Tidal is definitely lossless, and my mate can prove it

A deep dive into Tidal's claims... and, while I'm at it, Spotify's too

I've written plenty (everyone here at What Hi-Fi? has written plenty) about music streaming services and their quality. We know their bit rates, or at least our DACs may show their bit rates, but there's always the suspicion that streaming music gets somehow compromised during the journey from there to here. Is it truly lossless? Does it arrive bit-for-bit just as it left, or are some chunks thrown away to save bandwidth?

We have just published a piece in Sound+Image magazine (a far-flung Australian outpost of the global but British-based What Hi-Fi? empire) in which one of our longest-standing writers, my friend and colleague Stephen Dawson, has managed to prove one way or the other, for Tidal at least, whether things come through losslessly or not.

I find this rather exciting, so I've asked him if we might share the article more widely here. It's slightly different in its deep diving to much What Hi-Fi? audio commentary, but well worth the read, to reach the truth! Over to Stephen... Jez Ford

My search for losslessness

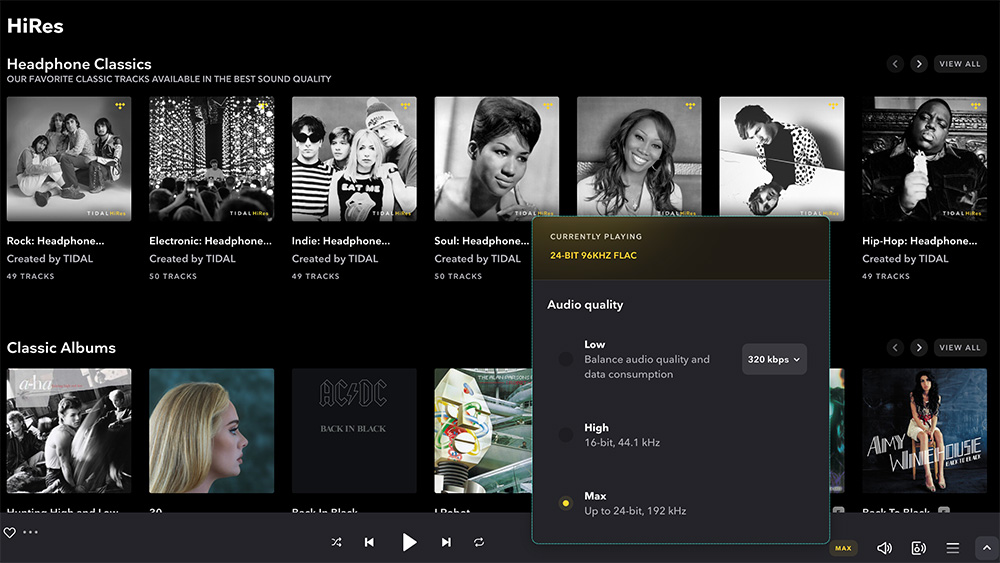

We all know that of the two music streaming services most widely supported by hi-fi hardware, Tidal is technically “better” because its streams are mostly losslessly compressed. The other, more popular one, which is of course Spotify, has promised lossless compression via a Spotify HiFi tier for years but so far failed to deliver; the best you can currently get from the green streaming giant is lossy compression at 320kbps. To give you an idea of how that compares to ‘CD quality’ audio, uncompressed ‘CD quality’ is 1,411kbps while losslessly compressed ‘CD quality’ tends to be in the region of 700 to 900kbps on average.

Now, here’s the thing: we know Tidal is lossless because it tells us so. And while I have no particular reason to dispute the company’s honesty, we in the audio-reviewing world are generally of the view that we should, within reason, test the claims of equipment manufacturers. So why not also test the claims of music platform providers?

Oh, it is easy enough to find equipment that shows you the bitrate of the audio being streamed from services, but that is an extremely crude yardstick. Whatever you might think of digital versus analogue sound, one thing that can’t be disputed with any credibility is that digital files should be infinitely reproducible with zero errors.

So is Tidal truly lossless?

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

This is what I set out to test, and along the way, I decided to see what the real measurable differences were between the (hopefully) lossless service and the self-confessed lossy Spotify.

