The story behind Helix, the most accurate audio playback device today?

If it's good enough to have been adopted by Stanford University as its audio reference to analyse vintage recordings from the Smithsonian archive, it's good enough for us!

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The story of the new Helix began when a Qantas first officer met an aeronautical engineer absorbed in solving structural resonances in aircraft.

It was the ideal background for engineer and inventor Mark Döhmann, who has arguably developed ‘the most accurate audio playback device today’. And that isn’t just an idle claim made by certain audiophiles, so it appears. The Helix was recently adopted by Stanford University as its audio reference to analyse vintage recordings from the Smithsonian archive. It also won Golden Ear awards from online publication Positive Feedback – an appropriate award given that ‘helix’ means the curved edge around the top of the outer ear. In this case, it spelt the DNA of success.

Döhmann said kudos should go to his business partner, George Moraitis, whose financial backing freed him from mundane obligations to concentrate on R&D – a big step for audio kind it seems, and, he said of this instance, not possible without Moraitis’s direct input. Moraitis is a senior-pilot-turned-electronic-supplier-to-government-power-grids, owning an IT test and measurement business called Fuseco, which supplies sophisticated electrical parts and logistics to government power utilities as well as big business.

But notwithstanding that, Döhmann sells himself short. “I began as a sub-teen dismantling turntables, before building my first ‘table at age 16 under the practical guidance of my aero engineering father,” he said. “The payoff has been flattering, it’s been my life since I was a kid... I’m now 56 and those plaudits come after countless years of dedication to this one pursuit.”

Stanford University chose the Helix turntable unprompted, without Döhmann’s knowledge, over feted alternatives from Clearaudio, Kuzma and Goldmunds etc. This choice may well have led to the Helix leapfrogging competitors as the standard bearer for front-end detail.

“The turntable is the most critical stage of sound reproduction, proving the adage ‘rubbish in, rubbish out’”, said Döhmann. “They [Stanford] chose it but requested some adjustments.

“Some of those historic recordings were recorded at various speeds so we supplied them with 16-inch and 12-inch platters, with zero to 100rpm capability. They can now hear exactly what is in those historic recordings; there’s no shaping or smoothing to hide flaws ... so it’s not inter-modulating or adding to the original sound. The cartridge choice, however, is chosen for the emotional connection. It’s Stanford’s choice.”

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

Carl Sagan and ethno-musicologists, like those at Stanford, selected the recordings sent on the Voyager 77 spacecraft to represent the music of the human race. Aliens haven’t responded yet, but Stanford has a better understanding of what is in the grooves they’re listening to.

Not surprisingly, the Helix turntable somewhat resembles a space hovercraft – a landing module, if you will. In fact, the silence of outer space is mirrored in the Helix: its silent accuracy reveals every detail of those gold-plated recordings, such as Stravinsky himself conducting his Rite of Spring, Blind Willie Johnson’s Dark Is The Night, Chuck Berry singing Johnny B. Goode, and so on, among other treasures on board such as the earliest folkloric recordings by Alan Lomax and Sam Charters. The Helix will now voice the great American songbook of vernacular music in future. No Kraftwerk cheeseburger electronics here.

It is said that the ingenuity of the Helix design could not have evolved inside a turntable factory. “This knowledge comes from a whole other place,” said Moraitis.

Moraitis studied physics prior to piloting passenger aircraft. At the time, Döhmann was effectively a flight engineer diagnosing the type of faults that Moraitis was logging in the cockpit. The two of them were established players in their respective fields. In December 2017, they officially joined forces with accounts manager Jim Angelopolous to form Döhmann Audio. Meanwhile, Moraitis and Angelopolous independently run high-end importer Nirvana Sound where Döhmann Audio is based. The Helix crew work together with audio technician Dallas Clarke, who is respected for his electronics expertise.

“Our business is differentiated from other developers by our joint experience in science and aerospace,” says Moraitis. “It’s not common in this industry to have that background, and meeting Mark was serendipitous. We shared the same passions – aeronautics and audio/hi-fi – and for many years, before meeting, we led parallel lives.”

