How Spotify saved the music industry but left some genres behind

Classical music streaming service Primephonic is stepping in to fill a void…

At the turn of the millennium, the music industry started a steady 15-year descent into a ditch. Music piracy had taken it down a hole and removed the rope. Thankfully, Spotify (and its streaming service rivals) arrived like a tow truck rescue team to slowly, but surely, help pull it out.

Today, streaming has a 46.9 per cent share of global music industry revenue (IFPI) – in the US, that figure is 75 per cent – and virtually all revenue growth. Five years after Thom Yorke described Spotify as “the last desperate fart of a dying corpse”, 2018 saw the third consecutive year of double-digit growth for the industry, mostly thanks to streaming.

But the green giant’s streaming model, and that of its established Apple, Google, Amazon and Tidal rivals, hasn’t just affected the way we consume music. It has altered what we listen to, how music artists get paid, and even how musicians make music. The problem is that some of the more niche genres, such as classical, are being left behind.

Under-represented

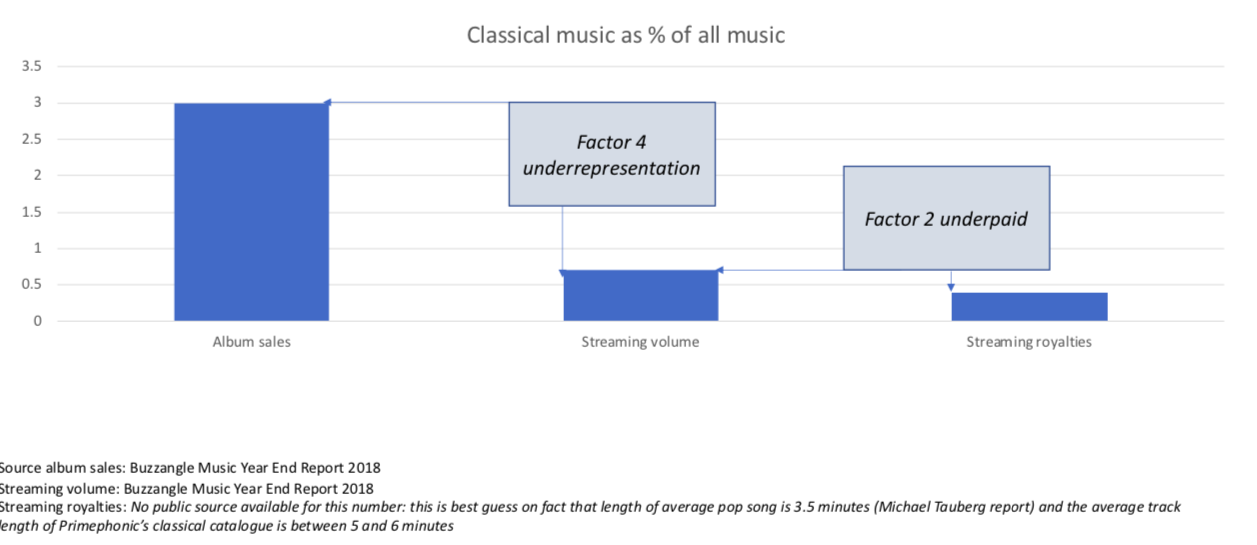

Classical music makes up five per cent of the music industry’s total output – okay, perhaps not a staggering revelation – but it is hugely under-represented in streaming, making up just one per cent of all streaming and only 0.5 per cent of streaming revenue.

About a quarter of classical music consumption is via streaming (BPI), with the rest being vinyl, CD, downloads and radio, while in pop music that’s over half. If mass-market services rescued pop music, classical has yet to feel the same effects of the recovery.

That displacement of classical music in the streaming sphere could have huge ramifications for the genre. According to recent Goldman Sachs forecasts, 1.15bn people around the world will be streaming subscribers by 2030 (it’s currently 255m, according to IFPI) so that under-representation could be exacerbated in the future.

So how has this happened? Thomas Steffens, CEO of Primephonic, a relatively new but ambitious classical music streaming service, attributes it to Spotify’s model, which he says doesn't work for classical.