Procedure

Imagine you are comparing the performance of two audio systems. Rather than the subjective impressions you might gather from listening, you might record the outputs of the two and compare them in a more technical manner. That’s what Bob Carver did back in the 1980s. His (relatively) lowish-cost, high-output power amplifiers were considered inadequate by hi-fi reviewers, so he wired one up to a truly high-end and highly respected amplifier in such a way that supposedly only the difference between the two outputs could be heard from a loudspeaker. He then tuned his amplifier to eliminate any audible difference between the two and released a new model incorporating those changes.

Oh, you can quibble; perhaps it might still have sounded different, depending on the particular load of the loudspeaker (which is always complex and unique) – but, for the moment at least, that hushed the critics.

Those quibbles don’t apply to the exercise I am conducting here. Here I am comparing the raw digital files by doing the digital equivalent of what Carver did back then. I take the actual PCM data from a song on a CD and subtract from it the actual PCM data from the same song on Tidal, and see what is left. If the two are identical, nothing is left and the entire resulting audio will consist of an unbroken series of digital zeros. In this case, the two digital sources – CD and Tidal – are identical. What your CD transport, music streamer and DAC do with them may be different, but the actual source data isn’t.

I then repeat the process with the same songs but this time by capturing the decoded output from Spotify and subtracting it from the CD audio.

Equipment

My usual network streamer is rather expensive with a very high-quality built-in DAC and analogue outputs (both balanced and unbalanced) – but no digital output. So for this test, I used a WiiM Pro streamer, which is modestly priced and works very effectively. Some have criticised the quality of its analogue output – the model-up WiiM Pro Plus upgrades this – but the WiiM Pro also provides digital audio outputs via coaxial and optical. I fed the optical output to an RME ADI-2 Pro FS R Black Edition ADC/DAC, which was connected to a notebook computer via USB. While the RME device can support sampling rates up to 768kHz, I had to switch it to multichannel mode to access the digital inputs, which limited support to 192kHz. Still, as Tidal’s highest of high-resolution audio streams are limited to 192kHz, that was fine.

I used two cables: a mid-priced Toslink cable I bought probably twenty years ago at a local electronics store, and a mid-priced USB cable of similar vintage. As we will see, they did not appear to degrade the transfer.

In my initial experiments, I used Cool Edit 2000 as my recording software. This gave promising results, but it soon became clear that the Windows audio system was adding one bit of dither (that’s a random addition of 0 or 1 bit to each sample). So for these tests, I used Reaper, a low-cost but highly competent multichannel digital audio workstation, saving the recordings in WAV format.

I then used Cool Edit 2000 for the comparisons. Don’t laugh; I paid the shareware (remember that?) fee for Cool Edit sometime in the late 90s, but it still works perfectly – better, actually – these days on Windows 11 machines, a quarter century later, with no updates! (Adobe bought it, and it became the basis of Adobe Audition.) It is incredibly powerful and allows analysis and editing even to the single sample level.

