Clearaudio... a history and a new Reference

As the German vinyl meisters turn 45, we look at the history of Clearaudio and speak with Robert Suchy about the 'Jubilee' Reference

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This article originally appeared in Audio Esoterica magazine, one of What Hi-Fi?’s Australian sister publications, available in print and digital editions Click here for for a Readly special offer, including access to Audio Esoterica's digital editions.

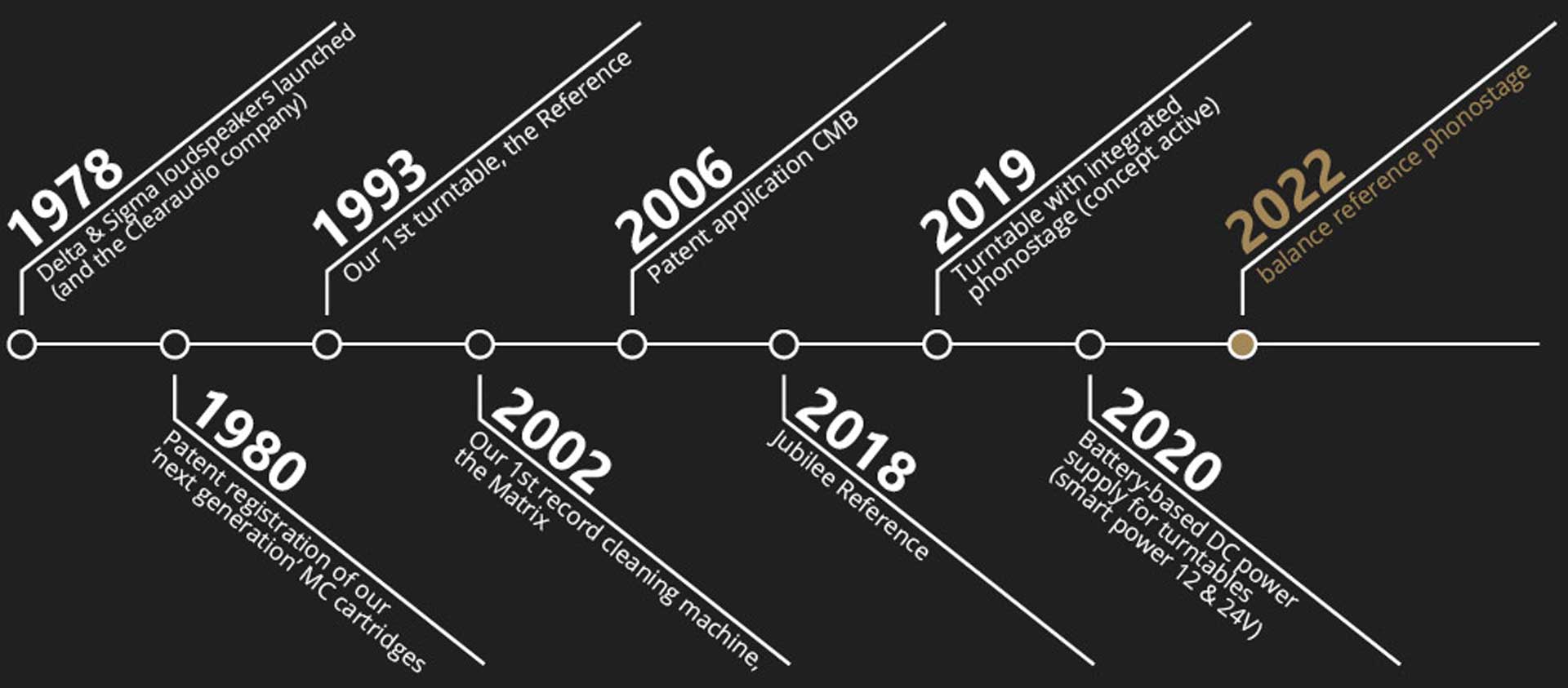

Clearaudio is turning 45 this year, for which we proffer our hearty congratulations.

