I experienced the world's first "interactive 3D symphony" in a new audio format that expands on the ideas of Dolby Atmos – here's how

“Welcome to the first-ever interactive 3D symphony!”, said the blurb on a press release for a new recording by Brian Baumbusch. Well that sounds exciting, and is clearly just the sort of thing I should be investigating, as Mr Baumbusch suggested in a note to me. He had read my previous enthusiasm for other immersive music, and suggested that I might enjoy this new album of his, called ‘Polytempo Music’.

“You’ll witness an orchestra of music as a 3D entity that will be remixed as you move around it and as it moves around you in a through-composed choreography of sound,” he wrote to me. But then, more worryingly he added – “To achieve this, I’ve developed a method that I call ‘spatial audio animation’ for which I hold a provisional patent.”

Oh here we go. So was this a nutter email? I do get these regularly; someone has invented a whole new speaker concept, or a hitherto unknown amp circuit, or a cosmic bowl you can put on a shelf to go ‘bong’ and your hi-fi instantly sounds better. I considered diving for cover.

But Mr Baumbusch doesn’t google as a nutter. He’s a youthful but longstanding composer and musician who formerly specialised in the music of central Argentina, then of Bali – the latter rather enthused me, as who among us hasn’t wondered what the heck is going on behind the clearly complex but impossible-to-appreciate bowl-ringing racket made by Balinese gamelan orchestras? More than a decade ago, Baumbusch even started making his own new instruments inspired by the mysteries of gamelan, and he founded ‘The Lightbulb Ensemble’ to play them. He has lectured, had commissions for all sorts of august bodies… in fact he has one of those CVs that makes you feel rather inadequate about your own.

And crucially he is not only a composer but also an animator and a software developer. So perhaps he is indeed uniquely placed to deliver something which is described in the app blurb as “music as a 3D entity that moves around you…” and which invites you to “choose your path around an orchestral galaxy of musical streams and marvel at the once invisible waves of music as they pulsate around you like a flock of starlings painting patterns in the sky.”

Let’s just repeat that: we are to expect once-invisible waves of music pulsating around us like a flock of starlings painting patterns in the sky. You don’t hear that sort of stuff from Dolby, do you!

Wot, no Atmos?

Talking of Dolby, yes, why is he going for something entirely new in terms of an audio format? Why not just deliver it in Atmos, given that has become the default method for immersive audio via real multichannel systems and even via stereo headphones? Why is he reinventing the hemisphere?

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

In fact, there is an Atmos release of Baumbusch’s new recording available, if that’s what you want. But he pointed out in our correspondence that, even with head-tracking headphones, the Dolby Atmos mix would offer three degrees of listening freedom – yaw, pitch, and roll. His interactive app version offers six: the yaw, pitch and roll of headtracking, as well as the ability to navigate through the sound environment in all three dimensions.

I could add another reason for moving beyond Dolby Atmos: Atmos on headphones just doesn’t achieve any true sense of surround, does it? Not only are Atmos music streams wildly compressed in data terms (closer to MP3 than they are to lossless), they don’t really put music all around you, let alone above you – or they don’t for me, anyway. I usually keep my very-much-loved Apple AirPod Max headphones switched to lossless stereo, not the Dolby Atmos which Apple has so successfully championed (and I reckon any one would pick the same preference given some blind A-B between the two formats).

I shouldn’t single out Dolby Atmos for dubious success in this regard. I have never yet heard sounds “coming from all around me” from any headphone, any format – even some headphones I have tried which had extra drivers positioned at the back; even a pair I did decades ago which required additional cables from an AV receiver or sound card carrying discrete rear-channel information – ridiculously hard to use, yet no real rear delivery from any of them.

