How your wireless earbuds are made: creepy dummies, AI and sonic torture chambers

It's easy to make a pair of earbuds... right?

It would be easy to underestimate the impression Jabra has left on the world of audio and telecommunications. Initially founded in America in 1983 and later acquired by Denmark's Great Northern Telegraph Company (responsible for some of the first telegram lines to cross from Europe to places such as China and Russia), the brand boasts 44 million users worldwide of everything from headsets to hearing aids.

Our focus, naturally, is on Jabra's ever-burgeoning line of wireless earbuds and occasionally its over-ear headphones, but it's worth appreciating that the Danish brand pumps out video conferencing systems, smart speakerphones, office communication solutions, office cameras, hands-free headsets and, of course, hearing aids. Jabra is all about communication, something that goes way beyond hooking you up with a new pair of running buds for a handful of notes.

Satisfying such an impressively diverse consumer base on such a global scale is clearly a pretty big deal, then. When you're shipping headsets from Seoul to São Paulo, you need to be pretty confident that you're sending out the finished article. We took a trip to Jabra's headquarters just outside Copenhagen to see for ourselves, from design and research to testing and conception, just what it takes to get a pair of earbuds (and much else besides) from the lab and, one day, into your ears.

A design for life

For Jabra, nothing gets made without a clear concept of what the end-user requires. According to Iain Pottie, Jabra's head of design, the brand's design philosophy is led by its end-use case, starting with the question of how any items will be used by its ultimate consumer.

It's something that Iain views as a genuine responsibility. He speaks of a "position of privilege" in that Jabra products often end up in a unique and intimate place on a customer's body (in their ears, mainly), and that brings with it the necessity of ensuring that such products meld functionality with comfort and discretion.

Iain describes Jabra's products as "a manifestation of the brand", speaking of the company's eventual solutions as being a reflection of a set of design values.

"We have a set of principles that we're working with. We have a narrative of being planet-centric. These principles are going to guide us and they're the ways that we actually help the company make decisions about whatever the right things to do are," he tells us.

Get the What Hi-Fi? Newsletter

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

This feeds into how Jabra's design division interacts with its engineering teams. Iain is interested in getting his team to think about the key functions and purposes of Jabra products for the end-user, rather than allowing aspects such as comfort or even sonic performance to become secondary to lesser considerations.

This means a dialogue between designers and engineers rather than having a strictly defined end goal. As Iain explains, a designer isn't "somebody who turns up at the beginning of the process and says, 'Here's a wonderfully aspirational dream.' You have high levels of interaction between designers and product management and, ultimately, our users". By figuring out what users want, Jabra employs a flexible yet focused process with the customer at its core.

The inevitable AI interlude

No, not even here can you escape the inevitable mention of those two letters that many of us now quiver at the sound of. Artificial intelligence has been around for a lot longer than the two or so years in which it's actually been at the centre of the public consciousness, though there's little doubt just how transformative most tech companies believe AI, in all of its guises, will be in the coming years.

Jabra is no different. While much of the brand's integration of AI, particularly machine learning, is going to be focused on communication-based products such as conference speakers and office aids, very few technologies are prone to stay in their given lane once a utility is discovered; noise-cancelling tech was pioneered to aid clearer communication for pilots, after all.

Aside from providing a go-between for audiologists and their patients by compiling and summarising essential data, Jabra envisions AI becoming far more integrated into the world of wearable tech and audio. If you're working in the service industry, for instance, an AI-boosted earbud connected to the cloud can now access tasks and information from a central database and assign them to you on the go without the need for a manager or colleague to assign you your next tasks.

Smart speakers and conferencing tools can also be improved by emerging technologies. Vocal recognition algorithms which learn the voice patterns of various meeting attendees can give more seamless interactions across virtual conferences, something that can then be implemented into smart speakers so that the tone and nuance of commands are more readily understood. One of the gripes users often have with smart speakers is that they can often need commands to be rather literally spelled out, something that AI and machine learning could soon help rectify.

This of course is something that many audio brands are looking to integrate into their respective products and technologies, with many recent or upcoming debutantes proudly boasting of AI-boosted algorithms for enhancing voice calls, boosting noise-cancelling capabilities or even integrating chatbots and virtual assistants (think ChatGPT) into compatible headphones and devices. What a disturbing place the future is...

Jabs' fab labs

Design and imagination are nothing without research, development and testing, and it's in these areas where you get a sense of Jabra's pedigree. Leaving the company's pod-like meeting rooms, we're guided back to the facility's beating heart: the Jabra labs. If you ever thought that tech companies spend most of their time playing table tennis and occasionally scribbling an idea for a new speaker on the back of an old napkin, it might be time to book yourself a flight to Copenhagen.