Get the What Hi-Fi? Newsletter

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

A one-size-fits-all model

"Spotify is designed for pop music," says Steffens. "It’s smart, it tries to get you to listen to new, upcoming tracks, so you can stay on top of trends that come and go. But most classical music is 200 to 300 years old. Being introduced to new stuff isn’t what classical fans care about. They want to listen to stuff they haven’t discovered yet, basically unknown work, which is the opposite to Spotify’s algorithms.

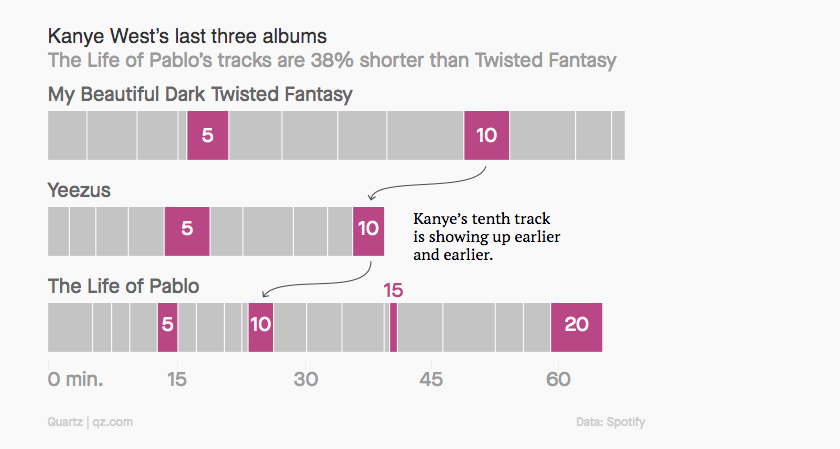

"Spotify’s model works well for pop music. You pay £10 per month as a subscriber. £2 is VAT, 60 per cent goes to rights holders and the remainder goes into the artists pool. At the end of the year, the streams are counted and pay out is based on how many times you’ve been listened to [Spotify pays per stream, which counts if someone listens to 30 seconds of a song].

"You can listen to lots of three-minute Rihanna songs in an hour, but those listening to longer classical works – say, a 20-minute Beethoven movement – can only fit in a few per hour. So here, Rihanna gets many times more royalties than the orchestra does." You can see the logic.

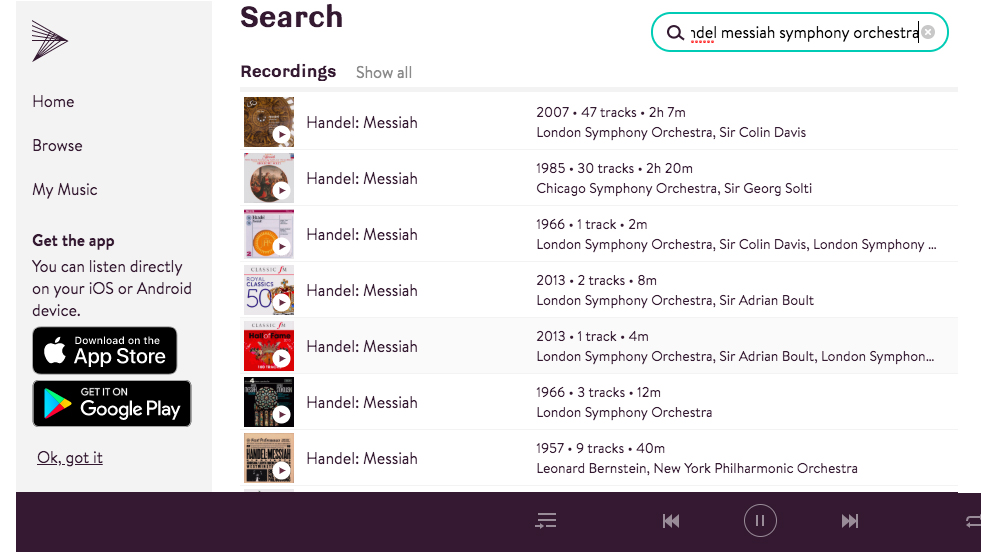

It’s not just the pay-out model or the algorithms that are hurting classical music, but also its accessibility. It’s not that it isn’t there, it’s just not always easy to find on the popular streaming services. Rather than simply being searchable by song, artist or album name as most music is, classical music is, uniquely, identified by various metadata: work, recording, composer, performer, conductor… you get the idea.