Music choices

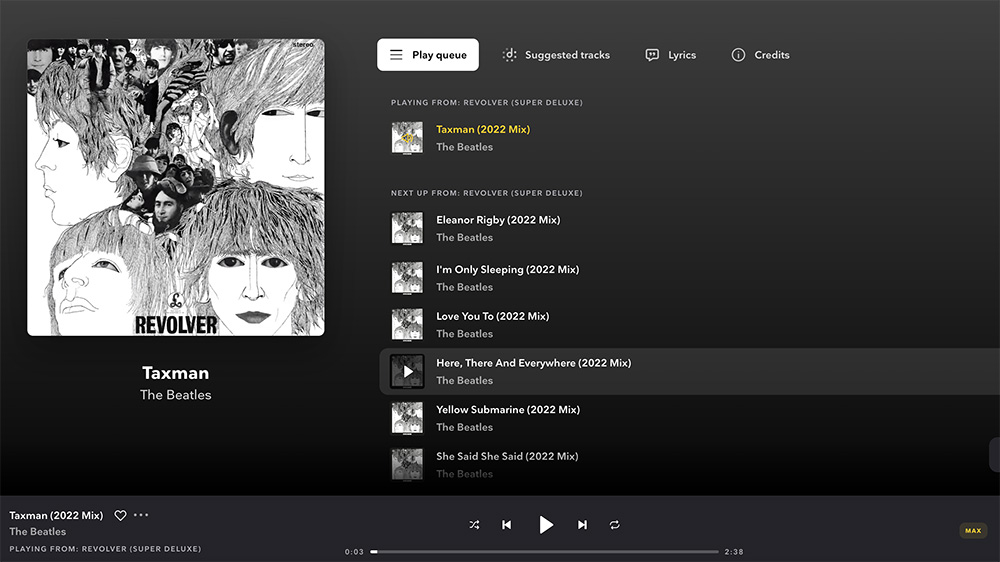

To compile the music used to compare, I grabbed a great stack of CDs from my shelf, selected a song from each, and recorded each song from Tidal. It soon became clear that the majority couldn’t be compared. Over the years there have been remasters, reissues and remixes aplenty, and often (‘nearly always’ might be more accurate!) it is not entirely clear on a streaming service which version you are listening to. And that isn’t to mention the CDs I have which don’t exist on any streaming service! For example, I have two CDs of Dire Straits’ eponymous debut album – the original I bought in 1984 around the same time I bought my first CD player, and somewhat later the 1996 remastered version. I have three CD versions of The Beatles’ ‘Revolver’ – one I bought many years ago (I think it was the first CD version), the 2009 remastered version, and the highly regarded 2022 deconstructed-and-remixed version.

Which of those five albums is on Tidal? Spoiler: it is the 1996 remastered ‘Dire Straits’ and both the 2022 (on Tidal it’s ‘Revolver (Super Deluxe)’) and 2009 (‘Revolver (Remastered)’) versions. Even then, I couldn’t use the 2022 ‘Revolver’ version for the comparison because on Tidal it is a high-resolution (24-bits/96kHz) version. The 2009 version is standard CD quality (16-bit/44.1kHz). And yes, I will get to some hi-res comparisons later…

What I ended up with was ten tracks from ten CDs across a range of genres:

- The Real Thing from the Russell Morris compilation album ‘Retrospective’ (EMI 7243 8 37320 2 9)

- The third movement – Scherzo (Allegro) – from Sibelius’s Symphony No.1 in E minor, Op.39 (Telarc CD-80246)

- Total Control from The Motels’ self-titled debut album (EMI 7484452)