The Jabra testing facilities are deeply involved and undeniably impressive. Stretching back far further than you might initially realise upon first arrival, the laboratories are subdivided into various internal pods, chambers and structures, many of which are raised on platforms or isolated entirely from the rest of the facility. Covering every single area takes a good hour at least, and that includes skipping over some of the smaller or less accessible areas altogether.

What's clear, though, is that making a pair of headphones, earbuds or speakers involves a wide variety of parameters which testers seek to control and/or account for as they go about their rigorous procedures. "Test, test, test, learn, learn, learn" is inscribed on Jabra's official website, and having seen the company's facilities and the processes behind them, that's more than an empty mantra.

There is, in short, a designated area or room for almost every aspect of audio design and development. The first room we enter is an acoustic anechoic chamber designed to absorb all sound waves, creating more optimal conditions for testing sonic directionality. This rather eerie experience feels disconcerting in its echo-free nature. By eliminating as much external noise as possible, testers can pinpoint more accurately any given source, drilling down into the sonic characteristics they want to hear and alter rather than having results corrupted by unwanted reverberations or distortions.

Noise cancelling, too, requires its own space, here known as a "Diffuse Field chamber", an unpadded room sporting a creepy single dummy placed in the centre that puts one in mind of a torture scene from a novel about Soviet gulags. This particular space sports hard, reflective surfaces, none of which run parallel to one another alongside various uncorrelated sound sources (eight generators and eight speakers). That creepy dummy, known officially as a "HATS" (Head And Torso Simulator) has its own artificial ears which listen to the surrounding diffuse noise in the chamber; by comparing the measurement of the room's noise with the HATS dummy with and without a headset on, testers can get a true sense of the ANC's overall performance.

This is just the tip of the iceberg. Another chamber entirely blocks out radio signals in order to test antenna performance, while a sort of mini wind tunnel demonstrates how Jabra strives to optimise microphone performance in blustery or adverse weather conditions. There's even an old car (a Hyundai) for assessing how well voices and sounds come across in a typical utility space, though we weren't treated to an indoor test drive. Probably for the best.

A fitting finale

What strikes you when touring a lab such as Jabra's is just how profoundly so many varying external factors can affect the process of putting a product together and, as a consequence, the lengths that manufacturers are forced to go to in order to gain some degree of control over the varying processes involved. The last two rooms on the tour are perhaps the finest examples of this, and while it's an undeniable cliche, Jabra really did save the best until last.

The first of our final treats came in the form of the so-called "Flexible Acoustics" room, an unassuming space about the size and dimensions of a small squash court, an impression aided by the light wooden flooring and white painted walls. What squash courts don't have, however, is manually controllable acoustics. At the touch of a button, the curtains surrounding the walls move across while mechanised shutters lock into place, utterly changing the room's sonic characteristics from a sonorous chamber to a flat, echo-resistant sonic wasteland.

By opening or shutting the panels, the acoustic absorption changes, so when the panel is shut, sound waves are deflected and the room has a "long reverberation time". Once opened, sound waves will be absorbed and the room's reverberation time becomes shorter. The experience is mesmerising, highlighting just how profoundly the acoustic characteristics of a building can affect a sound played within and, perhaps more importantly, how little attention we pay to such effects.

