Home viewing has taken over, but cinema still lives, and I do like seeing epics on a commercial big screen with a room full of people, though sometimes these days it turns out to be almost a private showing in a near-empty auditorium.

For best results I choose particular cinemas and even specific screens: Elvis and Oppenheimer at Sydney’s Cremorne Orpheum Cinema 4 were particularly powerful experiences (they run that room loud!), and you get a bonus Wurlitzer coming through the floor on Saturday afternoons, something you rarely get at home.

During Sydney’s 2024 Vivid Festival, when the city illuminates itself dramatically to celebrate all the energy it saved during Earth Hour, I went to an unusual film screening at the Opera House. It was unusual because the film would be shown only once, and would never be shown anywhere ever again in that form, and you had to be there to watch it – and so did the director, Gary Hustwit.

This film is a documentary about Brian Eno. It’s hard to say that I fully love Brian Eno, because there are many Brian Enos, and I’m not sure I like all of them, but some of them I do, very much indeed. I am particularly indebted to Discreet Music, a whole side of vinyl where Eno makes soft ‘bong’ sounds on generative loops that go round and round and fade up and down; nothing much happens for 20 minutes and it eventually fades away. (I like to think it actually went on for days at the time of conception, but such extended Max-Richterian flights of fancy were sadly limited by the vinyl format back in 1975.)

In my youth I would play Discreet Music over and over during dreaded university ‘revision’ periods, because it masked all the noises of the world with a relaxing and undistracting blanket of bongs. So ingrained is Discreet Music for me that these days I hardly need play it at all; I can summon it in my head at will, bringing an instant combination of calm and nostalgia. Music listening, or even musical thought, is marvellous for mindfulness, as many of our hi-fi-loving readers will know.

Audio bongs to generative video

So for his Eno documentary, director Gary Hustwit first amassed hundreds of hours of footage and interviews with or about Eno. But instead of then hunching down in a mixing suite to create a linear edit of his film, Hustwit followed Eno’s own ideas and set about designing a system that could create a video documentary in a similar way to how Eno made his blanket of audio bongs. During each showing, Hustwit sits at the side of the stage overseeing his console-topped automatic editing machine, which cuts the extended video archive together in real-time and in unique ways, so that every showing is indeed unique.

I can’t tell you how unique exactly, because I only went once. But I’m pleased to hear that Hustwit will host a 24-hour online event (paid entry) on 24th January that will include the streaming of several different versions of the Eno doco, thereby making a direct comparison possible.

Get the What Hi-Fi? Newsletter

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

His machine uses technology from (or called) Anamorph, co-created with digital artist Brendan Dawes, who has previously wowed the world with such things as ‘algorithmic sculptures born from the Apollo 11 moon landing transcript’, and ‘physical sculptures created from Barcelona airport passenger numbers during COVID’.

I think I prefer the Anamorph concept, which Dawes and Hustwit first used in 2023 to create a 168-hour-long film based on Eno works for the Venice Biennale, before debuting the Eno documentary in 2024.,

You might be wondering whether a documentary edited on the fly by a computer would yield a disconnected collection of nonsense. As I understand it, there’s no great AI overseeing decisions in Hustwit’s machine: more a group of parameters which he sets in motion and then merely monitors for problems. So can it weave a narrative and tell the story properly? If vital parts of Eno’s career are simply randomly omitted each time, is the documentary really complete? Might we get a similar experience simply by rabbit-holing Eno on YouTube?

Well, my experience of the Eno documentary was that it worked brilliantly, with some clear architecture in the links between clips, but otherwise no problem following the journey through Eno’s ideas-based art and production over the years. There were some odd choices in music mixing, but it all seemed to flow to some sort of conclusion and an understanding of Eno and his work.

Having the director on stage is handy: he does a post-movie Q&A. His take on the question of narrative is that humans are such natural storytellers that if you show an audience a complete random mess of clips, most would create a narrative to make sense of it. People tell him how well-constructed the documentary was in terms of story, even when it wasn’t. Humans find patterns in everything – this may well be how we manage to make sense of life in general, to find our place and tell our story in a world which is really just a mess of fluctuating quantum fields and particles that probably aren’t there. We all find patterns and create our stories. How’s yours doing?