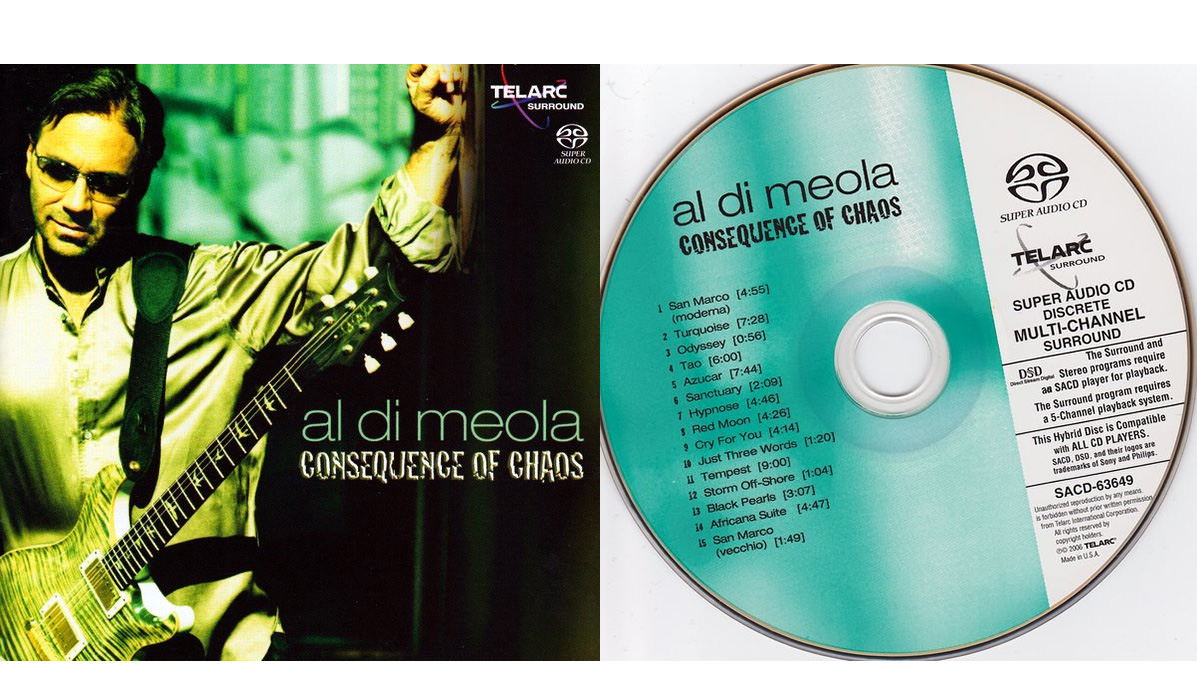

- Red Moon from Al Di Meola’s ‘Consequence of Chaos’ (Telarc CD-83649)

- Rosanna from Sebastian Hardie’s ‘Four Moments’ (Mercury PHCR-4207)

- At the End from Sebastian Hardie's ‘Windchase’ (Musea FGBG 4274.AR)

- Armando’s Rhumba from The Idea of North’s ‘Extraordinary Tale’ (ABC Jazz 476 4524)

- Six Blade Knife from Dire Straits’ self-titled debut album – the 1996 remastered version (Vertigo 800 051-2)

- Solid Rock from Dire Straits’ ‘Making Movies’ –the 1996 remastered version (Vertigo 800 050-2)

- Eleanor Rigby from The Beatles’ ‘Revolver’ – the 2009 remastered version (Parlophone 0946 3 82417 2 0)

(The codes take you to the relevant entry for each CD in the Discogs database. Even ostensibly identical versions of a CD with the same catalogue number are often mastered multiple times by different facilities in different countries.)

Tidal results

Let’s cut to the chase: of the ten tracks, seven were absolutely perfect, two had a handful of tiny differences, and one was… complicated.

By “perfect”, I mean that every single one of the tens of millions of samples on the CDs was identical to the matching sample of the stream from Tidal. That is despite the use of those old cables and the uncertain heritage of some of the CDs. For example, I picked up The Idea of North album for a couple of bucks at a charity shop.

What about the three imperfect ones? Another charity shop rescue was the Al Di Meola CD. Now, normally when buying second-hand I inspect the surface of the CD and reject any that are noticeably scratched. (On one occasion, I found a classical treasure trove at a charity store, but it turned out that the original owner had so treasured his collection that he had scratched his driver’s licence number into the surface of every single one!) This CD wasn’t bad but certainly noticeably scuffed – but I broke my usual rule because it was on the Telarc label and I love the quality of Telarc recordings.

My chosen track on that album, Red Moon, turned out to have a slight variance between the Tidal and CD versions: four samples (out of 23 million) were out by just one bit. I can’t know the reason for certain, but perhaps the scratches had left some bits obscured, and the subsequent interpolations were slightly different from what the original data was. If that’s the case, that should provide considerable comfort to those with modest disfigurements of their CD surfaces: only four errors, each of which results in a -90dB variation from perfection. Not bad.

The Sebastian Hardie ‘Four Moments’ CD has long been in my collection. In fact, it might even have been the first thing I ever bought online, from the then-new upstart American retail outlet ‘Amazon Books Inc’ (which is how it appears in my records!), back in July 1998. I’d been looking for a CD copy of this great album for years and, in the end, the only version I could find of this Australian’s group debut was a Japanese pressing, which I purchased via the US. It was almost a perfect match with the Tidal version: there were nearly 120 samples out by just 1 bit – all negative and gathered in thirteen groups. That figure might sound like a lot, but there are nearly 32 million samples in the track. This was somewhat of an enigma to me as the surface of the disc is unmarred, despite many plays over the decades. I thought that perhaps the disc was flawed (remember that old bogeyman ‘CD rot’), but I compared the new rip to the FLAC version on my server, which I ripped, according to the file information about ten years ago, and it was identical. So consider that minor difference an unsolved mystery.

