How HomePod was made: a tale of obsession from inside Apple’s audio labs

When Apple invited us behind the scenes at HomePod Development HQ, we suspected the company was serious about sound quality. We didn't realise just how preoccupied it had become...

We now know the Apple HomePod sounds great, but before its launch that was far from a given. The company had already had a stab at speakers in 2006, with the iPod Hi-Fi – a product that received a three-star verdict from this publication.

But right from the start there were signs the HomePod was a different proposition. Not only was Apple taking audio seriously, but the company also believed it was developing a product that genuinely sounded great.

An early sign came at the company’s annual WWDC event in June last year. Apple not only announced the HomePod, it offered What Hi-Fi? a demonstration of its sonic capabilities. Not just in isolation, either, but against a number of rivals - including the Sonos Play:1, one of the best sounding wireless speakers around.

The early verdict was that Apple was onto something quite special. But a noisy exhibition floor is never the best place to appraise a speaker - more telling was that Apple was confident enough to invite the comparisons.

Then came an invitation to travel to Apple’s home in Cupertino to meet the team and tour the labs that birthed the HomePod, and to hear it before it hit shops. That was a bold move: you don’t invite What Hi-Fi? to listen to your product unless you think it sounds great.

As we now know, Apple’s confidence was well-founded. And as we now know, HomePod's success comes from Apple throwing a large portion of its considerable might behind the project, building new facilities and a new team with the sole aim of making the HomePod a smart speaker with serious sonic credentials.

MORE: That Was Then... Apple iPod Hi-Fi review

Get the What Hi-Fi? Newsletter

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

The Lab

Apple’s audio lab isn’t part of the company’s huge new Infinite Loop campus. Instead it occupies an anonymous building in one of the blocks in the vicinity.

There to greet What Hi-Fi? are some of the key figures involved in developing HomePod: Kate Bergeron, Vice President of Hardware Engineering; Gary Geaves, Senior Director of Audio Design and Engineering (and Bowers & Wilkins alumnus); Phil Schiller, Senior Vice President of Worldwide Marketing, who you may recognise from the livestream of Apple product launches.

Bergeron kicks things off, explaining the team has been working on HomePod for around six years. It began with the goal of creating a speaker “whose sound quality was independent of the room in which it was used,” she says.

The team quickly settled upon an array design which gave a level of control over the sound field which can’t be attained by traditional speaker layouts. “We are able to cover 360-degrees of the room and adapt as we see fit,” says Bergeron.

But settling on an array design was just the start of a process that initially involved a small team of experts testing, prototyping and measuring any number of iterations in the quest to find something worth pursuing.

The team took its winning prototype to Apple’s executives, including Schiller, and once given the green light the small, focused team was able to draw upon Apple’s wider resources, bringing in members of the Extended Software, Wireless Design and Manufacturing teams.

But even with a prototype that sounded great, the product was far from finished. “Acoustics are of course the highest priority for HomePod, so we hold that as the gold standard,” says Bergeron. “But we have to consider things like the thermal design of the system and overall power, and then compute what it takes to run the product. We also have to look at wireless, because it has to perform well, and the various sensors in our product – we have to make all of those work, too”.

MORE: Best speaker deals - hi-fi, Bluetooth, wireless

At this point, What Hi-Fi? is invited to cross the threshold into the lab proper, to see a deconstructed HomePod for the first time. Bergeron explains each of the components, starting with the seven tweeters arranged in a ring along the bottom of the HomePod: “The tweeter is an optimised folded horn array and the sound flows out through the enclosure, which is why you can’t see the diaphragm - but it’s all highly tuned to make it sound as great as possible,” she says.

Then there’s the woofer, which is significantly weightier and more robust than you might expect. Much has been made of this driver’s ability to travel 20mm between peaks but, as Bergeron explains, it is mounted on dampers so the intended vibration from the sound isn’t transmitted into the final product. “That would cause unwanted rubs and buzzes,” she says.