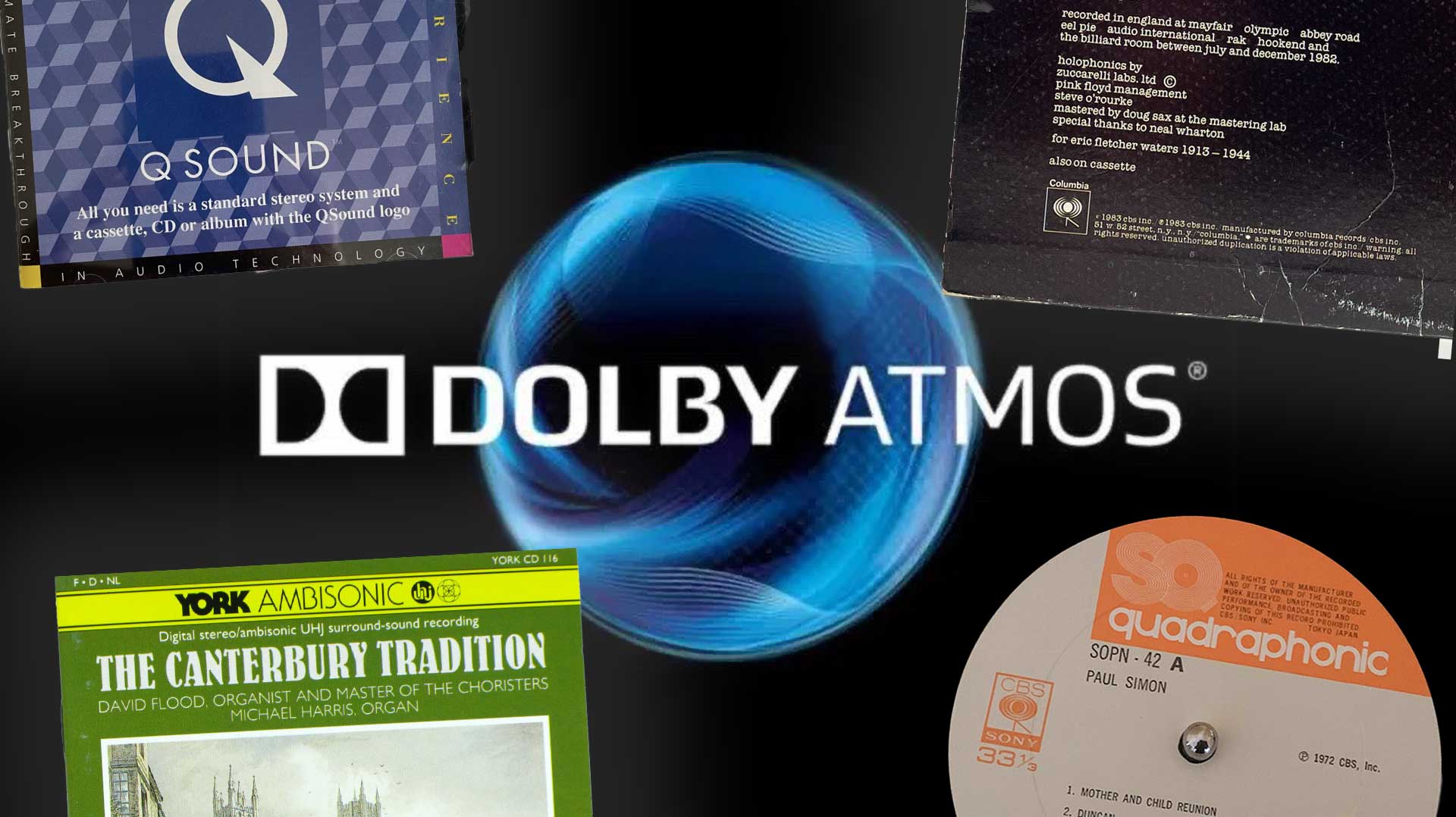

Nor much from any of the magical stereo-mix methods that have come and gone over the years, whether Holophonics on Floyd’s ‘The Final Cut’, QSound on Madonna and Roger, not Ambisonics or Sony 360 or any of that. That’s why I have a physical 5.1.2 Atmos speaker system at home for all the 5.1-channel and Atmos music available – precisely so that I don’t have to pretend it can be done by headphones.

