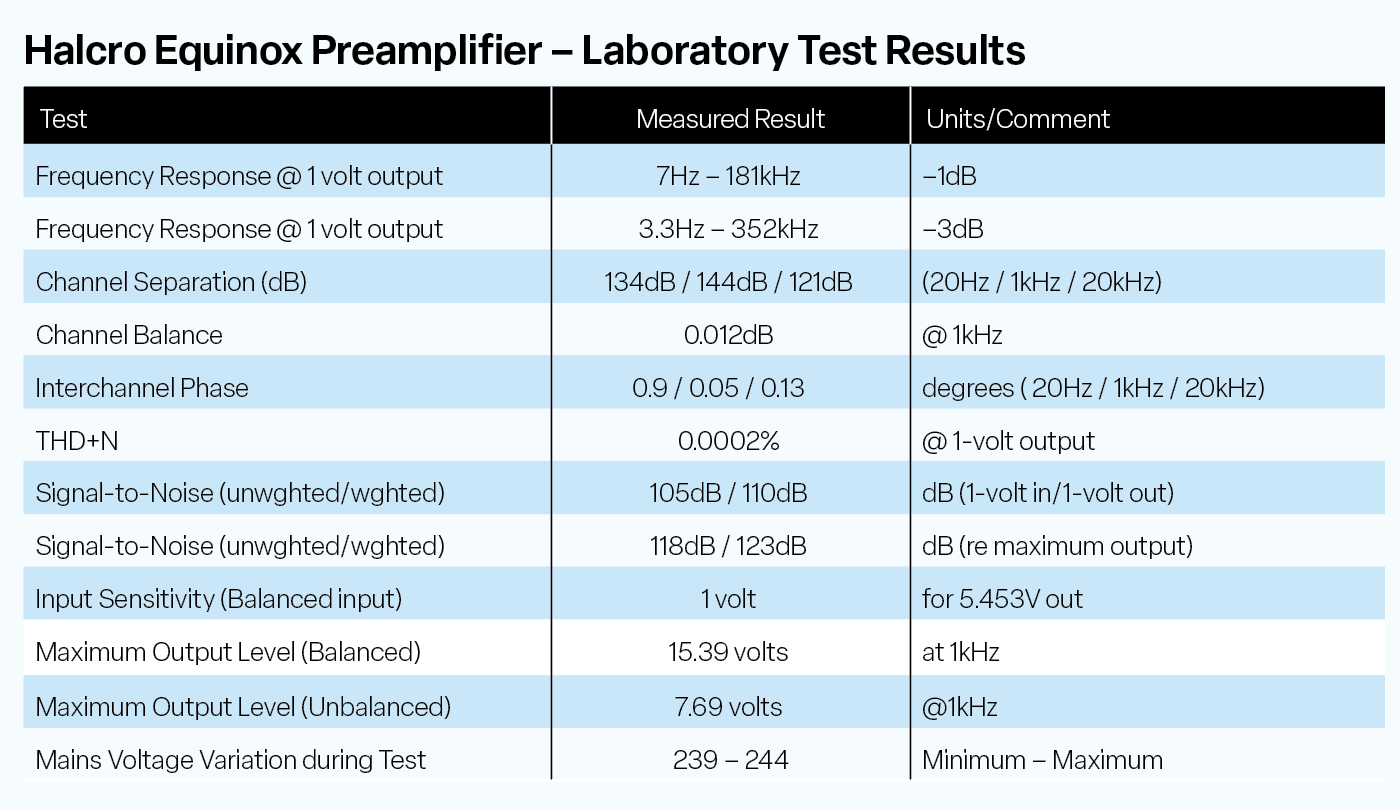

Newport Test Labs measured the Halcro Equinox’s frequency response as extending from 3.3Hz to 352kHz –3dB, showing it is an exceptionally wideband device. The tabulated results above show that the 1dB down-points of the response were at 7Hz and 181kHz. Graph 1 (below), which shows the response between 5Hz and 40kHz (the graphing limits for this particular test), reveals an absolutely ruler-flat line between 80Hz and 15kHz, with the response only 0.01dB down at 40kHz and 0.1dB down at 20Hz. This graph shows the measured audio band response as 20Hz to 20kHz ±0.05dB. It really doesn’t get better than this, nor does it need to!

