How the AirPods 3 were made – and how Apple plans to make them even better

We sat down with Gary Geaves, Apple's VP of Acoustics, to talk all things AirPods 3

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

While there's every chance that you're not familiar with Gary Geaves, millions of people across the world are familiar with his work. That's because he's the VP of Acoustics at Apple, and he leads the team that's largely responsible for all of Apple's audio products – and, for that matter, the audio components in products such as iPhones and iPads.

It's always a pleasure to speak to the fabulously enthusiastic Geaves, so I jumped at the opportunity to take a deep dive into the development of the AirPods 3 with him and Eric Treski from the Product Marketing Team.

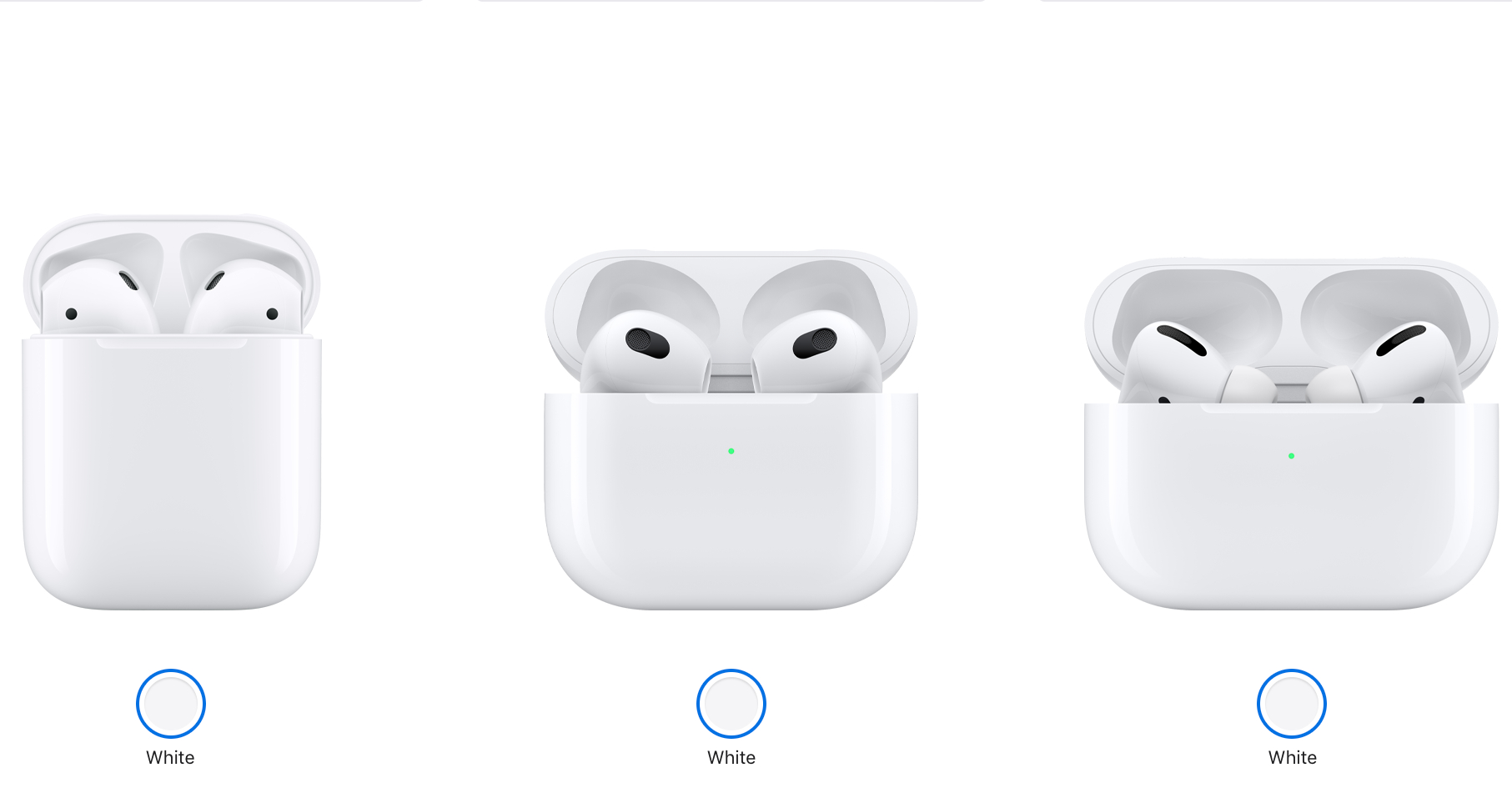

It quickly became clear that much of the work in designing the new AirPods 3 revolved around trying to solve problems inherent in the brief to come up with a true-wireless in-ear headphone that crams into its tiny form next-gen technology such as Spatial Audio and ups the sound quality ante without resorting to a burrowing or noise-isolating design.

As you'll discover from this long chat, Geaves and his team went to great lengths to overcome the obstacles presented, but there's one problem that still persists, and that we got to towards the end of our conversation. But first...

- AirPods Pro 2 vs AirPods 3: what are the differences?

Who is Gary Geaves?

It may be slightly surprising to learn that the man leading the team behind such a tiny, envelope-pushing device as the AirPods has a background in the British hi-fi industry, most notably at Bowers & WIlkins, but before that Geaves studied computational acoustics. He joined Apple about ten years ago to, as he puts it, “get more focus on audio”.

I’ve actually met Geaves before, when I was given the opportunity to tour his team’s labs in Cupertino right around the launch of the first (now sadly discontinued) HomePod in 2018. I got a clear sense of the obsessive nature of Apple’s Acoustics Team during that visit. It’s of course no surprise that Apple has loads of money to throw around, but the people I met and the facilities I saw suggested a serious appetite for acoustic problem-solving. That’s a very good thing considering the problems presented by the AirPods 3.

The challenges of non-burrowing earphones