Oh, one exception. Some years back I heard a binaural horror recording by university students on YouTube which really did put things behind me, though it did so for nearly the whole mix, rather than creating a real ball of sound. The surround felt like it was separated off by a kind of wall across the headspace from left to right, with everything pushed behind it; this I interpret as an applied HRTF (head-related transfer function), which is, in the simplistic terms I generally understand, roughly what the backs of your ears and the rest of your head do to any sound that comes from behind you. So a suitable (ideally personalised) HRTF may fool you into thinking sound is behind you, as used in binaural recordings and in other VR/AR tomfoolery. (Rather dimly I didn’t bookmark that YouTube video which was so effective, but it might have been this one, made in binaural by Birmingham University students: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y_sSQ4d9ohk.)

But music is more complex, and rather harder than speech and effects to effectively position using positional cues. So can Brian Baumbusch’s app do it?

Polytempo Music

Polytempo Music is an album in 12 parts, which you can buy as an app. Mr Baumbusch originally offered to ship me a Meta Quest 3 VR headset on which to experience his immersive VR version, but this fell down rapidly when he realised I was in Australia, not the USA.

Happily it’s also available as an interactive mobile app for iOS and Android; the iOS version costs £7.99 in the UK, $14.99 in Australia, and it can be played on any conventional headphones – presumably, for preference, on high-quality headphones. And I can’t help thinking that a good pair of over-ears will be doing a better job than what you’d hear from a Meta Quest headset – either from spaced speakers around the goggles (no bass) or Bluetoothing to what must necessarily be earbuds. Whereas I could plump for the large Apple AirPod Maxes, purpose built for so-called immersive performance, also a high global headphone reference which Mr Baumbusch must surely have considered, and most likely directly tested with his system.