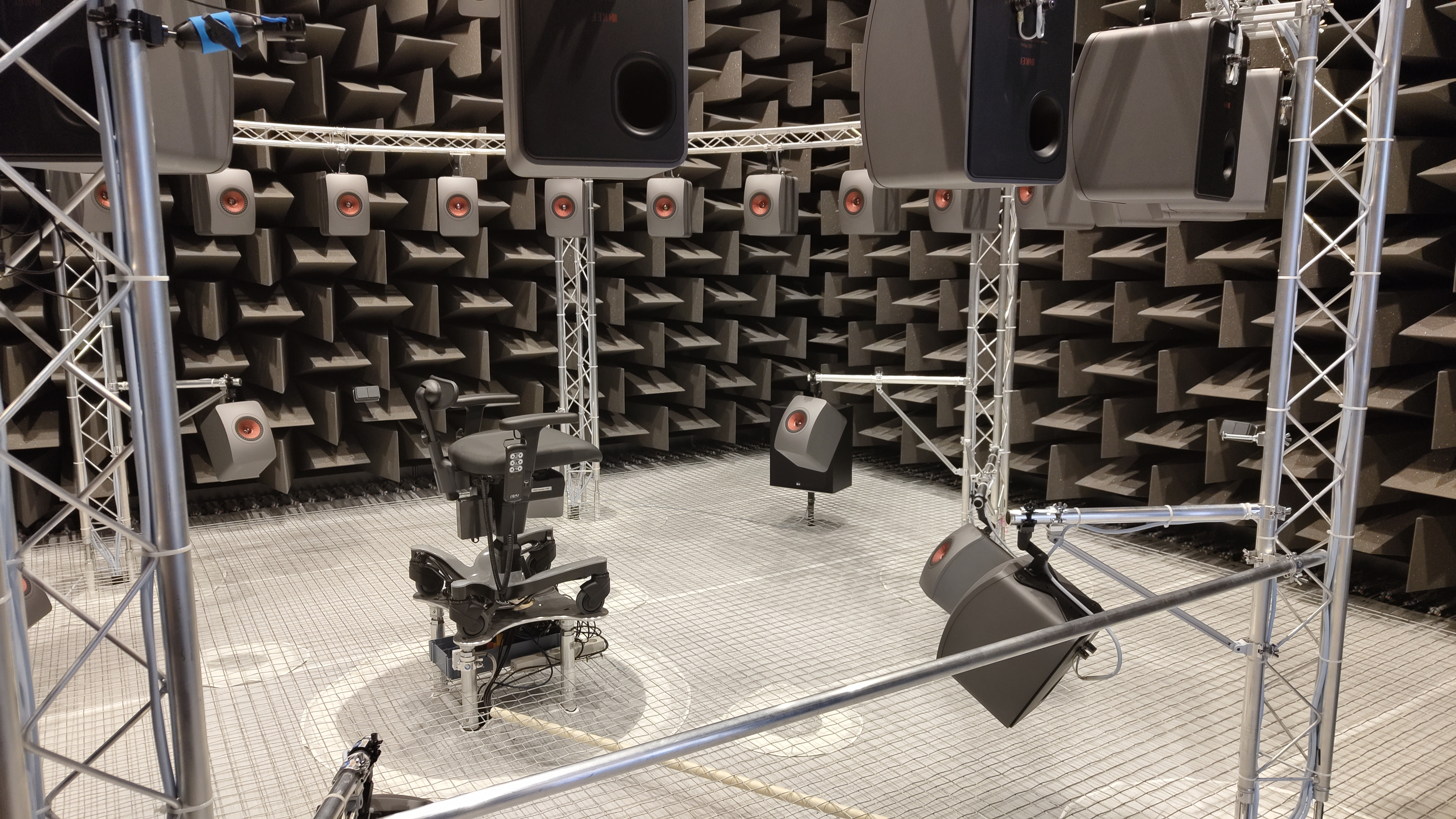

The second was pure indulgence for hi-fi fans. As shown by the photos, this final chamber was dedicated to assessing sonic directionality and surround sound, with dozens of KEF LS50 Meta speakers mounted all around the circumference of the oval space and a single chair placed in the middle. Bringing to mind a scene from A Clockwork Orange, the experience of hearing a raft of KEFs firing audio that swirls above, behind and around your head as you balance on a floor made of industrial-strength wires (see picture at top) is not a treat enjoyed by many.

A humbling experience

Aside from the joy derived from having more than a dozen KEFs firing into your brain or the pleasure of sampling the delights of Danish cuisine (not at the labs themselves), there's real value in taking a tour of any design facility or manufacturing plant, be it from the point of view of a consumer or, in my case, as a consumer-cum-journalist. Just as it's become so easy to view the food piled on your plate or squeezed into on-the-go packaging cartons as an end result without an initial cause or process, it's become second nature to view consumer electronics as a sort of God-given inevitability. Headphones are the way they are because, well, that's the way they are, and that's all that need concern us when we pop them into or over our ears.

The final result, however, is merely a single link in a very long chain, one that most of us rarely imagine and very rarely appreciate. The process involved in constructing what seems like the simplest of products is time-consuming and resource-heavy, the result of labour, innovation and profound levels of expertise. I'd only spent a single day at the Jabra labs, knowing full well that this incredibly involved process from conception through design and then research and development was essentially just a peek behind the proverbial curtain.

If that doesn't convince you to take a little more care with your battered old earbuds the next time you're off for a run, the effect on an audio reviewer/journalist certainly is a humbling one. While it won't be enough to affect our rigorous and much-envied testing procedures, it's always good to note, even in the depths of frustration and/or ire with a given product, the time and effort that actually went into making it. Very few companies ever make "bad" products, and if the passion and dedication of Jabra's employees or the comprehensiveness of its facilities are anything to go by, the vast majority of brands are striving to make their products the best that they can be.

MORE:

Read our Jabra Elite 10 review

Inside the Sennheiser factory: assembling audiophile headphones and listening to £60k electrostatics

I spent the evening at KEF’s new Music Gallery and it was hi-fi and home cinema heaven

Harry McKerrell is a senior staff writer at What Hi-Fi?. During his time at the publication, he has written countless news stories alongside features, advice and reviews of products ranging from floorstanding speakers and music streamers to over-ear headphones, wireless earbuds and portable DACs. He has covered launches from hi-fi and consumer tech brands, and major industry events including IFA, High End Munich and, of course, the Bristol Hi-Fi Show. When not at work he can be found playing hockey, practising the piano or trying to pet strangers' dogs.