Listening to the intriguing, immersive and divisive Iris Flow headphones

The 'shaped by Iris' sound is realistic, but won't be for everyone

Tourists and frenetic shoppers are largely absent from London’s once-buzzing Oxford Street. Precious few white-collar commuters are scouring its numerous cafe chains for a sandwich either – welcome to summer 2020.

Add to this the fact that the temperature just tipped 34 degrees in the shade and it makes for an altogether sleepy afternoon on London’s main retail thoroughfare. That is, until we get to the third floor of a striking art deco building just off the main drag. Iris HQ is a hive of activity encased in glass, wood, clean white walls and glorious air conditioning.

We’re here because Iris, a relative unknown in the audio world, recently launched a pair of wireless headphones with a new piece of intriguing, but divisive, sound tech built-in. The company also made the algorithm available as an app that you can trial on its website. We’re not alone in wanting to hear more; early Iris adopters include Queen drummer Roger Taylor and Concord, an independent music company.

Jacobi Anstruther-Gough-Calthorpe, Iris founder and CEO, is proud of these initial investors. Concord is typically cautious of such endorsement – and to hear Brian May and Roger Taylor say that they’re finding things in Queen recordings that they hadn’t noticed before is no trivial statement.

What is Iris? It's a patented algorithm that "unlocks and resynthesises lost audio information in a recording, allowing the listener’s brain to play an active role in piecing it together, recreating the original live music experience”. So is it just another immersive tech to rival Dolby Atmos? Actually, no.

To explain why though, we need to drill down into the tech a little further. Iris’s algorithm uses a mathematical function known as a transform, which is all to do with the sound waves we hear.

If you wore a blindfold in a cathedral, you’d be able to tell if a baking tray were placed above your head. The sustained reverb of the stone walls would be cut short, replaced with those bouncing off a metallic sheet. It's an odd image, maybe, but an example of how the sounds we hear are not only transmitted directly from their source to our ears, but also from the surfaces of our environment.

Get the What Hi-Fi? Newsletter

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

Our brains know and expect natural sound to arrive from multiple directions, at different times. It processes these almost entirely subconsciously – unless you remove another sense, such as sight.

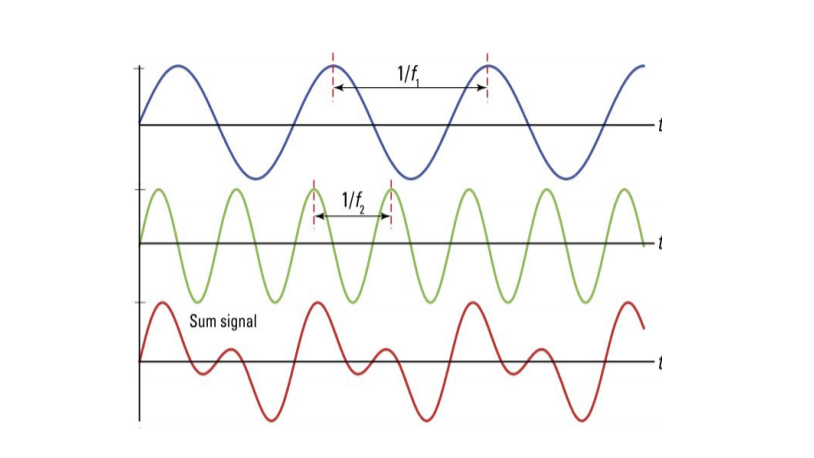

However, a microphone doesn’t capture the wide, stereoscopic array of separate phase relationships bouncing around it, only the sum of what they add up to. The metal disc inside the microphone cannot move in its ‘forwards’ and ‘backwards' phases at the same time, and so it captures the compromise between the two.

In the graphic below, imagine that the blue signal is what your left ear hears, the green signal is the right ear. The microphone won’t pick that up; instead, it records both together, shown by the red signal.

Enter the Iris algorithm: essentially, it aims to unpack these frequencies and split them up. With the transform, Iris says it’s possible to rearrange the data in the audio stream and reveal detail that was previously hidden.

These transforms work back from the information available, to resynthesise the individual signals that constituted it. Iris says its transform runs a filter for every possible frequency, to discover which of them, and in what amounts, make up the tangled signal.

