This overrated hi-fi feature is an excellent concept poorly executed

EQ delivers sound as you like it, but not without repercussions

A high degree of due diligence comes with reviewing hi-fi (or anything, for that matter). Every feature that the subject of your testing has onboard should be tried out, even if your assessment of them all doesn’t make your written review because some are, as is often the case, ordinary, work as intended and not worth taking your carefully penned review to novella length (we’ve all endured those, haven’t we?)

I’ve been reviewing hi-fi for over a decade, and I still enjoy it as much now as I did all those years ago when I was learning my dipoles from my bipoles (everyone has to start somewhere…). I mostly enjoy it, anyway. Every job has its downs, of course, and while some of my colleagues may loathe the unboxing and reboxing element or perhaps having to write a negative review, my disdain in the process is testing an audio product’s EQ (equalisation) adjustment.

EQ is a great idea

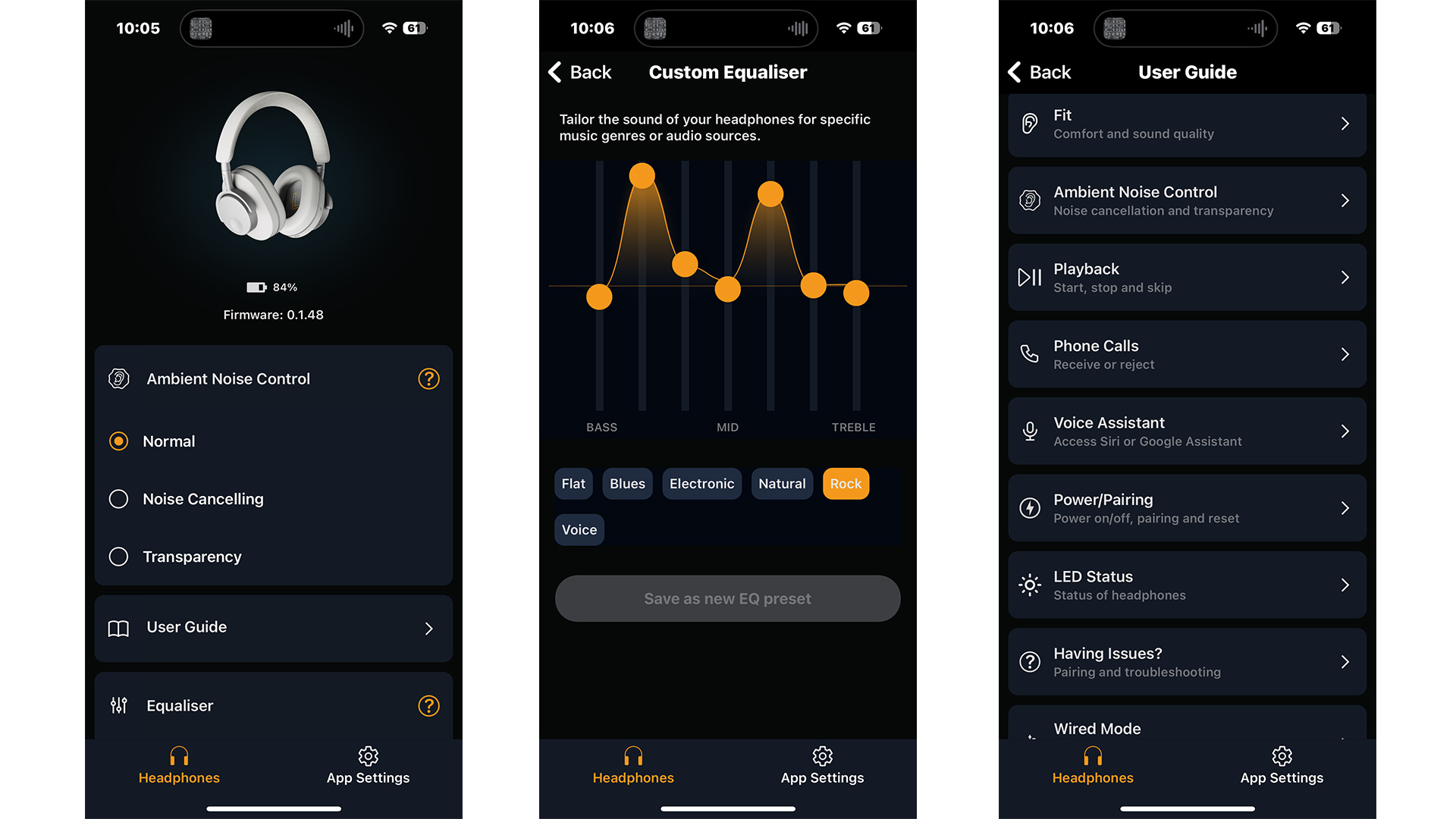

For the uninitiated, an ‘equaliser’ essentially allows for the adjustment in volume of parts of the audio signal’s frequency bands; you can cut some or boost others. The equalizers typically found in audio kit and headphones can be ‘bass’ and ‘treble’ tone controls at their crudest, or offer several steps of ‘+’ and ‘-’ dB adjustment for various different frequencies (200Hz or 1Kz, for example). This graphic equalisation lets you increase and decrease frequencies either within a set band or above or below a certain frequency. (There are more sophisticated and versatile parametric equalisers that let you choose the centre frequency of each band and the exact levels you want to boost or cut by, but these aren’t the ones I typically come across or what you’ll find in your new pair of wireless headphones.)