The curious one was the hit track, Total Control, from the 1979 self-titled album by The Motels. It too was an absolutely bit-perfect match, except for two issues. Firstly, it soon became clear that the left and right channels were reversed on the CD compared to the Tidal version. Spotify matched the Tidal version channel-wise, so for the analysis I swapped the channels of the CD version. That resulted in a perfect match between the CD and the Tidal rip… but only for one channel. A lowish level and weirdly distorted version of the music persisted in the other channel of the file where I’d subtracted one from the other.

So I examined the waveforms more closely, and it turned out that what had originally been the left channel in the CD was delayed by one sample compared to the right channel. Weird, huh? And yes, it was clear from the mismatched peaks of the transients that the CD was at fault, not the streaming versions. Do those oddities destroy the sound? Well, having owned the CD for forty years, I can’t say that I ever noticed. Had it been an orchestral work, I would’ve undoubtedly found it odd that the violins were on the right-hand side of the soundstage rather than where they belong, but with modern music, does it matter? As for the single-sample misalignment between the channels, since it is independent of frequency, it’s a group shift, meaning it is easily counteracted simply by moving your head so that it is 7.7mm closer to the right speaker than the left. That will offset the group delay… should you happen to come across the same version of the CD that I have. Of course, I apply the traditional equilateral triangle treatment to my speaker positions, but I can’t say I’ve ever been slavish enough to my point on the triangle to have had to make this adjustment.

In any case, after swapping the left and right channels and delaying one of the channels by one sample, the result was a bit-perfect match.

Spotify results

Let me be clear, I’m not planning to get into the contested field of sound differences here; all I am trying to do is quantify the differences and provide a sample of what they sound like. (Obviously, there’s no point in providing those samples for the Tidal tracks, because they would consist of nothing but absolute digital silence!)

So, how indeed have I quantified the differences? I’ve used the Cool Edit software to determine the differences in level, expressed in decibels, between the peak level of the original track and the peak level of the CD-minus-Spotify version, as well as the differences in levels between their average levels.

For the peak levels, the differences averaged across the ten tracks (weighted by track duration) was 25.5dB, with a range of 23.9 to 27.7dB. I suspect, however, that the average levels are more representative, considering you might just have one peak sample, with all the rest well below it. The average (duration weighted) was 32.6dB, with a range from 30.7 to 36.0dB, below the average track level.

Interpreting this is difficult. Again, I stress that what I’m talking about is not stuff being added to the signal, such as harmonic distortion, nor even subtracted from the signal, but indeed a variation from the signal determined by the Ogg/Vorbis compression algorithm that Spotify uses. That said, and just to give a sense of proportion, if total harmonic distortion is at -32.6dB, it would be stated as 2.3 per cent. And for the peaks, -25.5dB would be stated as 5.3 per cent.