Using proprietary technology to reconstruct the previously discarded phase dimension of the original sound, it then presents each opposing ear with new phase information for the brain to resolve. Iris engineers claim that the tonal balance of highs, lows and mids of the original signal is entirely preserved and unaltered.

What about limited bandwidth, storage and data allowance? Crucially, Iris technology is applied at the audience end (the user’s device) so the newly upscaled audio doesn’t have to be stored as a huge file or transported anywhere.

Iris was initially available as an iPhone and Android app earlier this year. As a Spotify or Apple Music user, all you need to do is click through the Iris ListenWell app and let it run its filters to unlock all of that hidden phase information in your favourite song.

Until now, the app only allows limited access to Spotify or iTunes music, but the company’s inaugural pair of over-ear wireless headphones are almost ready, meaning all of your music can be heard with Iris. It’s the only product with the algorithm currently built-in – and we’re about to be one of the first to listen to them.

There’s no escaping it though: Iris’s stance is a strong one. It involves concepts such as “Active Listening”, wellness, and “re-educating” consumers to discard the EQ app support and ANC toggle on their new cans in order to better enter the flow state – hence the name of the headphones: Iris Flow.

Sound engineers, producers and listeners wedded to certain recordings may also find the company doctrine jarring; Iris was recently shown the door at a London recording studio simply for presenting its new technology. Then again, innovations and the painful truths thrown up by them mean such concepts are often initially opposed. After all, Britons once fought the invasion of coffee over their beloved traditional morning tea.

Jacobi, whose background as a music producer and entrepreneur quickly led to what he calls an “obsession” with changing how music is recorded, compressed and consumed, shuns the term audiophile (“If I were, I’d listen to analogue on wired headphones only,” he says).

However, he does want to challenge what he calls the “layers of parlour tricks” used in both the actual recording process and the digital equipment we’re using to listen to music. These include extensive mixing, compression to lossy files, EQ alterations, active noise-cancelling anti-phases, and bass-heavy crossovers. The aim is to bring a more live, visceral experience to every listener.

As we talk, he’s keen to focus on the three people in the room, emphasising each individual’s sonic interpretation of the room’s acoustics. That’s how music should always be heard, he says, and Iris unpacks recorded sound to achieve that.

Jacobi was introduced to Rob Reng, an electronic music writer, professional scorer and one of the two engineers of Iris technology in 2016. Jacobi heard what Reng had achieved and instantly began building a business model, out of which Iris was born in 2018.

Now, here we are in a cool central London office, listening to one of only 30 numbered prototype pairs of Iris Flow headphones, which, at the time of writing, have achieved over £235k in backing – dwarfing the £50k goal of the Indiegogo launch campaign.

The pair we’re listening to is the culmination of countless adjustments. Iris’s commercial officer, Tom Darnell, demonstrates minute tweaks to the headband clamping force, weight calibration between the earcups, the strength of the magnets securing the earcups, and the level of cushioning. Even as we lower the optimal sample set onto our heads, Jacobi says, “I think there’s still an extra five to eight per cent we can get out of these, before we ship – before we’re truly happy."