Now I’m going to be upfront and say that I love an open, non-isolating headphone. There are plenty of scenarios that call for noise isolation and/or cancellation, most obviously those that involve planes, trains, buses, children or chit-chatting colleagues, but I do much of my listening while walking or jogging, and at those times I actually want some background noise to reach my ears.

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

The so-called 'Transparency' modes of the AirPods Pro and AirPods Max are very impressive (as are many similar features offered by rival noise-cancelling headphones) but they can never sound as natural as a true open design. What’s more, an in-ear headphone that sits outside the ear canal is always going to be more comfortable than one that’s wedged into it. Personally speaking, I'm therefore glad that Apple has stuck with the non-burrowing design for the AirPods 3, even though doing so presented lots of challenges for Geaves and his team.

“We started with looking very closely at the strengths of the original AirPods”, Geaves explains, “and we know many people really like the effortless open fit that doesn’t stick into your ear canal and rests comfortably on your ear. That doesn’t create a seal, which is what people like, but it creates challenges for the audio team”.

The biggest challenge, says Geaves, is that “no two ears are alike – each person’s are a unique fit, and what that means is the sound that people experience will be significantly different, especially the bass”.

This is where Adaptive EQ, which was first introduced with the AirPods Pro, comes in: “we’ve added an inward-facing microphone”, says Geaves, “which continuously monitors what’s being played by the speaker and tunes the bass and, to some extent, midrange frequencies as well, to deliver a really consistent frequency response regardless of the level of fit that each person gets”. The idea is that everyone hears the music the same way, and the way the artist intended.

The intersection between liberal arts and technology

That raises the question, of course, of how Apple gets to the point of thinking it knows what the artist intended. Geaves explains that the approach “is to really try and navigate the intersection between liberal arts and technology”.

The technology part “starts with a strong analytic foundation”, as he puts it. “Over the years we’ve conducted really extensive measurements and we’ve done deep statistical research in order to inform a kind of internal acoustic analytic target response, and we use that to design hardware around”.

