The holy grail of vinyl: the art of half-speed mastering

What exactly does the process involve? Miles Showell reveals all...

This interview was originally published by What Hi-Fi? in October 2017.

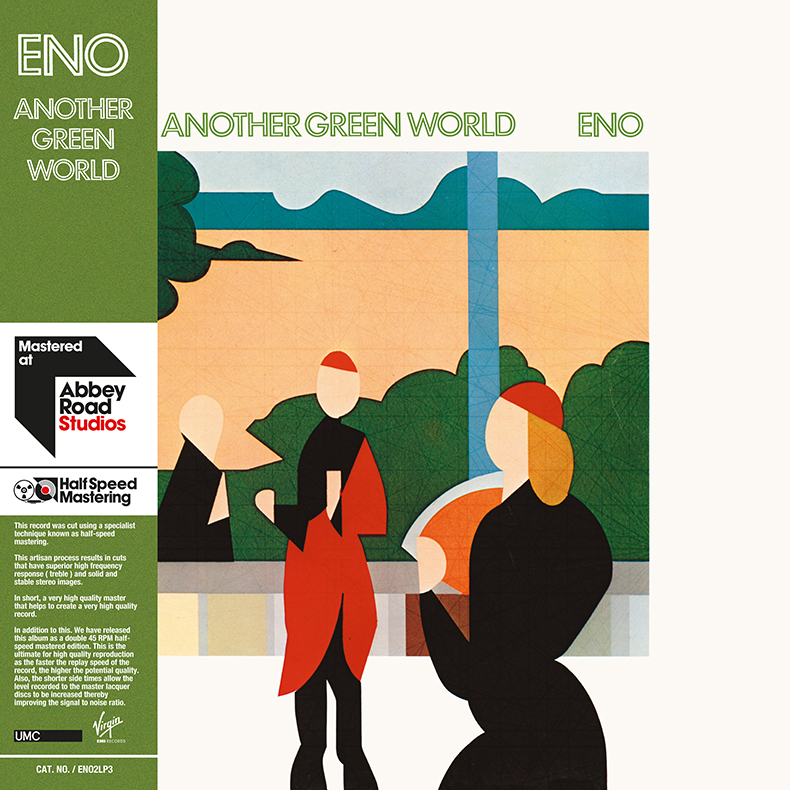

Miles Showell began his career in 1984, learning the art of disc cutting and tape copying. He joined Abbey Road Studios in 2013 and, as an expert in half-speed mastering, has remastered many of the world’s biggest artists, including The Who, The Beatles, Disclosure, Queen, Eric Clapton, The Rolling Stones and, recently, Brian Eno.

When Showell wanted advice on getting half-speed vinyl mastering going again, he turned to Stan Ricker, the engineer who pretty much wrote the book on the craft. Ricker, for his part, was astounded that anyone would want to try it again.

Cutting a disc at half speed not only takes twice as long, but requires a new method of working, with highly modified equipment. But, essentially, the non-stressing of any component in the process means half-speed mastering is the most accurate way to cut a record.

And when we travelled to Abbey Road Studios to listen to Showell’s recent work, remastering four of Brian Eno’s solo records at half speed, we understood it was all worth his efforts.

Here, he explains the whole process and how he helped it start again.

On the half-speed process...

“The Eno job is a good example, because I was given access to the original tapes – a couple of originals are missing, but mostly I had the masters. It’s getting increasingly difficult to get hold of original tapes now, because people are aware that continually playing old analogue tape is a bad idea because it starts to wear away.

Get the What Hi-Fi? Newsletter

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

"I have a fantastic Ampex tape machine, which just sounds gorgeous – I’ve got custom heads for it, which make it sound even better – so I was able to do a really nice transfer. I captured it at hi-res digital, 192-kHz/24-bit and, from there, did any repairs that needed doing. With clicks and extraneous noises, I had to do some de-essing to soften the ‘S’ sounds of the vocals to avoid sibilance on the pressings.

"When I did the transfer, I was only thinking of records: there’s no excessive limiting or extreme compression, which you might do for a CD release to make it sound loud. No need for that on records – full level digital is too loud to cut as is, anyway, so it’s completely pointless to add further compression and further limiting to only bring it down even more.

"The beauty of doing a high-resolution digital transfer is you can go in and micromanage the audio. One of these tapes had been played on a faulty machine that actually damaged it and left clicks all over it, so I went in and took out all the problems that had been created, which you couldn’t do cutting live from the tape. The only way you can fix that is digitally, and it’s next to invisible mending."

On the special equipment...

“Once I was happy with the files, I started with the cuts. I have a recently restored and customised Neumann lathe in the room, which is absolutely beautiful – the best I’ve used – and I have a customised RIAA amplifier and filter.

"If you’re cutting everything at half speed, you’re playing the source at half speed and running the lathe at half speed, then the frequencies and the filter are in the wrong place: you need a special one to do half-speed cutting.

"When you’re doing a half-speed cut, you can’t hear what’s going down because it’s all slow and just sounds awful. So we insist that every client has an acetate. I’ll sit down and listen to it end-to-end on a domestic deck to make sure it sounds okay – there’s no point playing it on high-end turntable, or even on the lathe pickup, because it doesn’t represent the real world.