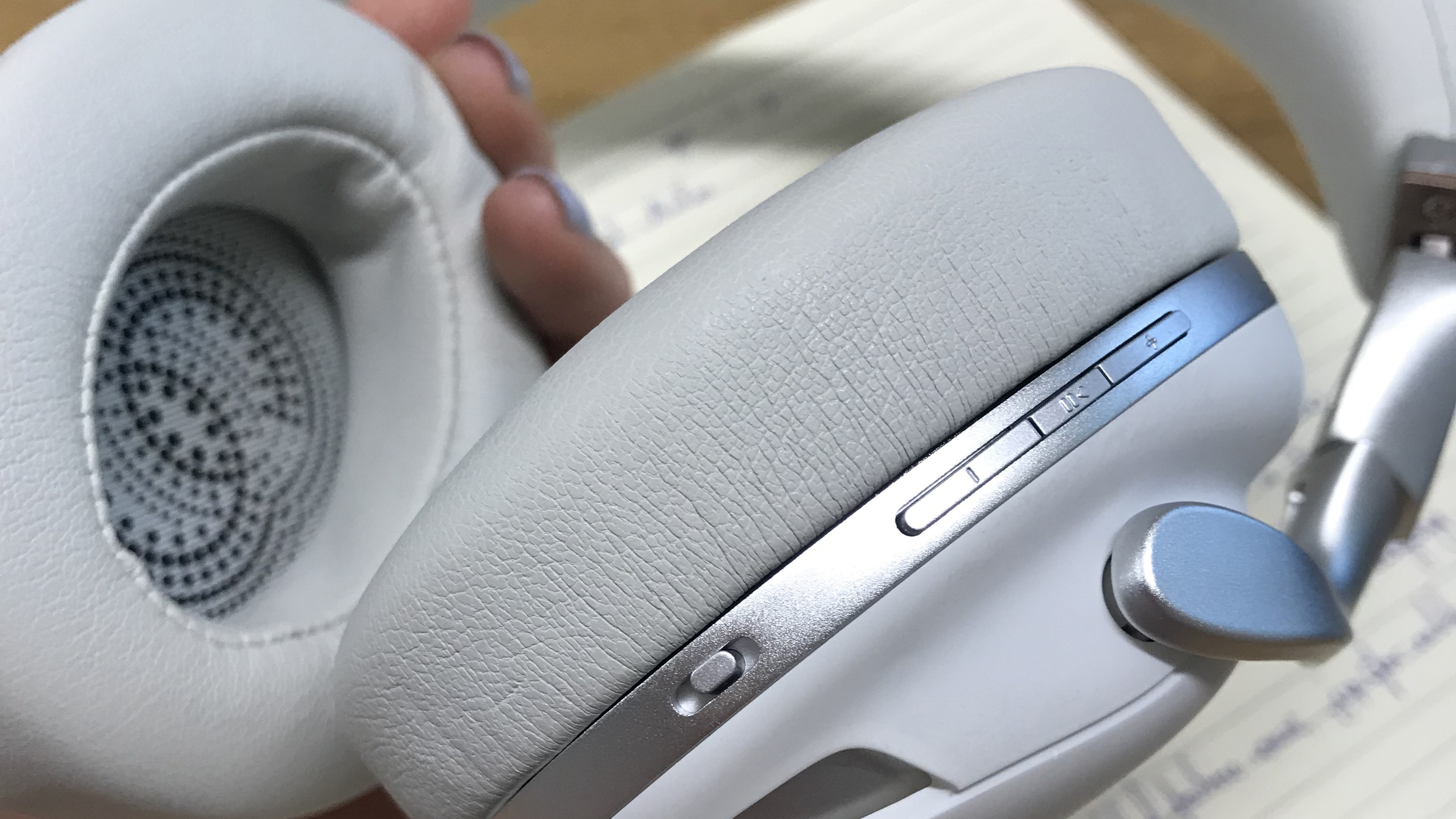

Are we, the listener, truly happy? Without toggling Iris on, there’s already plenty to like: the headphones comprise an aluminium chassis, 40mm beryllium drivers, a massive 37-hour battery life, Qualcomm cVc dual mics for call-handling (but not for noise-cancelling), aptX LL for low latency synchronised gaming and Bluetooth BLE 5.1 with support for aptX HD and AAC codecs.

The packaging is plastic-free and Iris is in the process of gaining Oceanic Global Standard certification: the recyclable cardboard box that the headphones ship in is the only one supplied, everything simply sits in the slimline, reinforced fabric travel case for the journey.

Of course, we’re eager to experience the USP. As we press the branding on the right earcup to initiate Iris, a light shining out from beneath the earcup shells makes both of them glow blue in the centre, as if imbued with the life force from James Cameron’s Avatar. There’s nothing verbal from the headphones to confirm that you’ve deployed Iris, but there doesn’t need to be – you can hear it.

Over the next 45 minutes or so, we toggle between Iris and non-Iris enhancement. At the start of Eh, Moskwa by Russian band Lyube, we deploy Iris and hear cable jangles as band members move. In Prince’s Purple Rain, we find ourselves fixating on the bowed strings through the verse, passages of reverb we’ve rarely noted and the yelps of the New Power Generation.