Their symbiotic understanding is both personal and practical. Neutralising noise and vibration up in the air, Mark says, is not scientifically dissimilar to neutralising it on the ground. “And we’re good mates to boot!”

Australian HiFi: Why did you choose a belt drive design?

Mark Döhmann: We chose belt drive over rim drive and direct drive because we could better control resonances and speed variations. We have instruments at Fuseco to measure performance, keeping everything in-house. For example, our microscopy techniques to measure resonances in the power industry are applicable in developing a turntable.

George Moraitis: “We call it resonance mapping – identifying where those sources are. Theoretically, the only vibrations should be where the stylus hits the grooves. Whereas in reality, when you’re placing vibrational measurement devices all over the chassis and arm board etc, you realise there’s interference from all over. The aim is to eliminate those sources, particularly with the arm board. Simply suspending it in the chassis is not enough.”

AHF: So that’s when you investigated alternative materials for the armboard?

MD: We found a polymer used by Texas company to make bulletproof vests and armoury. That polymer transfers energy at 90 degrees. We use that molecular structure to divert any resonances moving up the armboard to 90 degrees away from the cartridge and stylus. It’s a huge breakthrough in military applications, which is relevant to us.

AHF: So issues commonly arise from the choice and application of materials?

MD: If you use a homogenous material, such as an alloy, you’ll get a predictable result. But if you construct the armboard as a layered sandwich of three different materials, you will get different behaviour as the vibration entering the armboard transmits to the top level, where the arm is bolted.

The arm is only connected to the record by the stylus, so the vibration travels up the arm from the stylus (‘chatter’ they call it), then you have the noise generated in the bearings by not handling that vibration – if, for example, they are loose – then you have your motor and bearing noise which is trying to tunnel up the armboard and come down the arm into the cartridge, which then modulates the cartridge and gets re-amplified.

AHF: Those early years of tinkering were critical it seems...

MD: Yes, at the airlines I spent years examining composite structures – like carbon fibre, plastics, composite materials, fibreglass – plus metal analysis such as metallurgy, machining to blading, stress analysis, sound reduction and vibration. As you know, things rattle and get loose in aeroplanes, and all of this understanding is handy in audio manufacturing.

AHF: So who assisted you in manufacturing your first turntable for commercial sale?

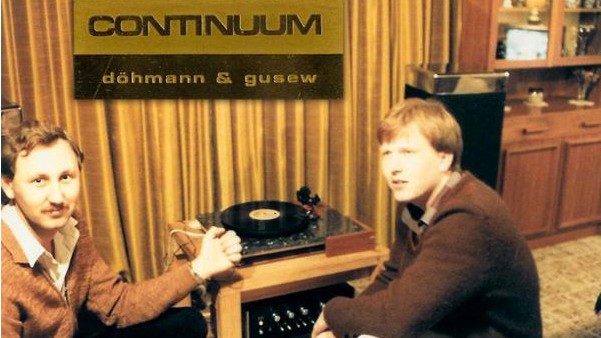

MD: Audio Trends did retail for me. Swimming against the tide of CD, they gave me the keys to their gear room and, upon hearing my turntable, they supported me at age 18 in the marketing of the Continuum, built with Mark Gusew; he did the motor and electronics and I did the machining.

I used the airline’s resources at Ansett, during the strike period in the mid-80s, to work after hours with their machinery to further develop that turntable.

When I did IT computer programming, I used Materials Engineering knowledge to replace metals for a plastic, a plastic for a composite. John Veets was my mentor there, an expert in ME who trained me in isolating the noise or vibrations I was detecting via oscilloscopes etc.

The armboard is critical but so too is the suspension. [Döhmann explained that the core of the Helix models is the Minus K negative stiffness system located in the base. The spring-loaded device sits below the massive platter, distributing the load around and within the chassis, allowing higher frequency vibrations to better dissipate. The motor, platter bearing, and armboard are on separate, interlocking plates to best isolate the stylus and record.]