Static versus dynamic art

One obvious limitation with Hustwit’s movie-making concept is that currently the director is required to tour with the movie, which dramatically shrinks its audience, even if you’re playing the Sundance Festival and the Opera House. But that’s no different to touring musicians on the road, or a theatre residency, even sport: for all these events it is the ‘being there’ which delivers the real version, while a concert on Blu-ray or sport on the TV is a simulacrum of the art – a recording, not the art itself. Only at events can things differ between each performance – new songs, a chat during tuning up, the variations in theatre which hold an audience in thrall, or the twists of Hustwit’s ever-changing documentary.

One cost of going from performance to mass market is that the art inevitably becomes fixed. Movies, as with books and recorded music, have developed into a static art form which is created to be mass-produced and hopefully mass-consumed.

When we watch Gone With The Wind today, we may gawp at its stereotypes from another era, but we see exactly the same movie they saw in 1939. When you rewatch your favourite Star Wars movie, you don’t expect it to have a different outcome. If you re-read your favourite book, you’d be positively alarmed if it came out differently.

But what if it did? What if, like the Eno documentary, there was enough extra material available to switch up the story, and some mechanism by which to do it?

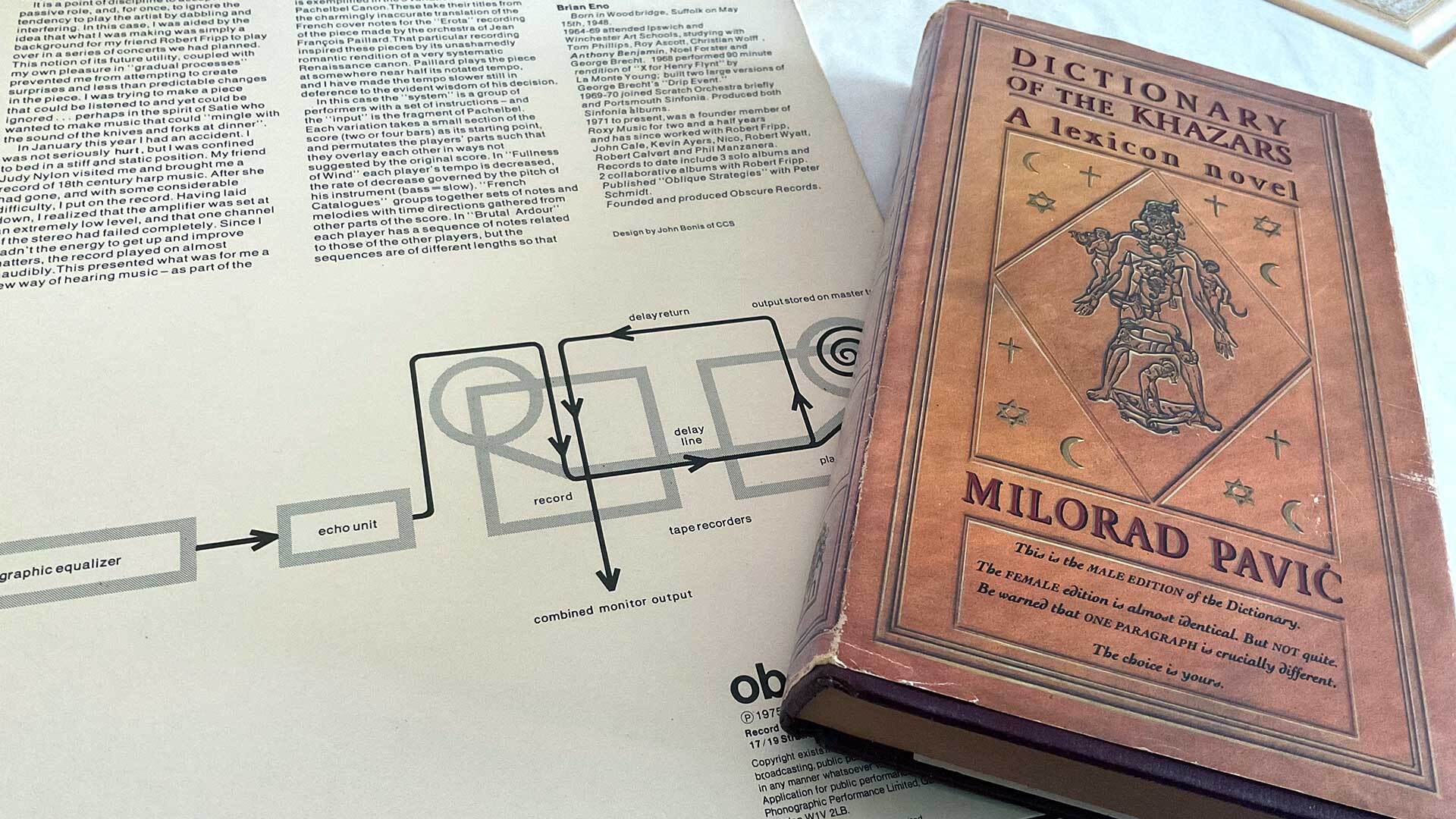

This has been tried to some extent in literature, and even in recorded music. I remember the wonder of reading Milorad Pavić’s Dictionary of the Khazars when it was published in English in 1988. Though classed as a novel, it is presented as three cross-referenced mini-encyclopaedia (also issued in male and female versions which differ only in a single paragraph). You find your own way through the entries, bouncing between references as plot lines slowly reveal themselves. It’s intriguing, and you’re never quite sure when you’ve finished it – I still have my copy, just in case I haven’t.

Jack White had a go at non-static art on his Ultra vinyl version of the ‘Lazaretto’ album: in addition to 45rpm and 78rpm tracks hidden under the label, an angel hologram appearing above the disc when playing, and side one playing from the inside out instead of the outside in, he fashioned side two so that the first song has two grooves spiralling inside each other, so that you get either an acoustic or an electric version of Just One Drink depending on exactly where you dropped the needle and so which groove it entered. Again, art which is potentially different every time – if within rather limited parameters.