It’s as if these sonic nuances are jars on a shelf, and we’re able to pick each one up and scrutinise the label. In Michael Jackson’s Billie Jean, the shaker typically teasing our right ear isn’t where it normally is, a sensation that will doubtless upset some.

However, we’re revelling in the subtle key progressions, which present themselves distinctly and set apart from the bass that can often muddy the track through lesser headphones. The tap of the high hat in The Waterboys’ The Whole Of The Moon isn’t as forward as we remember it, but female backing vocals and other musical strands are suddenly opened out and unfurled.

The Light And The Glass by Coheed and Cambria now features the exhalation of Claudio Sanchez. We find ourselves digging out older favourites from our phone just to see what Iris does with them.

If Iris's dual-pronged approach – more realistic music and getting your 'Active Listening' 10,000 steps per day, albeit aurally – seems off-putting at first, we find ourselves 'walking' over to Coheed's bass player, as if at an intimate gig, even while considering it.

Will you love Iris? It certainly won't be for everyone, because even the most familiar of music tracks won’t ever sound the same again. But, of course, gaining a fresh new angle on old songs is precisely the reason why you just might come to love it.

Apparently, 75 to 80 per cent of blind testers in Iris’s market research preferred listening to Iris over non-Iris music. The ones that didn’t said that the presentation was “too immersive”. Perhaps the prevalence of flat, compressed or bass-bloated digital music that prevailed ever since Steve Jobs pulled 1000 songs out of his pocket on 23rd October 2001 has altered some tastes irrevocably.

But in a saturated market, the price of such a product is where the Iris Flows will sink or soar. At the indiegogo price of £269, the enviable sound tech (and that’s before we even get to Iris), class-leading battery life and high-end build are enough to justify the fee, whether or not you believe in the ethos.

With a regular retail price of £379 though, the headphones are devoid of features such as ANC, wearer-detection and app support for EQ alterations. Iris is against such things; despite the Iris Flow headphones containing the chipset and mics to support ANC, the company believes it isn't the healthiest way to listen.

To a degree, it’s a fair point. Artificial anti-phases that cancel out sounds our brain is tuned to notice (fuelled by our natural survival instincts) are not without fault. Nevertheless, customisable sound profiles have become desirable attributes on many a wishlist at this level. Is Iris engrossing enough to make consumers forego all of these, on something like the Sony WH-1000XM4, in favour of its expansive and thought-provoking listen? It’s a gamble – but for now, at least, it seems to have paid off.

Perhaps the ultimate beauty of Iris will be in its long-term goal of licensing its tech to others. When Amstrad was sold to BSkyB for £125m, Sky soon curtailed Alan Sugar’s telephony email devices to concentrate on the diamond in Amstrad’s arsenal: satellite receivers for its own Sky set-top boxes. So could the latest Hollywood blockbuster be shaped by Iris? Or Iris ListenWell feature in your next-gen gaming headset or as part of a game pass? Quite possibly.

As we leave the office, Jacobi recounts a recent argument over lunch with an audio exec in New York, who said that Iris simply wasn’t advisable – too hard a concept to sell. Jacobi left them with an early prototype of the headphones for a few days. That lunch companion is now actively drumming up commercial support for Iris.

We have also been given the chance to take the Iris Flow headphones away for 48 hours. As we step out into the muggy streets of London, the glowing cans are calling us back for more. Love or loathe the concept of Active Listening, we can’t help but echo the words of Roger Taylor when he told Iris, “You’ve got something here."

Becky has been a full-time staff writer at What Hi-Fi? since March 2019. Prior to gaining her MA in Journalism in 2018, she freelanced as an arts critic alongside a 20-year career as a professional dancer and aerialist – any love of dance is of course tethered to a love of music. Becky has previously contributed to Stuff, FourFourTwo, This is Cabaret and The Stage. When not writing, she dances, spins in the air, drinks coffee, watches football or surfs in Cornwall with her other half – a football writer whose talent knows no bounds.