What’s interesting about the HomePod is that Apple began with a clean slate, but ended up with the tweeters at the bottom and the woofer above – the opposite of traditional speaker design. “By putting [the tweeters] on the ground, we shoot them out more parallel to the surface, which means less reflection,” Phil Schiller explains.

“Traditionally with a tweeter, you’re trying to fill the room as much as you can with that horn because, being high frequency, it has limited range,” says Schiller. “We’re trying to do the opposite, to actually direct each tweeter. If you’re trying to get that perfect control of sound, this is a better arrangement.”

As well as the deconstructed HomePod, What Hi-Fi? is also shown the microphones, six of which are wrapped around the circumference of the product, and the logic board that houses Apple’s A8 chip, the same processor used to power the iPhone 6 and 6 Plus.

“As a mechanical engineer”, Bergeron said, “I like to joke that my job is to shrink that down as small as possible and make the electronic engineer’s job really hard by taking away all the space.”

Above the logic board at the top of the HomePod are the antennas which make it wireless, and the whole thing is wrapped in an acoustic fabric mesh designed in partnership between Apple’s industrial designers, the Acoustic team and Soft Goods team. It essentially stretches over the shell of the HomePod.

MORE: 31 Apple HomePod tips, tricks and features

On tour

Gary Geaves takes What Hi-Fi? on a tour of the site, and begins by explaining how the team has expanded over the years. He thinks Apple may have the biggest acoustics team on the planet, with experts from many audio brands and universities on board.

“The reason that we wanted to create this team was, firstly, to deliver on products like HomePod, which many of the team were excited and passionate about - but also to double-down on audio in all of our products,” Geaves says.

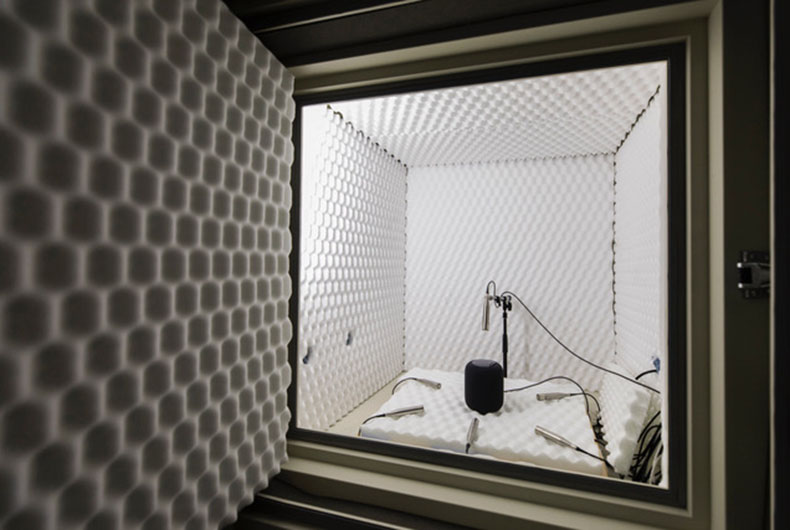

For the planet’s biggest acoustics team, the lab we began in seems somewhat under-populated. But while a lot of the HomePod ‘heavy lifting’ was done here, the larger team works in the main room. This lab has a number of small sound chambers along its right-hand side (the last two amusingly named ‘Nook’ and ‘Cranny’).

These are basic chambers that sit on the ground and are often used for telephony tests to ensure all of Apple’s products conform with the industry standards. They can also be used for testing active noise control in phones, and the algorithms that compensate for how you hold your phone and the distance from mic to mouth. All interesting stuff, but not really what we are here for.

But then What Hi-Fi? is shown another smallish chamber buried into the ground and dampened with foam. This is where the HomePod testing began and is certainly of more interest to a journalist from an audio/visual publication.

“We would measure the speaker in this anechoic space, but then also add in artificial walls so we could understand in simple terms what the algorithms were doing when there was just one wall,” explains Geaves.