White’s trick reminded me of a 78rpm disc we had in my childhood on which there was a recording of a horse race; it came with a little betting chart, and you could bet on one of six horses. You might think that, besides encouraging kiddies early into the joys of gambling on the gee-gees, this might be a rather boring game if you had already played the record. But there were six different grooves on that disc, all inside each other and each different at the end with a different winner. Even the most observant would-be race-fixer faced great difficulty in dropping the needle into exactly the right groove while the disc was spinning at 78 rpm. I know because I tried.

Future movies

The idea of having a movie change each time seems near-impossible using conventional delivery as it stands today.

To put Hustwit’s ever-changing Eno documentary on a Blu-ray you might use branching to switch between sections, but there’s simply not the space to store 500 hours of source material between which to switch.

Could it be streamed? By which I mean not like Hustwit’s upcoming curated 24-hour event, but on demand, like Netflix? Could the provider store the entire video archive of clips and then serve them up under some moderately intelligent delivery system? Not impossible, but complicated; you can’t imagine they’d be up for it for a single film.

For a documentary, of course, it is normal to have far more footage than you actually use. For an action movie, not so much – they don’t go lavishing special effects on many sequences which don’t make it into the final cut. Creating enough spare footage for variable endings and different viewpoints might be utterly impractical for such movies, as well as requiring entirely new ways of doing things.

But of course games are already doing it. Gaming is already a major generative art form which is different every time. Game designers are entirely au fait with the ideas of multiple endings, different viewpoints, different paths through a narrative, all unfolding in real time under a directorial guiding hand.

So all the skills are available. The limitation is on the computational power available, and on the ultimate quality of presentation. Computer games get more gobsmackingly visually amazing every season, and more powerful with every console generation. So when we reach the point where computer generation can present a believable movie world, what’s to stop movies being similarly controllable by the viewer? We’ve been waiting decades for computer animation to cross the Uncanny Valley into the sunlit uplands of realistic actor generation, but with the exponential rise of Artificial Intelligence in image and video creation over the last two years, we must be very very close. The film and television industries are already abuzz and afear with actors discussing their digital image rights: Black Mirror’s ‘Joan Is Awful’ episode makes a compelling presentation of the near future. Meanwhile AI has proven so adept at generating ideas, plot lines and dialogue that it took a year of Hollywood strikes merely to establish how it might and might not be used in the movie-making business. For now.