Essentially, equalisation gives the product user an easy way to tweak the sound to some extent to suit their preferred balance. If they want less bass they can cut the bass frequencies. If they want more vocal they can slightly boost the midrange frequencies (and preferably also slightly cut the others). If they like a ‘V’-shaped EQ (prominent bass and treble, recessed mids), they can turn the dials to get that too. Or if someone’s listening room has a big peak in the bass they want to compensate for, EQ could to some extent help (although physical acoustic room treatment or room correction DSP would be much more effective here).

Now, I like EQ. It’s a great idea and its attraction is plain to see, particularly in a modern world that increasingly values and strives for personalised experiences. I’ve heard EQ work effectively several times on several hi-fi components – both digital and analogue ones, and not exclusively high-end stuff. For example, I use a Chord Mojo 2, a relatively affordable DAC in the scheme of things, and its four-band EQ does the job and adds value to the product.

The thing is, pretty much every time I’m faced with Bluetooth headphones or a wireless speaker (or similar) and the time comes to tinker with its EQ settings, more often than not via touch-screen sliders in an accompanying app, I fail to be inspired. I can’t remember a time when I preferred the sound when those sliders were anything but in the middle, regardless of whether I liked that product’s out-of-the-box tuning. In my mind, EQ is the In Time movie equivalent of today’s audio products: excellent in concept, poor in execution.

It's all in the implementation

Akin to manic multi-tasking, EQ adjustment can be both helpful and harmful at the same time; by making one thing subjectively better, something else inevitably suffers. Not everyone likes a tonally neutral or even or flat (call it what you like) sound, but personally I do. So when I’ve encountered headphones or speakers with, say, a peaky treble or overpowering bass, I’ve used their EQ adjustment in an effort to neutralise that balance a little, only to find that by ‘enhancing’ one element, others are screwed up. And often that spoiling is audible. It’s hard to put my finger on at times, but in my experience significant EQ adjustments can affect rhythmic drive and make the presentation a little thin and lifeless. Of course, besides that, there is also the fact that if a product is, say, too rich in the bass or it has a quality you don’t like, lowering its level won’t improve its quality. Shifting the tonal balance doesn't fix any issues in the sound.

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

The school of thought is that anything you add to an audio signal will somewhat degrade its purity – indeed, no hardware can ever technically better the original signal. An EQ inherently shifts phase: frequencies pass through the filter at slightly different speeds and cause small time delays in the signal that ultimately alter the frequency response and result in more noise and distortion. (Even digital ‘Linear Phase’ EQ, which was designed primarily to avoid screwing up phase, has its own sound-affecting consequences.) But when an EQ tool is well implemented in hardware, those repercussions are less discernible by ear.

So why is such a universally adopted feature of your more ‘everyday’ digital audio products widely imperfect? I asked the lead engineer at one of the most reputable British hi-fi companies, which makes everything from modest wireless headphones and speakers to high-end passive designs, that very question, and his answer enlightened me. It might enlighten you too.

He suggested that in such devices, the EQ would typically be implemented in DSP (digital signal processing). That in itself is fine – he actually argues that properly applied DSP has the edge over analogue EQ, particularly if that EQ is made to be customisable – but that the lower-cost processing chips generally at the heart of their design don’t have processing power on tap, and that tends to have a knock-on effect on how precise the DSP software is and how critical it becomes for the EQ to be carefully programmed. Whereas a decent mid-level chip that you might find in a pricey active speaker might immediately convert each sample of an incoming audio signal at 32-bit and perform any DSP calculations at 64-bit, a lower-power chip may not have that same raw bit depth to play with and thus cannot make as precise DSP calculations – especially if we’re talking about a single-chip design for headphones that also has to handle all the necessary processing concerning Bluetooth, active noise cancellation, controls and whatnot.

He said that digital processing (like that needed for EQ) doesn't necessarily need to sound poor on low-power chips, however, remembering that in the 90s high-end audio companies managed to implement DSP on them well, using their own digital wizardry to overcome any lack of bit depth. Presumably, today’s chip manufacturers aren’t adopting such tricks in their software, so EQ adjustment could indeed be tricky for audio companies who reasonably use low-power processors for relatively modest kit to implement well.

I hope for improved execution in the future as, to repeat my earlier sentiment, being able to flavour your sound to your palette effectively and without consequence is hugely appealing. You could, of course, argue that buying good kit with the right balance for you in the first place – and accepting that not all album recordings will be mixed to your preference – is the best approach.

Of course, if to your ears the benefits of your EQ adjustment outweigh the drawbacks, roll with it; your own ears should always guide you.

MORE:

What is high-resolution audio? And is hi-res music worth it?

7 common mistakes to avoid with your stereo amplifier

Is there really a ‘right’ hi-fi sound for different music genres?

Becky is a hi-fi, AV and technology journalist, formerly the Managing Editor at What Hi-Fi? and Editor of Australian Hi-Fi and Audio Esoterica magazines. With over twelve years of journalism experience in the hi-fi industry, she has reviewed all manner of audio gear, from budget amplifiers to high-end speakers, and particularly specialises in headphones and head-fi devices.

In her spare time, Becky can often be found running, watching Liverpool FC and horror movies, and hunting for gluten-free cake.