“Then we’d add another one, and gradually take it out into the real world, which is a much more hostile place for a speaker like HomePod because there are many different kinds of environment that you have to make sure it works well in.”

While this chamber was responsible for much of the HomePod grunt work, particularly in terms of tuning its response to reflections, it’s far from the biggest weapon in Apple’s arsenal.

That accolade goes to the next stop on our tour – an anechoic chamber purpose-built for HomePod around six years ago. Geaves believes it is one of, if not the, largest of its type in the US.

Sonos’s anechoic chamber in Boston might give Apple’s a run for its money for sheer size, but that’s not to take anything away from just how impressive this room is. As is the norm for anechoic chambers, the walls are lined with foam wedges designed to absorb the sound from the speaker and remove reflections so that engineers can properly measure what the speaker itself is doing.

Sitting on big isolating mounts and isolated from the building around it, this is a room within a room. Even the pipes carrying cables from the main building into the chamber have gaps to ensure they don’t carry vibrations and colour the measurements.

“These rooms are an essential part of all audio and acoustic development, but especially so for HomePod,” says Geaves. “We’re interested in directional behaviour and directional control, which are critical to the speaker, especially because it has to adapt those things when it’s in different kinds of environments.”

In the centre of the room is a HomePod on a pedestal, with an arc of speakers and microphones suspended above. “Those two things, coupled with a turntable that moves 360 degrees, allow us to work out what’s happening to the speakers and microphones in the HomePod in a full, spherical space,” Geaves adds.

The size of the chamber is important in that it allows the team to get clean signals so they can measure down to 20Hz – the lowest frequencies humans can hear. Careful design of the wedges means they can get clean signals up to 20kHz, the high end of human hearing. “We cover the entire range,” says Geaves.

But the room is only part of the picture. As Geaves explains, it would be nothing without the custom software, devised by the HomePod team. That not only controls the equipment within the chamber (the computers are kept outside for obvious reasons) but also “has special processing and special ways of visualising those results and that data,” he says.

The room is designed so the team could derive what Geaves calls the “ground truth” of the HomePod. That information was then passed on to sound tuners who would “tune to taste”.

“We have an expert tuning team available to us,” says Geaves, “and a whole bunch of other listeners to make sure the product is not only moving in the right direction from an engineering perspective, but also from a taste perspective.” But to whose tastes, we wonder? We make a mental note to ask later.

The tour continues to a smaller chamber with a more specific function, the tuning of Siri and HomePod’s six microphones. These microphones work in unison with HomePod’s custom software to extract speech from a noisy signal. And there really is a lot of noise at play here: “Firstly, there’s noise coming from the speaker when it’s playing and you’re trying to get Siri’s attention. Then there’s people talking or other stuff going on, and also the effect of reverberations in the room, which can be problematic for voice detection algorithms.”

This chamber does without the scale, suspension and foam padding of the big anechoic chamber, but it’s similarly detailed in its design. In fact, it’s accurately modelled on the average characteristics of the rooms of hundreds of real-life Apple employees.

“What you’re hearing now in my voice, that echoiness is an average reverberation of those rooms we measured,” says Geaves. On top of that, background noise such as chatter can be pumped into the room for the HomePod to contend with. It’s all finely detailed and, frankly, obsessive.

MORE: Smart speakers - everything you need to know

Good vibes

The final stop on our tour of Apple’s audio labs is the Noise and Vibration team. This team has been around for 15 years, and was originally created to look at fan- and hard disk noise in Apple’s computers. It has since worked at reducing electronic noise from capacitors and the like, and more recently been used to help cut out electronic noise and unwanted vibrations from the HomePod.

Unwanted vibrations are of particular concern for such a small-yet-powerful speaker. Traditional methods of measuring vibrations were found wanting, so the company developed a set of ‘measurement metrics’ that better matched what you would actually hear.