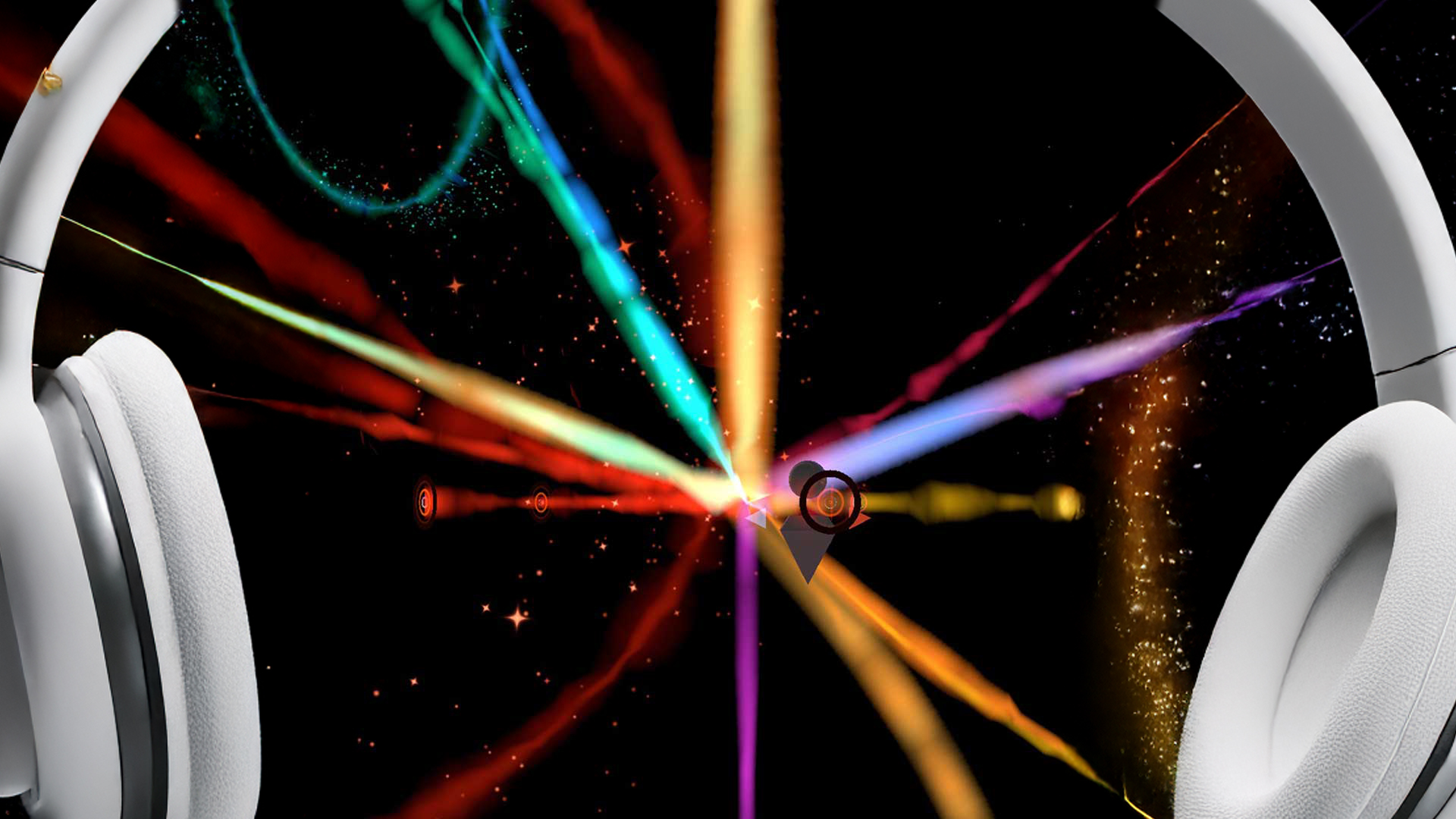

Start up the app and the album just starts playing, while making pretty coloured sparkles and swirls in the middle of the screen.

Just to cover off the music: this ain’t rock-n-roll. But I thoroughly enjoyed what it is. Performed by the San Francisco Contemporary Music Players, ‘Polytempo Music’ features an orchestra with clarinets, oboe, violins, viola, cello, double bass, piano, vibraphone, harp and guitar. The compositions are certainly not gamelan-atonal, nor particularly abstract: it is complex, but has signposts to follow, with tonal shifts and arpeggios within which anyone attuned to extended Glass, Reich and Richter pieces will feel perfectly at home.