One suspects that many companies would stop there, particularly as Apple’s data is likely to be far more advanced than that available to the average headphones manufacturer, but Apple is determined to not rely on analytics alone.

“We really understand that listening to music is an emotional experience which people connect with on a very deep level”, Geaves says, “so from the analytic tuning we work closely with an expert team of critical listeners and tuners. Many of these are folks from the pro audio industry, and really what they try to do is intentionally refine the sound signature for each product, AirPods in this case, so that it’s accurate, but it’s also exciting and moving”.

I imagine that someone with a background in computational acoustics, someone clearly so data-driven, would find it hard to hand a device built by science over to subjective human beings, but I get the sense that Geaves is genuinely appreciative of this part of the design process: “we respect music and the emotional impact that it can make and we want to deliver this natural experience”.

The added complications of Spatial Audio

The task of delivering the sound as intended apparently becomes much harder when a technology such as Spatial Audio is added into the mix, but Geaves explains that Apple leverages its position in the industry to get opinions from the people creating the music: “we have whole teams of people who deal with the kind of interaction between engineering and artistic folks – they don’t let me near artistic folks because I’m too much of a fan to be honest with you – but we do take feedback from people delivering the content”.

Eric Treski jumps in here to explain how “full circle” this process is, encompassing not only the Acoustics Team, but also the Apple Music Team and the team behind GarageBand and Logic, who have access to music producers and artists and from whom they take feedback.

But the differences between listeners are also even more of a factor with Spatial Audio than with stereo. “The shape of your ears, the width of your head, to some extent the placement of features on your face, the shape of your head even, mean that everybody hears sound differently”, says Geaves.

“These differences can be mathematically categorised by something that’s called head related transfer function. You’ll see this referred to as HRTF frequently. In developing this feature we captured thousands of HRTFs on different people. And these are quite complex, difficult measurements to do – we’re measuring the sound, the response or your ear to a speaker in multiple different directions – and we really did that so that we could come up with the best HRTF that works for everyone, which is again very easy to say and not easy to do. It’s not just creating an average, it’s creating the HRTF that’s kind of closest to everybody’s perceptual response”.

The approach taken to tuning Spatial Audio, specifically for music, is complex, too. As Geaves puts it, “it’s very easy to come up with a convincing demo that’s very whizzbang, but it’s not quite so easy to develop a feature that works across multiple people and multiple different products and multiple genres.

“We could really turn all of these nobs up to 11 and it would sound “oh, well that’s big” and then after about a minute you go “you know what, this is weird, I don’t like this”.

The aim is for Spatial Audio to sound natural and convincing, but that apparently isn’t straightforward. Given free, three-dimensional rein, “you have to take into account the position of your virtual speakers in space, so how far are they are from you, and the angle that they are in space, things like reverberation time – so you need to choose whether you want your thing to sound like a cathedral or a very small room with lots of carpet and curtains in and things like that. You need to think about decay times of the sound, channel gains and so on. And that’s a really artistic choice”.

Something I hadn’t realised is that Spatial Audio is tuned differently depending on the source device: “when watching a movie on Apple TV the virtual speakers are placed further away from you than when you’re watching on an iPhone”, Geaves says. Apparently, it would just sound weird to combine a fairly small screen that’s quite close to you with virtual speakers that seem a long way away.

The Bluetooth problem

The AirPods 3 were essentially built from the ground up, using custom-made components. “Nothing’s off the shelf”, as Geaves puts it. That includes the “very low distortion” loudspeaker, which is integrated into “quite a complicated acoustic system” that regulates the movement of the speaker, minimises pressure in the ear canal and features a “carefully tuned bass port”. The AirPods 3 also feature a “brand new, custom amplifier” that apparently combines high dynamic range with very low latency (which is particularly crucial for head-tracked Spatial Audio) and serious power-efficiency.