It’s here the vibration isolation system was developed – including, presumably, the silicon ring at the base of the HomePod that has caused issues with some wooden surfaces. At the time What Hi-Fi? was shown around the lab, this problem had yet to surface - but given Apple’s meticulousness in all other departments, one has to wonder how this was missed during pre-release testing.

The noise aspect of the Noise and Vibration team’s work involves another large anechoic chamber – this time with a number of microphones that look as though they’re probing the HomePod’s backside.

“Here, we’re trying to pick up tiny electronic noises so we can figure out where they’re coming from and get rid of them. When you use HomePod in a quiet circumstance – say it’s just plugged into the mains and on your nightstand in your bedroom – we want no annoying noises coming from anything.”

MORE: How to choose the right wireless speaker

Of course, to measure tiny noises you need absolute silence, and the silence in this room is more absolute than anything we’ve ever experienced. With the door closed you can hear your own heartbeat. It’s an oppressive, claustrophobic silence, which is why Geaves keeps the door closed for no longer than five seconds.

If you want some crazy figures, how about -2dBa, which is the volume that the room measures at? Or 28 tonnes, which is the weight of the foot-thick concrete slab that this chamber is built upon and the weight of each of its metal walls? And then there are the 80 isolating mounts between the concrete and the room itself. It’s a fascinating feat of engineering and, yet, one of the most unpleasant rooms we’ve ever been in – and that includes festival toilets.

Apple has always touted its own obsessive approach to product design, but visiting the birthplace of the HomePod really does hammer that home. It’s not just the number of different chambers (neither Gary Geaves or Phil Schiller could give me an exact figure), it’s the way that each is designed and used in specific ways.

Having invested all of that money in measurement processes, hardware and software, we can’t help but be impressed by Apple’s insistence on the importance of combining that with real-world testing.

MORE: Best wireless speakers 2018

Best possible taste

Which brings us back to taste tuning. After all, taste varies from person to person, so how do you ensure everyone is pulling the sound in the right direction? What Hi-Fi? puts this question to Phil Schiller, and though he isn’t prepared to name the people involved on the panel of expert listeners (but confirms the Beats team contributed), he explains the instructions given to the taste tuners.

“What the team do is analyse each song and try to understand what it’s supposed to sound like in its purest form,” he says. “When we play it back on HomePod, we want to have a rich and natural mix to it. We’re not over-driving bright sounds, we’re not trying to throw some over-weighted bass across everything.

“There’s a limit to how much you can take advantage of the technology if all you’re doing is trying to be neutral,” he says. “We went for a rich, full sound, something that was extremely clean from low volume all the way up to 100 per cent. Something we thought best represented what the original recording was meant to sound like but that takes advantage of the full soundstage. Those were the goals,” he adds.

“Most speakers are tuned to one sound. But HomePod listens to every song and analyses it as it’s playing, so it can really do more to adapt to delivering what the song is supposed to sound like.”

At the time, even having heard the HomePod in Apple’s own demo, this sounds far too good to be true. But after reviewing the speaker in our own testing rooms, What Hi-Fi? has to concede that Schiller has a point. We are yet to find fault with its audio quality.

We’re not saying it’s time to throw away your traditional hi-fi. But the HomePod is a new and unique approach to the wireless speaker – and its undeniable sound quality is clearly the result of huge resources and an almost unhealthily obsessive approach to product design.

See all our Apple reviews

Tom Parsons has been writing about TV, AV and hi-fi products (not to mention plenty of other 'gadgets' and even cars) for over 15 years. He began his career as What Hi-Fi?'s Staff Writer and is now the TV and AV Editor. In between, he worked as Reviews Editor and then Deputy Editor at Stuff, and over the years has had his work featured in publications such as T3, The Telegraph and Louder. He's also appeared on BBC News, BBC World Service, BBC Radio 4 and Sky Swipe. In his spare time Tom is a runner and gamer.