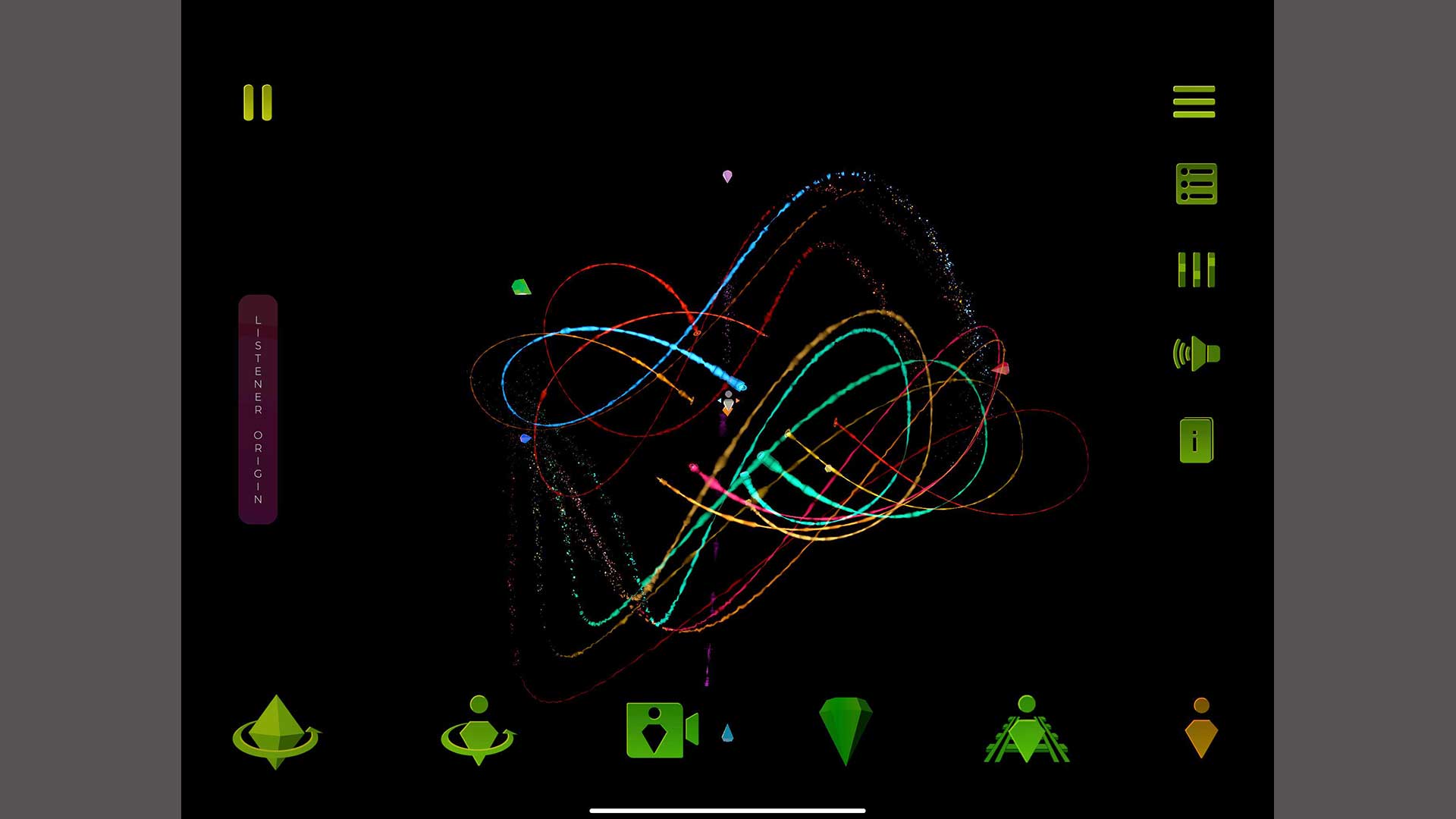

Leave the album playing, and you soon realise that the colours sweeping around the screen are a series of plots for the individual instruments, showing how they have been mixed within a 360-degree sound stage. And boy have they been mixed. By track III, Murmuration of Twelve (those starlings again), the multicoloured traces are rotating around the headspace in twinkly abandon; it’s very pretty just on a tablet, and must be mesmerising to watch inside a VR helmet.

As for the positioning of music when being panned to these positions, the front soundstage is very effective, while the rear positions were more illusory: for my ears they tended to not quite get right behind, more handing over from extreme right to extreme left, say, or existing behind the same kind of virtual-wall effect that I had experienced with the binaural horror recording.

The positioning is more effective if you actually watch the coloured swirls while listening. I’m guessing this is some power of suggestion, or of combining multiple senses, so that if we also see where the sound is going, we’ll accord it more positional belief than by merely hearing it.

Is it also a benefit to keep everything moving in this way, rather than creating a more fixed mix of instruments in a true 3D soundstage? There are some tracks on the album which are more static than others, but on the whole, things do keep moving all the time. If this is to be an ongoing ‘format’ for more recordings, it would need to work equally well with more statically positioned mixes.

I asked Mr Baumbusch about this, and he sent a demonstration of more-static music which he has made under the auspices of Holography Records, the label he has created with a mission of presenting interactive cross-genre music releases. A Debussy excerpt shows how the system might be almost as interesting with more classically positioned recordings, but with the listener able to move (and fly!) around the stage.