Separation between the stereo channels was incredibly good, again evident in the tabulated results: 134dB at 20Hz, 144dB at 1kHz and 121dB at 20kHz. Balance between the two channels was also exceptionally good — just 0.012dB at 1kHz.

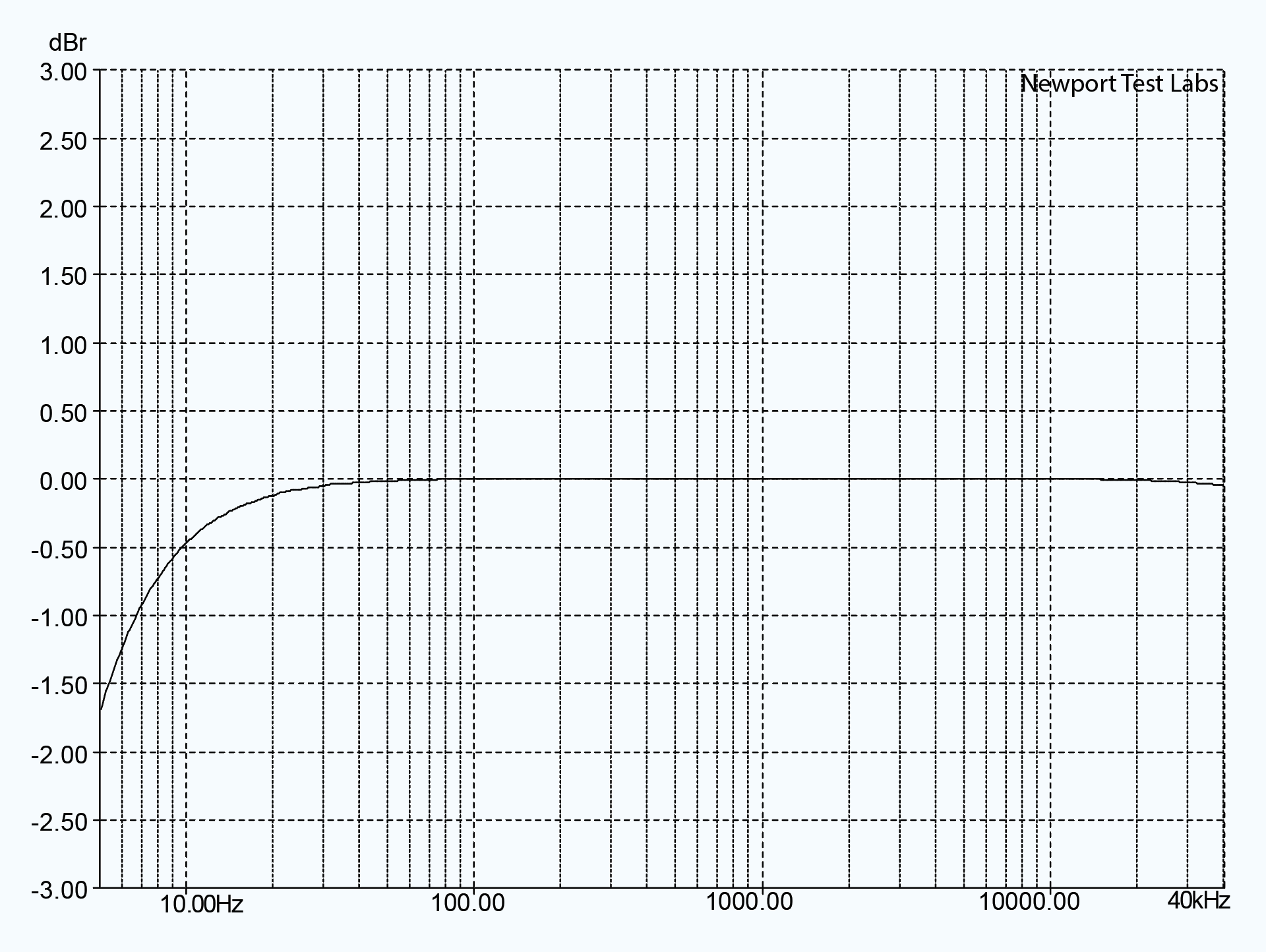

Newport Test Labs measured wideband THD+N as 0.0002%, but this figure is actually the limit of the analyser’s ability to measure distortion, and is mostly the ‘noise’ (+N) component. The distortion component of this result is shown in Graph 2 and you can see that there are essentially zero distortion components higher than –120dB (0.0001%). Look carefully and you will see two ‘blips’ – one at 3kHz and the other at 5kHz – but these are simply residual distortion components of the signal generator used to conduct the test. Essentially, the Equinox’s harmonic distortion was so low it was beyond the measuring ability of Newport Test Labs.