Aeronautical engineer Dr David Platus, of California University, invented the Minus K shock absorption system for lunar landing units and for use in bio-medical equipment. Essentially, Minus K is a system by which objects hover just above collapse, effectively isolating. Its natural frequency is extremely low. For example, if the natural frequency is half a hertz (0.5Hz), the ground has to move at half a hertz in order for it to oscillate. If it is two hertz (2Hz), the half a hertz sitting under it won’t be affected; it’ll absorb the movement and isolate it ... so footfall, plant and equipment noise, road traffic, earth vibrations are absorbed. If you put sensitive equipment, like an optical microscope, or electron microscope on an object, it remains perfectly stable. It’s a revolutionary isolation mechanism.

AHF: You said earlier that in audio, isolators are confused with dampers.

MD: Yes, they are very different. Dampers hard-couple and fix movement. Minus K is an isolator, not a damper. It works from a third of a hertz (0.33Hz) to 100 Hz, getting rid of the vibrations at that floor born level. It’s a passive system. But turntables have other inherent noise-making systems that are of a higher order, so you need different absorption, dampening or isolation systems for those frequencies, which are all active systems.

Our 100Hz mechanical crossover system creates a smooth continuous pathway to channel vibrations of higher frequencies, away from critical areas on the turntable. The proprietary TDS technology uses a pre-stress accumulation release (PAR) strategy to isolate and dissipate vibrations inside the chassis.

[Döhmann said the Helix accommodates most quality arms but he recommends The Reed from Lithuania and the Schröder CB. It’s not a sonic choice between them, though; it’s a matter of set-up. The Reed 5A is adjustable and easier to use Schröder. But any quality arms, such as the Kuzma, SAT or SME, will suit.]

Helix background

The first Helix One followed the original, 2005-released Döhmann Continuum turntable in 2015 and received a great response at the High End Show in Munich. It has since undergone three iterations as new technical improvements have surfaced (Helix One Mk 1-3). The less costly ‘domestic’ model, the Helix Two, which incorporates those same upgrades, also has three versions.

The new Helix One Mk 3 ($100,000) and Helix Two Mk 3 ($58,500) are upgradable from the Mk 1 through to the Mk 2 and Mk 3 of each. The Helix Two Mk 3 ($58,500) has the “full suite of the technology” reduced to a smaller physical footprint, with a facility for one arm only (compared to the Helix One’s two armboards) and a smaller chassis to suit smaller living areas.

The Helix is a laboratory-grade instrument in a field of sophisticated ornaments, and is a supremely neutral platform from which to launch a hi-fi system of the highest calibre.

Its Döhmann motor is an exemplary high-torque design, with a platter controlled by a motor closed loop servo located in the base. It monitors and calibrates speed more than 130,000 times a second. The motor and platter bearing are on separate interlocking plates, while the armboard consists of a new energy-diffusing composite material. A new stabilizer minimises bounce back when changing records. The core of the Helix is the MinusK isolation system, a spring-loaded mechanical device at the heart of the unit.

Since moving the operation to Australia from Europe, all Helix models have serial number control, stricter quality check processes, a verification video of the finished assembled product before issue; plus packaging details, batch control, each part traced to plating and machinery shops locally, dated and registered.

MORE:

10 of the world's most expensive turntables

Australian Hi-Fi is one of What Hi-Fi?’s sister titles from Down Under and Australia’s longest-running and most successful hi-fi magazines, having been in continuous publication since 1969. Now edited by What Hi-Fi?'s Becky Roberts, every issue is packed with authoritative reviews of hi-fi equipment ranging from portables to state-of-the-art audiophile systems (and everything in between), information on new product launches, and ‘how-to’ articles to help you get the best quality sound for your home.

Click here for more information about Australian Hi-Fi, including links to buy individual digital editions and details on how best to subscribe.