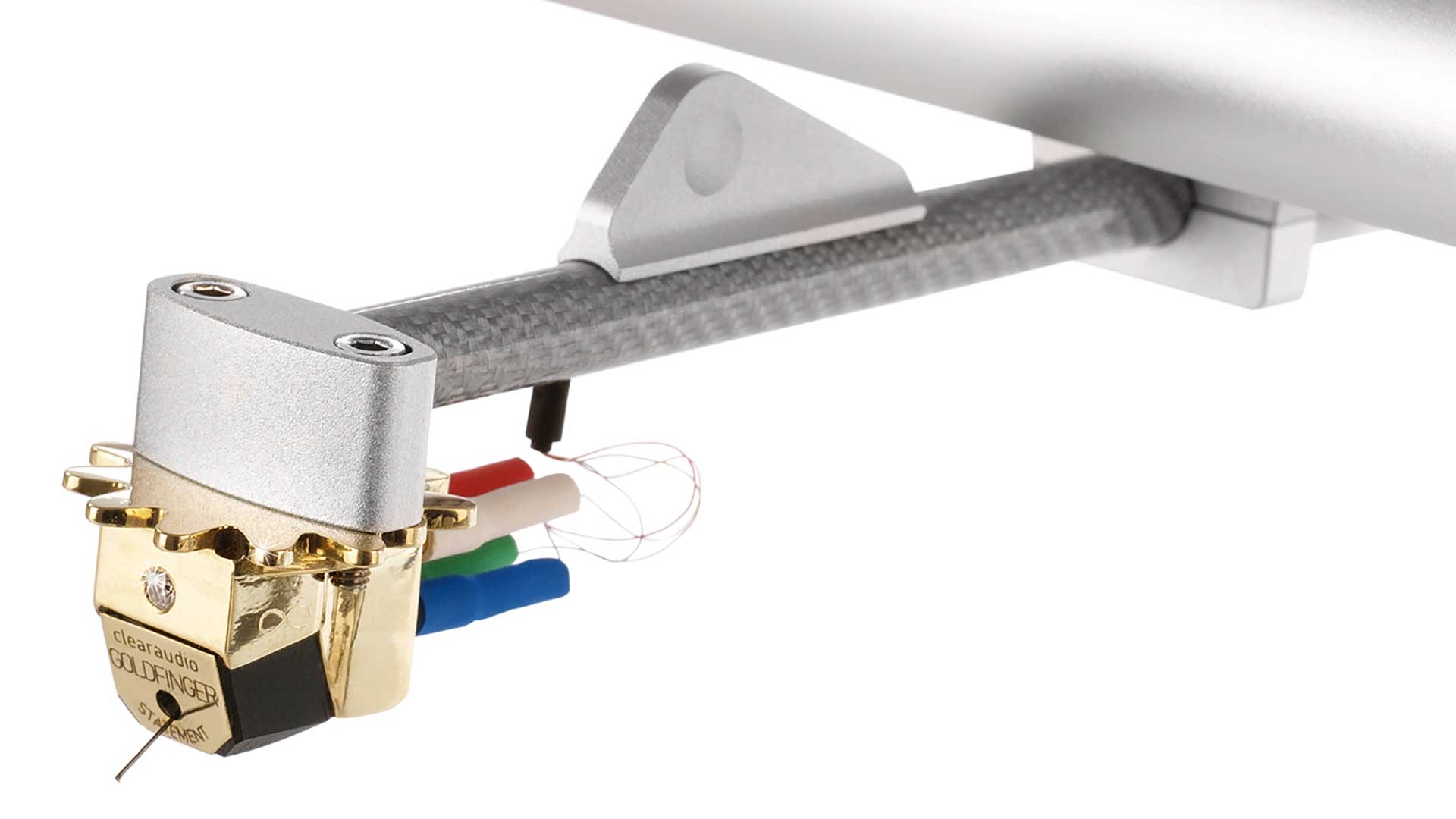

The German family-owned company has become a byword for analogue precision in vinyl reproduction, reaching for the musical firmament with products such as the Statement turntable, its linear-tracking tonearms, and the spectacular bling of the ‘Goldfinger’ moving-coil cartridge, but also trickling hard-won expertise down into turntables affordable to new vinyl fans and indeed those who have, like the company, made it through the years of the format’s decline to enjoy today’s glorious resurgence of all things groovy.

Among various anniversary activities, Clearaudio has been re-examining its heritage to produce the Reference Jubilee turntable, as pictured above. Clearaudio says it “marries the best of past, present and future to usher in a new era of analogue precision”.

The new Jubilee took as its starting point the company’s first-ever turntable, the 1993 Reference, and notably retains that deck’s unusual V-shaped chassis, but then loads up on the company’s latest and greatest technologies.