Search for a specific work, such as ‘Elgar Symphony No.1 London Philharmonic Orchestra Vernon Handley’, and you'll get coherent results in Spotify. A less specific search of, say, ‘Handel Messiah symphony orchestra’, however, brings up a long list of albums – it isn't instantly clear as to which recording you’re after, unless you’re familiar with the album art. The work conducted by Colin Davis? Or Adrian Boult? It's a bit like hunting for a particular brand of large blue sweatshirt in a jumble sale only sorted by size.

"Labels provide DDEX data for every album, but what you need is the album data, and then the data of all the works," says Steffens. "Our team has been making a database of all the classical works in the world and all the data fields, composer by composer. With Bach, it took us a week, and we've now done it for 1,700 composers. Ten people have been working on this manually for a year and a half to get the metadata correct. Spotify has one worldwide editor specifically for classical, and that vacancy has been open for a year. Here, there are 28 editors," he adds.

Indeed, Primephonic lists composer and release date, shaving a few seconds off the hunt that, in an evening listening session, could easily amount to minutes.

An impacted genre

"The longer the work is, the less you get paid per minute, so contemporary composers have a perverse incentive to compose shorter works," Steffens notes. "Some labels are even cutting works into two or three parts to benefit more. If the whole industry starts to ignore longer works, such as Wagner’s, that changes the genre. It was never Spotify’s intention, it’s just a negative side effect of a formula designed for pop music."

So, for example, to work to that model and get the payout-per-stream it deserves, Gustav Mahler’s 100-minute long Symphony No. 3 would have to be 30-odd tracks, with the first of its six movements alone cut into 10. Ouch.

However, it is worth noting that pop music is also experiencing this knock-on effect. From 2013 to 2018, the average song on the Billboard Hot 100 fell from 3 minutes and 50 seconds to 3 minutes and 30 seconds (Quartz).

Steering away from a cliff edge

“Spotify has tried to fix it, but it has other priorities, such as the India launch, podcasts and voice control – classical music isn’t one of them right now, so it doesn’t get the resources it needs,” Steffens says. "But even if Spotify fixes it, there’s still the same problem on other services.”

Recognising that Spotify and other leading streaming services have created a whole new platform that has replaced download stores, radio channels and CD stores for many genres, Primephonic has been created as a lifeline for classical music. Its mission is to do for classical what Spotify did for pop music – and as Beatport is trying to do for dance and Quincy Jones’ Qwest TV is doing for jazz.

“We’re moving towards a streaming-only world. If classical music is to survive, it must fix the problem, otherwise it’ll lose its relevance. It might not be a problem today or tomorrow, but look ten years ahead and there’s an existential problem,” Steffens says.

“We’re trying to capture the classical music space. With video streaming, we’re seeing some services for arthouse movies because Netflix can’t have everything, so they focus on winning mass markets. Niche services are coming. The more subscribers Primephonic gets, the more money we have to pay royalties to artists. That’s how we steer them away from a cliff," Steffens says.

As streaming rises and rises, arguably there is a broader, more exploitable landscape for niche services to emerge. But we’re talking about a relatively new service with currently around 50,000 registered users and a limited global reach (UK, US and Netherlands, with a global rollout planned for the summer), compared to Spotify’s 100 million plus paying subscribers worldwide.

Will classical music fans be willing to pay for a second monthly service, or be dedicated enough to choose only Primephonic and forego other genres? Will Spotify up its classical game and change its model in the future?

While Steffens is unequivocal in his passion-filled purpose, he admits that classical streaming could be better off in the hands of a bigger beast. “If we prove it can be fixed, and that there’s a willingness of people to pay, I can imagine one of these services acquiring us. Ultimately, it could be best for classical music if we were acquired by one of the big guys, because they could expand our technology to a bigger audience than we could ever do ourselves,” he says.

Whatever the fate of Primephonic and Spotify, streaming looks set to be the future of music consumption – and the classical music genre has to find a way to keep up.

MORE:

Becky is the managing editor of What Hi-Fi? and, since her recent move to Melbourne, also the editor of the brand's sister magazines Down Under – Australian Hi-Fi and Audio Esoterica. During her 11+ years in the hi-fi industry, she has reviewed all manner of audio gear, from budget amplifiers to high-end speakers, and particularly specialises in headphones and head-fi devices. In her spare time, Becky can often be found running, watching Liverpool FC and horror movies, and hunting for gluten-free cake.