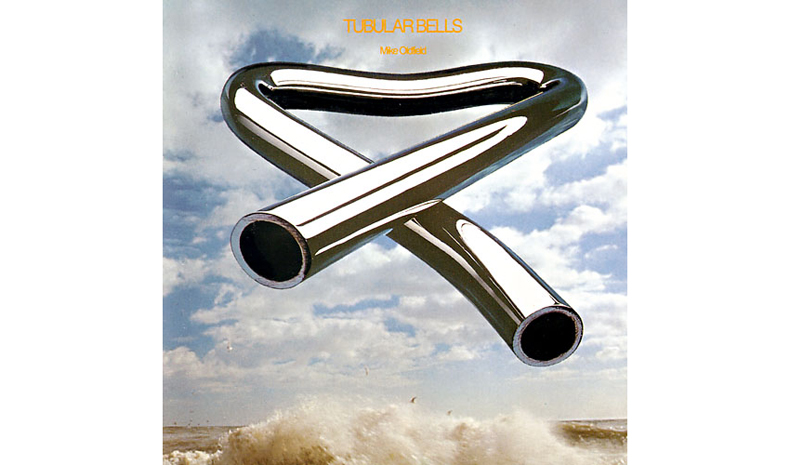

How Tubular Bells built the Virgin empire

It's possible to draw a direct line from an LP deemed utterly uncommercial to a company prepared to put tourists into space.

“Right after I’d finished it, I didn’t want to know about it,” Mike Oldfield says of Tubular Bells. “It was such a big thing, I’d got it out of my system and, for about five, even ten, years I didn’t want to know about it.”

During the decade after its release on May 25th 1973, Oldfield recorded a further seven studio albums, and released another in 1984. None, though, to the acclaim of their forbearer, the biggest-selling instrumental album of all time.

In the same period Virgin Records became an international player, with Richard Branson adding Virgin Vision and Virgin Games imprints to the arsenal. In 1984 he launched Virgin Atlantic Airways and the following year Virgin Holidays. While Oldfield struggled to come to terms with his masterpiece, the company it had built was already well on its way, literally, into space.

There is barely a facet of these intertwining stories that isn’t extraordinary. Let's begin with Oldfield’s prodigal talent as a teenager: his first flirtation with the record business happened aged 15, as guitarist in a folk duo with his sister Sally named The Sallyangie.

Music journalist Karl Dallas, who met him at that time and interviewed him subsequently upon the release of Tubular Bells, offered probably the frankest summation of Oldfield’s character as a teenager. “He was such a precocious little pr*ck, he really got up my nose - but they had such a great deal of potential.” Oldfield was very good, and he knew it.

But Oldfield himself says that by age 17 he felt as if it were the end of the world for him. He had shared a flat and a band, The Whole World, with former Soft Machine vocalist Kevin Ayers, but several disturbing LSD experiments left Oldfield feeling unstable and more ready to retreat into himself and his music.

Following that relationship Oldfield became much more willing to focus on creating his own music - or, rather, he became unwilling to do anything else. Ayers had gifted him his tape recorder, with which Oldfield began recording the first Tubular Bells demos.

Get the What Hi-Fi? Newsletter

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

The old story followed. Record company executives found it easy not to sign him, not least because his piece contained no vocal or drums. Oldfield found himself working as a session musician at Branson’s Manor Studio in Oxfordshire.

For his part, Branson (aged 19 at the time) had achieved little success with his magazine Student and was meeting some legal opposition to his mail-order record service - he was essentially importing vinyl with a somewhat lenient view on taxes and selling at a price 10% lower than the High Street. Now he opened his first record shop on Oxford Street.

The Manor was not purchased through business gains – Branson was living on a houseboat at this time – but with two mortgages, one of which came from his aunt (who rather uncharitably charged him more on his repayments than the bank did). But it was here Oldfield made his demos heard and, on the advice of Simon Draper, Branson allowed Oldfield into the studio between sessions to record his album.

Perhaps not appreciating quite the character with whom he was dealing at this point, Branson told Oldfield to write down the instruments he needed “and we’ll get it for you”.

There are ten instruments played by Oldfield on Tubular Bells, from Spanish guitar to glockenspiel, via timpani and tin whistle. Tubular bells, however, were not on that initial list.

If you really want to draw a Virgin Group family tree, you probably need John Cale near the top as well - it wasn’t until his instruments were being wheeled out of the studio to make room for Oldfield’s that the latter spotted the bells and demanded they stay. What might our rail network or airline choices look like now, had Oldfield released an album named Flageolet instead?

Nine months of writing (on cigarette packets) and recording (in the studio) later, Tubular Bells was complete. Branson went abroad in an attempt to secure licensing deals, only to be met with the same requests for vocals. The only voice on the record - decidedly crackpot “Master of Ceremonies” Vivian Stanshall - introduces different instruments.

Regardless, on 25th May 1973 Virgin Records released Tubular Bells as V2001 - the company’s debut LP was a single instrumental piece across two sides of vinyl.

Driven largely by word of mouth, though helped immeasurably by John Peel deciding to play it in full on his radio show, over the following months it crept up the charts to secure its place in British music history. Ultimately Tubular Bells sold in excess of 15 million copies worldwide.

The mesmeric effect of this piece, with its bars alternating in time signature between 3 /4 and 4/4, was spotlit by its use in the film The Exorcist later that year. Its motif is used so sparingly, yet has somehow come to be regarded as the movie’s soundtrack.

There are other records to whom Branson owes a lot, of course – had he not signed punk acts such as The Sex Pistols when Virgin Records needed a shot in the arm a few years later, its light may well have dwindled and ceased – but Tubular Bells was undoubtedly the start of it all.

Two teenagers with less in common you’d be hard-pushed to find, but the result of that marriage of character and talent we're unlikely to see again.