"From there it goes off to the client, and if they’re happy I’ll cut the masters. In this case, they got shipped off to the Optimal plant in Germany, probably one of the two very best plants in the world, so I was delighted when it went there. Six-to-eight weeks later I get test pressings back.”

On smoothing the sharp edges...

“You do all the prep work first. I’ll go through and spend hours just checking things; I have to de-ess before I cut at half speed because the limiters don’t work. They’re looking for two things: listening for a specific frequency band, which obviously is not there any more; and also any acceleration, sudden fast transients it thinks are a bit sharp.

"Because you’re going so slow it shouldn’t have any sharp edges. So any vocal you think might cause distortion with your sharp, bright ‘S’ sound, I’ll have to pre-treat that. But in a way it’s good, because I can use a specific digital tool which will allow me to just find the ‘S’.

"Anything around it – any bright guitar or snare-drum hit or tambourine – is totally untouched, I’m just working on the vocal that’s going to cause a problem.”

On working at half-speed...

“Then it’s just a purely mechanical job to cut it at half speed, which is pretty dreadful to listen to when you’re in the room. I’ve had 12-hour days where it’s just non-stop and you walk out of here going stir crazy – but when you get the records back and they just sound so open and so fresh, it really was worth doing.

"All the hard work is done prior to the cut. Then I’m just checking that the lathe is working okay and the swarf, which is the waste product that’s being cut out of the disc, is going up the vacuum pipe alright and nothing looks untoward. Once I’ve finished, I can look under the microscope and check the groove is all fine.”

On the ultimate for vinyl...

“The problem we had with some of the earlier ones, in the 70s, was people would be doing it live from tape, which sounds lovely but they have a bit of a roll-off on the bass end, from 30Hz downwards, which is just a factor of the machine.

"Obviously at half speed that suddenly becomes 60Hz, so you ended up with these really clean, bright records with not much bass. The advantage of my method is that we have all of the bass and all of the top end, and everything just sounds nicer. Because nothing’s getting pushed to its limits everything sounds so much more real."

On sceptical colleagues...

“A couple of very good recording engineers I work with have been sceptical, and asked, ‘Will I really hear a difference?’. Then I’ve given them an acetate and they’ve said, ‘It’s like playing the master tape, it doesn’t sound like a record any more’. It just has this extra kind of ethereal air that you don’t get doing it in real time.

"Ultimately, it’s the non-stressing of the system that makes half-speed sound better. It’s not the speed of the lathe going round, it’s the fact you’ve reduced the speed of the music by a factor of two.

"In the mechanical system we’re using, the 600W amplifiers aren’t being pushed so hard, the cutter head hasn’t got to cut some nasty, bright high-frequency stuff that gets hot and stressed out. That’s where the gain is.”

On a better cutting speed...

“Cutting at 45rpm is better, because you can cut louder, and the faster the playback speed the higher the quality. You’ve got more vinyl going past your stylus per second than you would at 33⅓rpm, so everything will sound cleaner.

"The only disadvantage is you’ve got to get out of your seat twice as often to turn it over or change the disc. But half-speed is by far the most accurate way to cut a recording. If you can do it as a double album at 45rpm, that’s pretty much the ultimate you can get with records, there’s nothing else to squeeze out of the system.”

On catering for your audience...

“I usually test using the Technics LP-1200 I have in the room. It’s probably a bit more than mid-range, but we’re not talking a £50,000 esoteric thing – it’s got a fairly average £150 Audio Technica MM cartridge in. We deliberately haven’t gone for a reference pickup system because we wanted people with moderate to decent hi-fi to appreciate it and not to have any problems with tracking.

"If I had an amazing cartridge and the best arm and deck, I could cut far louder and not get any distortion, but that wouldn’t translate to enough people in the real world. To be viable, it needs to work for as many people as possible.”

On the quality of your deck...

“With any reasonable deck, you’ll be able to hear the difference in a half-speed cut, and obviously the better your playback system then the more you’ll be able to extract from the groove. When I was a kid, and I got into records 35 years ago, I got some of the early Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab pressings Stan Ricker cut.

"I didn’t have a great record deck in those days but it sounded better than normal records, and obviously as my system at home has improved, so has playback of those records. You don’t need the world’s most wonderful turntable to hear the difference, but obviously the better your system, the more you can recover.”

On the potential of half-speed...

"I’d love all records to be half-speed, but there aren’t enough engineers in the world to cut all the records we need anyway. We’re all snowed under with cutting, so if we did everything half-speed we’d need twice as many engineers and twice as many lathes.

"It’d be great if we could, but it’s just too much work. Also, it costs more money. It costs the client more than double, because of the extra time spent doing the acetate and everything else, so you can’t do it on a record that isn’t going to sell in big enough quantities.

"Ultimately, it’s a business, and the people issuing the record need to recoup their investment. There are a few other people doing half-speed mastering, but probably not as many as I do.”

View Showell's half-speed vinyl masters of Brian Eno's works on Amazon.