A journey into sound

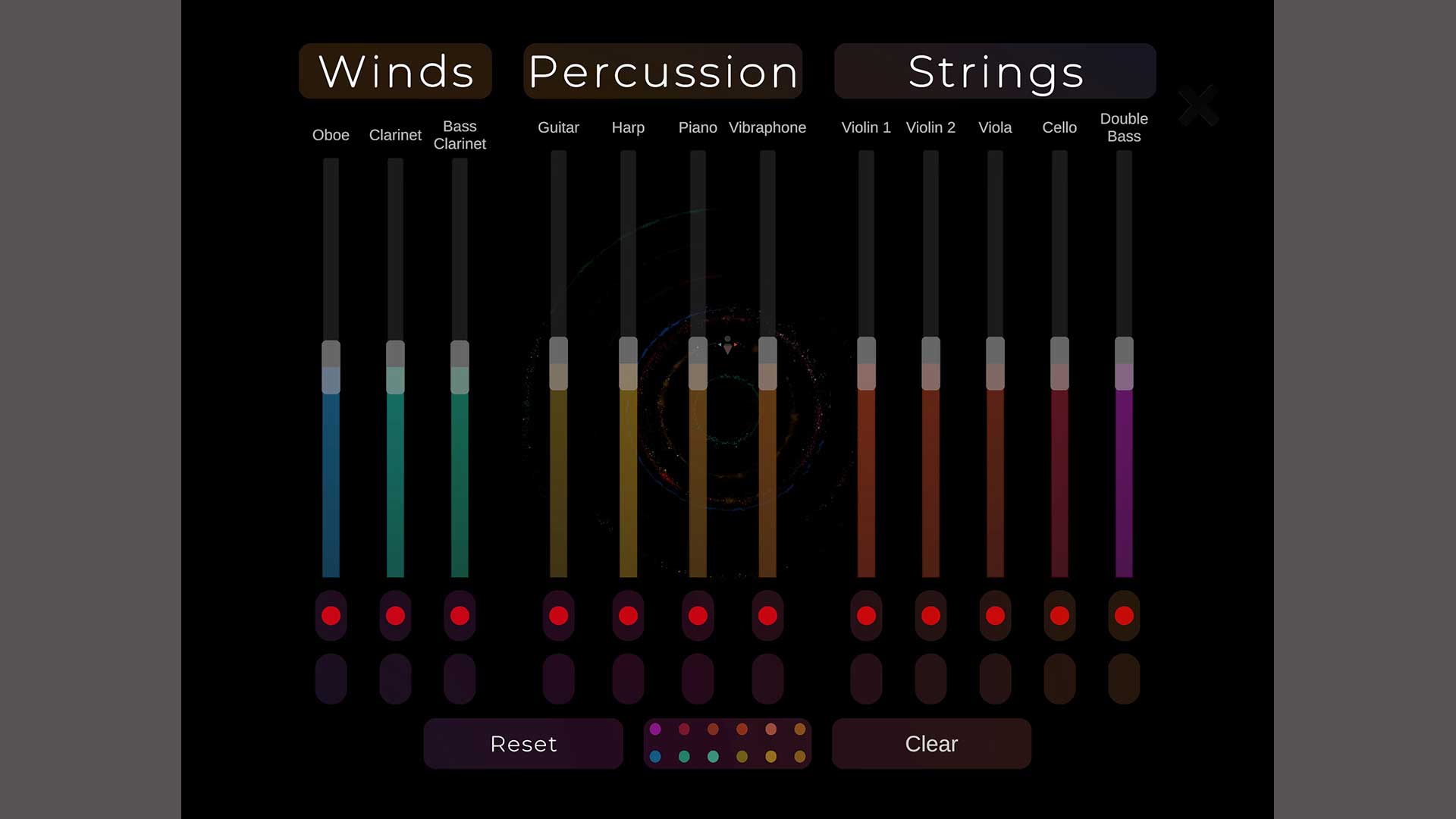

Watching the swirly stuff is just the beginning. While you can’t stop the mix swirling around in the predetermined way Baumbusch has designed it, you can vary each instrument’s individual level via coloured sliders that match the instruments, so creating your own mix.