-

lacuna I tried the app on my phone with spotify streams and I'm afraid I am not at all impressed. With algorithm turned on it sounds directly comparable with the normal spotify stream, however, turning it off makes the stream significantly worse than it would be in the spotify app. My inner cynic thinks the iris app artificially makes the spotify stream sound flatter to increase the apparent 'improvement' by the algorithm.Reply -

david.c Replylacuna said:I tried the app on my phone with spotify streams and I'm afraid I am not at all impressed. With algorithm turned on it sounds directly comparable with the normal spotify stream, however, turning it off makes the stream significantly worse than it would be in the spotify app. My inner cynic thinks the iris app artificially makes the spotify stream sound flatter to increase the apparent 'improvement' by the algorithm.

I disagree.

I was kind of suspicious of something like that also so compared the unaltered(no IRIS) sound using the app to the same songs on Apple Music. Personally I couldn't hear any difference and I did several comparisons. It would be unethical and too easy for people to discover them messing with the sound like that. Anyways I found the IRIS sound to be enjoyable and a definitely improved over the standard streaming quality. Enough that I went ahead and funded them through Indiegogo for a black pair. -

Jimboo Iris says its algorithm 'resynthesises lost audio information in a recording, allowing the brain to piece it back together'.Reply

Word salad at it's finest. -

david.c ReplyJimboo said:Iris says its algorithm 'resynthesises lost audio information in a recording, allowing the brain to piece it back together'.

Word salad at it's finest.

Maybe but did you read the article? It sounds reasonable and isn’t most important part in the actual listening? Personally I thought it sounded pretty damn good on my headphones with the sample song and a couple others I tried. But of course this kinds of things are extremely subjective and that’s why any headphone reviews are too be taken with a grain of salt. What sounds good to you might sound like crap to me and vice versa. -

Jimboo I don't know what you mean by reasonable? Heavy on the new technology phrasing and the obvious enthusiastic words of people heavily invested in their beliefs that they are onto something.Reply

It's all subjective , yes. -

MKF Interesting article about Iris algorithm and headphones (I have ordered one).Reply

I had hope that the technology behind the algorithm should have been uncovered even more. Testing myself with different recordings my guess is that information from both left and right channels are compared and the algorithm uses similarities and differences processing the sound. I have tested mono recordings, recordings done with one stereomicrophone only, binaural recordings, digitally remastered analog recordings and more. In some cases there is no difference in sound at all (I leave for you to test yourself), in other cases the sound is blured but in many cases (reflecting my CD archive) the "improvement" make listening much more enjoyable.

Regarding phase information and ambience nothing beats analog recordings or recordings made digitally with higher sample frequencies (4x) than what is used for standarad CDs/DVDs. But if your record archive is rather old, the IRIS algorithm is nice to switch on for some of the material (when you do not get disturbed by that the stereo image is slightly changed).

Hope that more sound compression formats will be supported in the future! -

jjbomber ReplyMKF said:Interesting article about Iris algorithm and headphones (I have ordered one).

I've been trying it on Spotify for a few days and I've been very impressed with it. All my Spotify listening will be done through the Iris app now.

One thing I don't understand. What is the difference in sending the signal through the app into existing headphones against using Iris headphones? I probably missed something in the write-up. Is there an advantage in sending it through both the app and again through the headphones? -

MKF Replyjjbomber said:I've been trying it on Spotify for a few days and I've been very impressed with it. All my Spotify listening will be done through the Iris app now.

One thing I don't understand. What is the difference in sending the signal through the app into existing headphones against using Iris headphones? I probably missed something in the write-up. Is there an advantage in sending it through both the app and again through the headphones?

As stated in the article Iris algorithm is run in the earphones, so you do not need to use the app.

I have not seen any tests between using the app or headphone. It should be intersting to know if there is any differences in sound. -

danmolecularimpact The key issue in the tech that Iris describes is the way our ears hear music bouncing around in live recordings--the way you hear and "feel" the room, as well as the stereo hearing effect that allows your brain to know where the piano is, where the drums are, etc. This is all very real, and it is lost by microphone placement in most recordings. How effectively the Iris technology is at using transforms to recreate your brain's ability to hear and feel "where" all the instruments are, remains to be seen. I have listened to the Spotify songs on my high end stereo system ( Big Magnepan speakers and mono block amps)....this is not the same as how Iris headphones will accomplish the sound, obviously, but it was intriguing enough that I might have to buy the Iris headphones just to really get the feel of whether this is a good thing or not :-)Reply