From the Q&A at the Opera House, it was clear that Hustwit believes there is a future for such generative changing movies. His collaborator Dawes talks carefully about innovating with generative software and AI “as a way to enhance human creativity, not replace it”... working “in a filmmaker-focused and ethical way”. But I don’t think they’ll be auto-edited from vast collections of pre-prepared footage. I think the AI banks will soon burst and we’ll have movies generated instantly, perhaps according to rules laid down by a director, but variable according to the whims and inputs of the user. If we have enough generative power in the home we might do this on the spot; otherwise the streamers will do the crunching and then serve a fresh movie to each consumer, reacting to their input as it goes.

To this new experience we may soon add projectors that fill three walls rather than one (already under development), or 3D goggles (yawn), or TV-like screens that are painted onto all your dry-wall surfaces (not yet developed, but I’m thinking about it hard). We can then stand in the movie, control the movie, become the movie.

And instead of arguing over the remote control, we can argue over whether to stop Oppenheimer from cheating on poor Emily Blunt, whether we keep Elvis alive a little longer to do the European tour, or whether Darth Vader should turn out only to be Luke’s uncle, and once removed by marriage, so he can marry Leia after all.

It should all be fantastic fun: we will play our personal movies on our personal holodecks immersed in our personalised narratives; we will forget all that is real, and it will be a complete surprise when the machines kill us all.

MORE:

14 exciting hi-fi and home cinema products we can't wait to review in 2025

New issue of What Hi-Fi? out now: stunning step-up turntables, bang-for-buck stereo amplifiers, TVs and more

LG C5 preview: what we expect from LG's popular OLED at CES 2025

Jez is the Editor of Sound+Image magazine, having inhabited that role since 2006, more or less a lustrum after departing his UK homeland to adopt an additional nationality under the more favourable climes and skies of Australia. Prior to his desertion he was Editor of the UK's Stuff magazine, and before that Editor of What Hi-Fi? magazine, and before that of the erstwhile Audiophile magazine and of Electronics Today International. He makes music as well as enjoying it, is alarmingly wedded to the notion that Led Zeppelin remains the highest point of rock'n'roll yet attained, though remains willing to assess modern pretenders. He lives in a modest shack on Sydney's Northern Beaches with his Canadian wife Deanna, a rescue greyhound called Jewels, and an assortment of changing wildlife under care. If you're seeking his articles by clicking this profile, you'll see far more of them by switching to the Australian version of WHF.

-

ikester8 Thank you, Mr. Ford, excellent review of the varied technologies of generative entertainment inspired by the Eno documentary. There was one additional randomized floppy-single-vinyl recording from Mad Magazine called "Super Spectacular Day" that had, IIRC, six different songs that all started the same, describing a wonderful day, then changing halfway through to describe how the day went all wrong in the different versions.Reply

I saw the Chicago premiere of Eno and am looking forward to (some of) the 24-hour event this month. -

Jez Ford Cheers Ikester8, appreciate the feedback - I'll be putting the Mad single on my collection list! (And I used to share an office with Australian Mad, darn it...) Yes, 24 hours of Eno here we come! It looks like if you sign up for the site's subscription for a month, you could enjoy it at half price... just sayin'...Reply -

John AH As a long-term Eno fan back to the Roxy Music days, I'm equally interested in his activities. I think my favourite remains the Generative music software he made that in theory produced ever changing music, but didn't age well. Netflix tried the concept of different endings but it didn't catch on and only Black Mirror: Bandersnatch remains. People also attempted multiple endings using hypertext based Hyperdrama, which died a death. The reason? Writing is hard and coming up with compelling stories even harder. AI can churn it out but there's no wit, imagination or hours in the day to waste on it. Unfortunately the 24th coincides with a concert of Mahler, Vaughan Williams and Kaija Saariaho’s final work Hush. Think I'll prefer one original that day.Reply