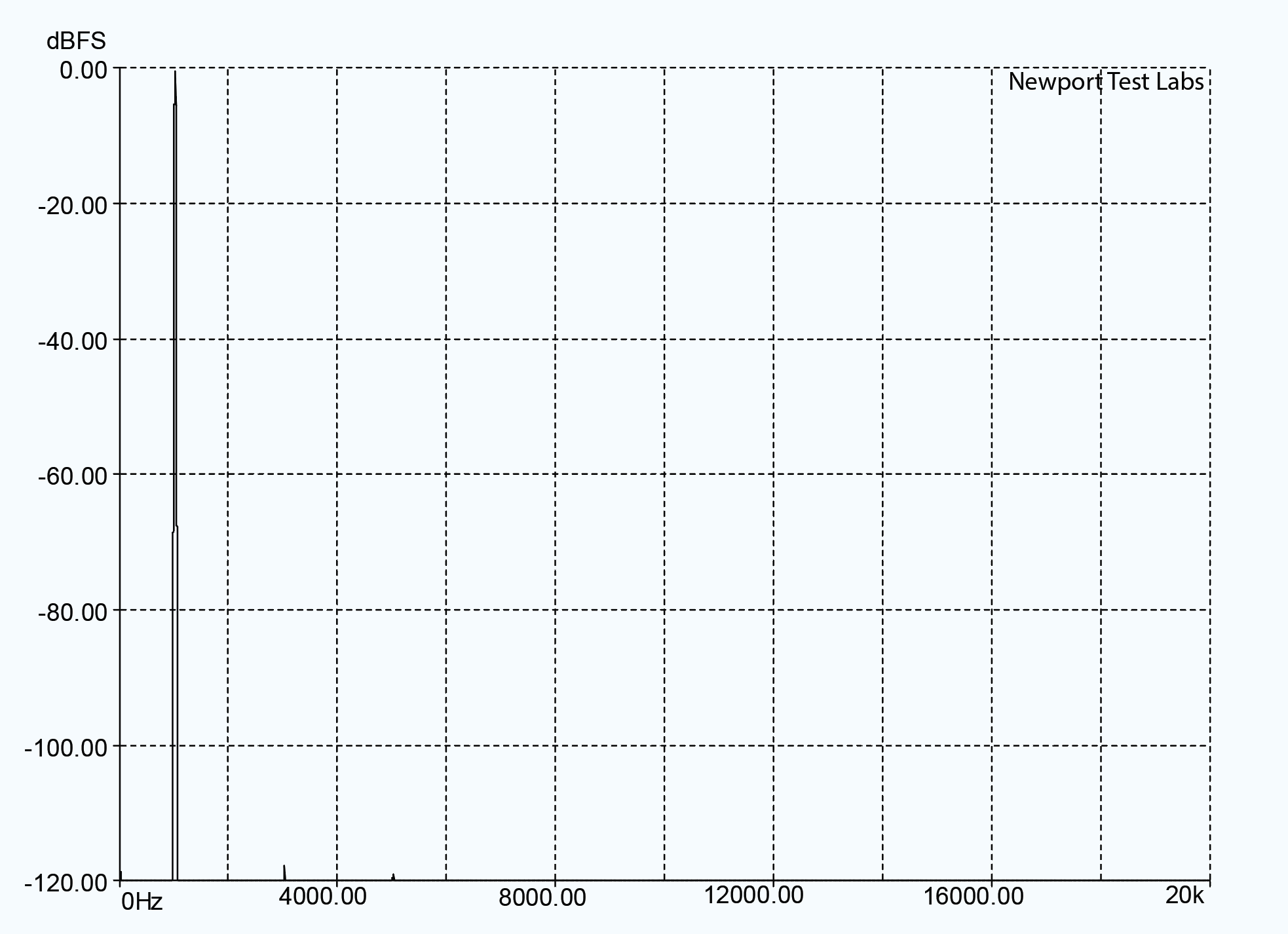

The signal-to-noise measurements were also exceptionally good, with the lab measuring 110dB A-weighted for 1V-in/1V-out and 123dB A-weighted referenced to maximum output which, at 15.39 volts, is a higher output than you’ll ever need. The reason for these exceptionally good SNR results is evident when you look at Graph 3.