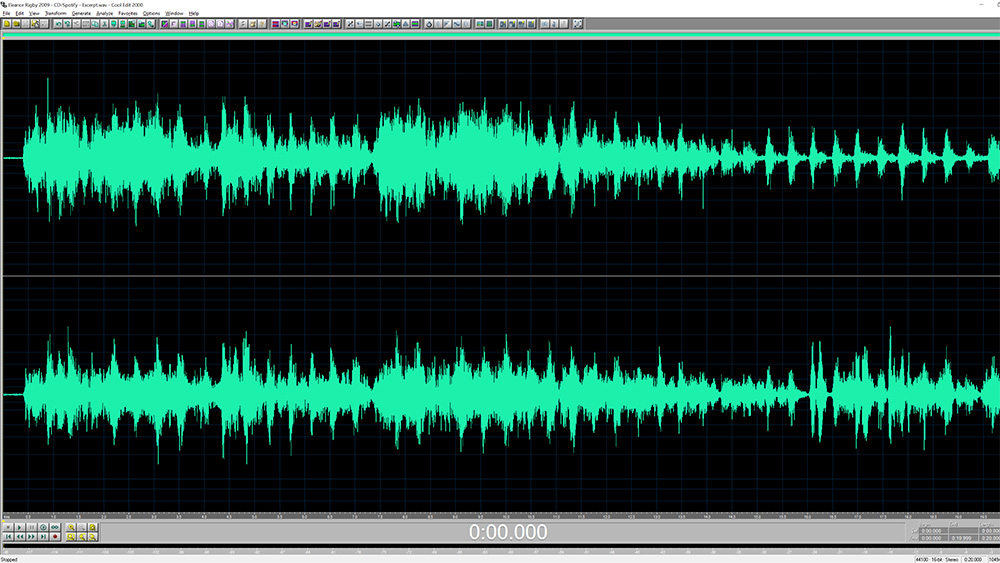

The graphic above illustrates the result of subtracting the Spotify version of Eleanor Rigby from the CD version, significantly zoomed in vertically so that you can see things clearly. (Check the scale on the right-hand side; the full scale is 0dB, but the graphic only shows up to around -24dB.)

I could, if you were wondering, hear this difference in the signal, which I've captured in this twenty-second clip. Warning: it has somewhat of a horror movie feel – think The Omen or The Exorcist. If you want to compare, just play the first 20 seconds from the appropriate version on Spotify, Tidal or the CD. Again, this is not what is missing from the pure original, but indeed the difference between the Spotify and CD versions. It may be additions as well as subtractions.d

What about hi-res songs?

One thing no one can dispute is that Spotify offers no hi-res audio while Tidal has quite a lot of hi-res content. As it happens, I have gathered quite a bit of hi-res content over the years – from DVD-Audio, DVD-Video and Universal’s Pure Audio Blu-ray series. But I couldn’t find a match between any of Tidal’s hi-res content and mine. In fact, the differences were very obvious, usually involving completely different levels. Perhaps that isn’t surprising since the music that finds its way into hi-res treatment, and which the various record companies troubled themselves to release on such formats as DVD-Audio, was precisely the kind of music that has attracted careful remastering over the years.

But my efforts weren’t entirely in vain. Amongst my hi-res tracks were quite a few which, I confess, I acquired by downloads from various sketchy sites, or imported from high-end servers and digital media players I’ve reviewed. It turned out that at least five of these were kind of identical to the Tidal versions.

These are the tracks I used:

- Aqualung from Jethro Tull’s ‘Aqualung’ – 24-bit/96kHz

- Last Exit from Pearl Jam’s ‘Vitalogy’ – 24-bit/96kHz

- Tower of Babel from Elton John’s ‘Captain Fantastic and the Brown Dirt Cowboy’ – 24-bit/96kHz

- Respect from Aretha Franklin’s ‘I Never Loved a Man the Way I Love You’ – 24-bit/192kHz

- Davy from Marlena Shaw’s ‘Who Is This Bitch, Anyway?’ – 24-bit/192kHz

So, why ‘kind of’, and not completely, identical? Well, in every case they differed only by variations of minor significance: the quantisation level was out by one for around 50 per cent of samples. Since they were all 24-bit tracks, that means one out of 16,777,216. It was clear that one or the other versions of each track had been dithered (i.e. there was a random zero or one was added to every sample). Not both, though, because that would have resulted in a significant number of 2s, not just 1s.

Of course, 1 bit of dither results in, at worst, only a white noise at -138dB, which is several orders of magnitude below the noise floor of all the equipment used both in the production and playback of the music, so for all practical purposes these also were identical.

Conclusion

I don’t think there is any objective way to map differences in the digital audio that my examination revealed to any specific differences, if any, in how Spotify might diverge from the CD in sound quality. My interest in losslessness is driven by the fact that while Spotify might or might not degrade sound quality, you can be completely confident that true lossless sound from Tidal involves no degradation.

If you’d be just as happy playing, say, a CD-ROM of MP3 tracks in your CD player as the original CDs from which those tracks were compressed, this article isn’t really for you.

But if you want to be reasonably confident that the source of your digital audio playback is as good as it can be, my tests suggest that you can have that assurance with Tidal.

MORE:

Hi-res music streaming services compared: which should you subscribe to?

Tidal scraps MQA and spatial audio format

Tidal vs Spotify: which streaming service is best for you?

- Jez FordEditor, Sound+Image magazine