But the real trick is to grab the little avatar which represents your listening position and then move it through the swirling instrumentation, or spin it around, or even send it on a journey of movement in counterpoint to the swirling instruments.

This is quite the buzz: it feels like a real journey into sound. As you approach instruments, they become louder, and their movements change perspective as you move around or spin. This happens with no notable latency, even when listening via Bluetooth, so it feels entirely fluid and natural. On one track, Pas De Deux, instruments are separated into a top ‘stage’, a mid-level stage, and a bottom stage, with the upper instruments playing at a faster tempo, the bottom ones at a slower tempo. As you move your avatar between them, your perception of the music changes significantly; your movement really does become part of the performance, or at least of the 3D mixing.

And again, the addition of the tactile and visual interaction seemed to improve my acceptance of a genuine 3D environment. Humans favour visual stimuli, after all, so perhaps the visual element takes some level of critical attention away from the ears, aiding the immersion. There’s also some overall reverberation added, notable when you pause the music suddenly and hear it tail off as if in a fairly large cathedral.

How exactly does it all work? Mr Baumbusch informs me that he uses the Unity Real-Time Development Platform, and that for most of the album there are 12 spatial audio ‘object’ channels, or mono ‘audio sources’, one for each instrument (in some sections the piano left and right hands are split into separate objects). These move around the stage with their audio signal delivered to the listener based on a manually set distance attenuation curve that the listener can define using the "audio spatialization" slider; the listener can also enact individual volume adjustment on each channel as well as activate/deactivate the audio sources at will.

Although originally recorded at 24-bit/96kHz, each stem is mixed down to 16-bit/44.1kHz and will ultimately be rendered to the listener lossily, he confirms – this would clearly have to be the case if listening via Bluetooth. It emerges in what is a binaural mix and so yes, incorporating HRTFs for rear positions.

For future releases, depending on the total number of channels, he says they are considering different types of audio delivery formats at higher fidelity.

Format for the future?

So I must declare this a success, for this album at least. Waves of music pulsating like a flock of starlings painting patterns in the sky? I’d have to say that box was definitely ticked during my listening experience with ‘Polytempo Music’.

Is it a format for the future? After all, there have been previous attempts at some parts of this: Björk’s ‘Biophilia’ came out as an app you could use to reconfigure the music; Nine Inch Nails, Radiohead and Linkin Park have all issued multitrack stems that allow you to change levels and so remix songs; artists such as Peter Gabriel and The Flaming Lips have tried multiple ways to make their music interactive and user-controlled. None of these ever yielded a format that came to stay.

Mr Baumbusch is already approaching other artists with a view to releasing recordings on his Holography Records label, either individually or via a combined record company app which would operate similarly to the Polytempo Music app.

Meanwhile, of course the rise of VR and AR does provide an environment in which new ways of doing things are required. A system that ties VR visuals to an impressively effective immersive audio environment might be just what some of the companies pouring billions into their goggles are needing right now. Mr Baumbusch should perhaps be hurrying to finalise that provisional patent of his.

MORE:

These are the best wireless headphones we've tested

We rate the best stereo amps

Our picks of the best bookshelf speakers

Jez is the Editor of Sound+Image magazine, having inhabited that role since 2006, more or less a lustrum after departing his UK homeland to adopt an additional nationality under the more favourable climes and skies of Australia. Prior to his desertion he was Editor of the UK's Stuff magazine, and before that Editor of What Hi-Fi? magazine, and before that of the erstwhile Audiophile magazine and of Electronics Today International. He makes music as well as enjoying it, is alarmingly wedded to the notion that Led Zeppelin remains the highest point of rock'n'roll yet attained, though remains willing to assess modern pretenders. He lives in a modest shack on Sydney's Northern Beaches with his Canadian wife Deanna, a rescue greyhound called Jewels, and an assortment of changing wildlife under care. If you're seeking his articles by clicking this profile, you'll see far more of them by switching to the Australian version of WHF.