“The original shape is kept, but everything else is new and up to date,” Robert Suchy tells us of this turntable.

And showing how Clearaudio can do things rather differently, the Reference Jubilee includes (whisper it quietly) a digital-to-analogue converter, which is an odd thing to find on a turntable, and we bet you can’t guess what it’s doing.

We’ll come back to that later.

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

But Clearaudio’s team clearly enjoyed revisiting the brand’s first turntable design?, we asked?

“Yes, this was wonderful,” confirms Robert Suchy, “wonderful to show what is possible today by adding new materials and components, combining them with the original design to create a new one.”

In the beginning

Robert Suchy is one of three siblings – Patrick, Veronica and Robert Suchy, pictured above – who have run Clearaudio for nearly two decades now, since their father and company founder Peter Suchy “withdrew from active day-to-day business” back in 2005.

That was 28 years after the company’s founding in 1978, which Clearaudio’s history notes as “the year our first moving-coil cartridge was developed and patented”.

But in fact, Suchy the elder’s first products were loudspeakers, called the Delta and the Sigma. In this, Clearaudio’s story appears superficially to resemble the many speaker companies that began as ‘garage businesses’, usually by a musician/engineer – and yes, Peter Suchy had been in a rock band back in Prague.

But from the start there was evidence of a difference here, and of Clearaudio’s future direction.

There was, for example, an early involvement with Dr. Ernst Weinz in the development of the Weinz ‘Paroc’ (parabolic oval cone) diamond stylus, the first to use a boron cantilever. The early Clearaudio released a ‘Trygon’ parabolic stylus, the first of a series. Such precision engineering showed something beyond other speaker manufacturers who were reading up on their Gilbert Briggs and banging some cabinets together.

But then Robert Suchy was no house-and-garage engineer. He was born in South Bohemia, in what is now the Czech Republic, a little over an hour south of Prague, where he went to study nuclear engineering. Following 1968’s Prague Spring he came to the west and found work in Germany on ship-based nuclear reactors, and then for Siemens-KWU on fuel rods for pressurised water reactors. (Presumably successful: there are currently seven Siemens-KWU reactors operational across Europe and Argentina.)

After handling delicate systems like nuclear fuel rods, a little stylus design must have seemed a relaxing occupation, and one serving pleasing musical ends. And even with speaker design Peter Suchy wasn’t just banging boxes together; he was involved in the intricacies of designing an ultra-low-distortion tweeter.

Robert Suchy describes his father’s switch from loudspeakers as a realisation of the importance of the source-first philosophy which had swept through hi-fi in the 1970s – notably driven, of course, by turntable manufacturers.

“In the 1970s, good hi-fi was an important part of a great many households, and a hobby for many,” he says. “It had been quite a challenge to produce good speakers. But pretty quickly we realised that the source is the most important part of the system, the ‘First Player’, if you like. That‘s why Clearaudio switched quite quickly to its first patented moving-coil cartridge design.”

From carts to tables

Judging from the patent listings, by 1980 Clearaudio was on a roll. There was one patent for a ‘quartet magnet circuit’ for moving-coil pickups; one for a dynamic pick-up system; and another for a pick-up assembly “with induction coils joined to a needle carrier and fixed in permanent magnet yolk”.

“My original patented symmetrical MC design was about balance – electrical, magnetic, and mechanical,” Peter Suchy told Jonathan Valin in 2018 when he was being inducted in The Absolute Sound’s High-end Audio Hall of Fame. “The cartridge is unique in many regards including its use of independent coils for each channel – not both stereo channels on a single armature. My original design used four magnets, not a single magnet with pole pieces. Unlike the typical suspension tie wire, I designed a fulcrum-balanced suspension.”

The world’s first fully symmetrical moving-coil system impressed the hi-fi world in 1980, and from there the list of landmarks extended onward – the world’s smallest high-end phono pre-amp in 1984, a patented ‘Optimal Connection System’ for audio cables in 1985, and the crucial acquisition of patents and licences from Souther in the US for its linear tracking tonearm.

Among all this, one key event was the relocation in 1983 to Erlingen, where Clearaudio still resides, now located in the Meilwald nature reserve, “pioneering ecological sustainability”, its website notes.