It shows the noise spectrum of the Equinox’s output referenced to an output of one volt, and you can see that, other than a tiny signal at 50Hz (some mains frequency bleed-through) at –130dB (0.00003%) and some harmonics of the mains frequency at lower levels, the wideband noise floor is more than 150dB down.

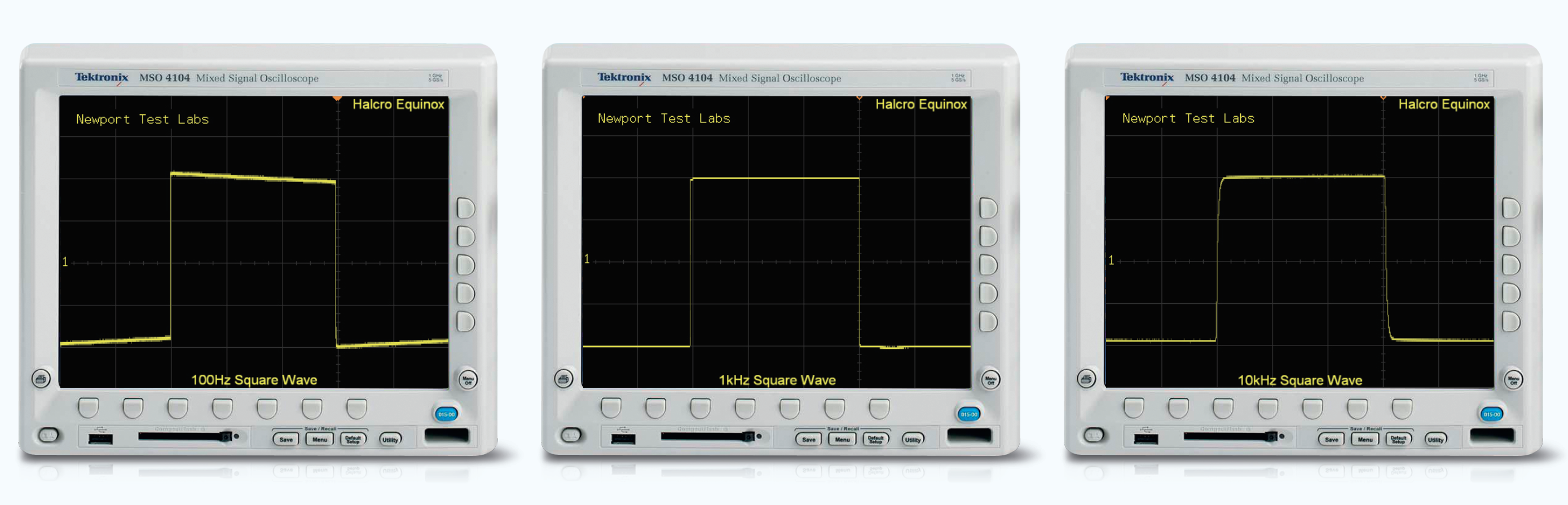

Performance with square waves was also outstandingly good. The shape of the waveform with a 1kHz test signal (centre trace above) is nigh-on perfect, looking as if it came straight from the signal generator. The 100Hz waveform (left) shows the tiniest amount of tilt (the result of the low-frequency response rolling off at 3.3Hz), while the 10kHz waveform (right) shows an exceptionally fast rise-time with only the tiniest amount of leading-edge rounding to reveal the 352kHz upper –3dB down-point of the high-frequency response. The slew rate is therefore very high, as Halcro claims.

The Halcro Equinox is by far and away the highest-performing preamplifier ever measured by Newport Test Labs, returning results close to the limit of (and for distortion, beyond it!) the lab’s ability to measure. Steve Holding