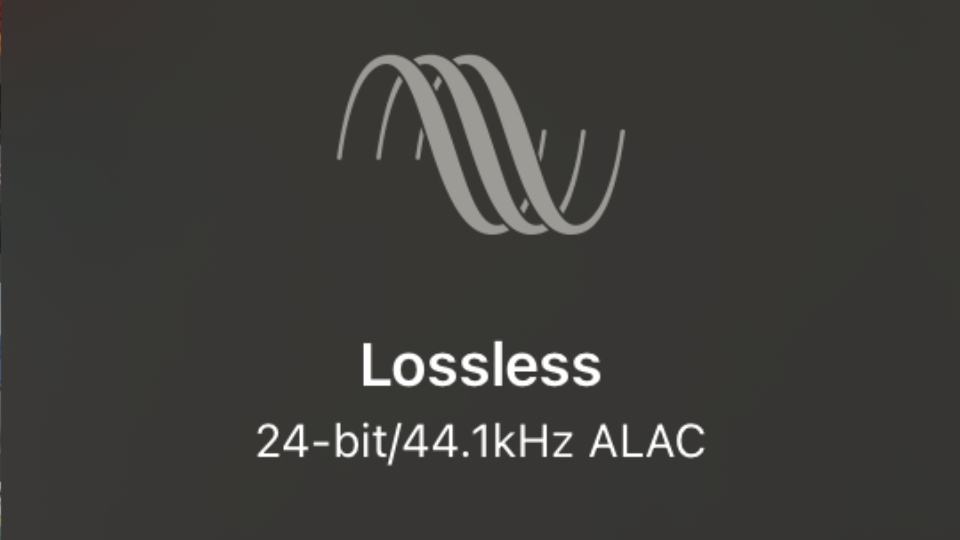

Everything points to Apple taking sound quality very seriously with the AirPods 3, and all of its modern-day audio products for that matter, and the recent launches of Lossless, Hi-Res Lossless and (in a slightly different way) Spatial Audio point to a real push towards higher audio quality. But there’s a catch, as far as I can see it – a bottle-neck that’s been preventing real qualitative leaps in the sound of wireless headphones essentially since wireless headphones came into being. I’m talking about Bluetooth, of course, which almost all wireless headphones, including AirPods, rely upon and which doesn’t have the data rate for hi-res or even lossless audio. I ask Geaves whether the use of Bluetooth is holding back his hardware and stifling sound quality.

“Obviously the wireless technology is critical for the content delivery that you talk about”, he says, “but also things like the amount of latency you get when you move your head, and if that’s too long, between you moving your head and the sound changing or remaining static, it will make you feel quite ill, so we have to concentrate very hard on squeezing the most that we can out of the Bluetooth technology, and there’s a number of tricks we can play to maximise or get around some of the limits of Bluetooth. But it’s fair to say that we would like more bandwidth and… I’ll stop right there. We would like more bandwidth”, he smiles.

Reading between the lines, I reckon Apple has a plan for overcoming Bluetooth’s current limitations. That could be as simple as switching to Qualcomm’s recently announced aptX Lossless format, but I wonder if Apple might have its own alternative to Bluetooth up its sleeve.

While it's clear that Geaves would love to go deeper into this topic right now, it's obvious that he's not allowed to do so. It seems that we'll just have to wait for the next generation of AirPods to find out whether he and his team have managed to solve the Bluetooth problem and develop a pair of genuinely hi-res wireless headphones.

MORE:

Our verdict: Apple AirPods 3 review

How HomePod was made: a tale of obsession from inside Apple’s audio labs

Here's our list of the best wireless headphones you can buy

Tom Parsons has been writing about TV, AV and hi-fi products (not to mention plenty of other 'gadgets' and even cars) for over 15 years. He began his career as What Hi-Fi?'s Staff Writer and is now the TV and AV Editor. In between, he worked as Reviews Editor and then Deputy Editor at Stuff, and over the years has had his work featured in publications such as T3, The Telegraph and Louder. He's also appeared on BBC News, BBC World Service, BBC Radio 4 and Sky Swipe. In his spare time Tom is a runner and gamer.