It is also usefully able to benefit from proximity to the Frauenhofer and Max Planck Institutes (both in Erlangen), and Friedrich-Alexander University too. We asked Robert Suchy how the company makes use of these resources.

“Since Erlangen has a great University, the foundation in research for these Institutes is very good,” he tells us, “and that means we benefit from engaged students who may start working for us during their study. The chances that some stay with us are very good, something which gives our company a regular nice young push of energy.”

The strong technical foundation in Erlangen allowed Clearaudio to make ongoing investments in its own production capabilities, as the company increased its independence from the vagaries of third-party supply. It began producing even precision components in-house, and the company boasts that “when standard measurements are insufficient to meet our needs, our in-house engineers develop our own measuring devices”.

Clearaudio sees this as a key philosophy: it can ensure consistency through quality control, careful documentation, and results tracing.

A new Reference

By the time Clearaudio had all the elements in place for its first turntable, Robert Suchy had already joined his father’s firm as a precision mechanics apprentice. The Reference was launched in 1993, with its unusual resonance-optimised shape, and clearly displayed Clearaudio’s dedicated to materials.

It was made from acrylic and featured brass metal parts (later stainless steel), distinctly placed feet, heavy arm pillars and resonance control weights.

But enough of the nostalgia – the 1993 Reference turntable has now been reborn in the new Reference Jubilee (pictured above and below), a limited edition of 250 pieces. As Suchy says, the original shape is kept but everything else is new and up to date: it references the past albeit showcases the company’s present skills.

So Clearaudio’s patented (2006) ceramic magnetic bearing is here in a special variation for the main platter, while the lower drive platter has an inverted bearing. But it’s a new air-core (non-magnetic) DC motor and motor control system in the Reference Jubilee which has the company buzzing, one staffer calling it ‘the beginning of a new generation of motors and motor electronics’.

“The new control board design certainly makes it unique,” Suchy tells us. “There is a D-to-A converter built in, which creates a reference voltage, and we are combining this with the analogue control section; we check both speed circuits, so we get a much more accurate speed stability and fewer corrections of the motor in general.

“With this design we can control any ongoing imperfections that might arise just through wear and tear, as well as temperature drifts, which do not create issues with our design.

“Also the motors are that strong – enormous torque – that the tables behave like direct drive. It’s certainly one of a kind.”

To expand on that description, the 12-bit DAC isn’t doing any converting; it’s being used to generate a reference voltage for the drive motor’s (purely analogue) control unit. This works in tandem with the company’s optical speed control system, where every three seconds a sensor reads a strobe to establish the sub-platter’s rotational speed, feeding that back for the control unit to correct any deviation. At initial start-up it should self-regulate to perfection within 30 seconds.

Also unusual is the way the motor housing is elaborately decoupled from the chassis by “an elaborate network of rubber ‘tightropes’”, as they’re described in one place, elsewhere as “18 rubber bands”, ‘O-rings’ and, best of all in German, as ein Zusammenspiel von Gummibändern.

What’s the structure of this ‘Innovative Motor Suspension’?, we asked Suchy. Is it a series of circular bands surrounding the motor, or some interwoven Gordian knot suspending it? Is it all good to survive Australia’s tropical conditions?

“It is a rubber O-ring construction,” he says, “and since we have a long history with belt-drive systems, we are using rubber that has a higher silicone value, so they will last very long. But if something were to happen, it’s also easy to swap out.”

The Reference Jubilee can be purchased without tonearm or cartridge (£17,500, A$30,499), with a Clearaudio pivoted arm (seemingly the default system in the US, at $30,000), or with a tangential arm (A$44,999 in Australia, including cartridge).

We presumed that Suchy would pick the tangential arm by preference, and we were right.

“Tangential tonearms are by nature theoretically the better solution,” he confirms. “I would always prefer it in my playback system. But historically they haven’t been ‘in vogue’, and we have concentrated on higher-end tangential tonearms, where we have created trouble-free designs. But of course then these are not for everybody‘s budget, which is sad.”

The acrylic plinth of the original Reference has gone, replaced by one of Clearaudio’s secret weapons: Delignit Panzerholz. This is made by bonding beech hardwood veneers with phenolic resin and then ‘densifying’ the panel. Turntable aficionados will note the phenolic resin as much used by another turntable company, Rega, whose Roy Gandy cannot complete a turntable without a few ladles of phenolic resin in there somewhere.

By ‘densifying’ the hardwood and resin, they mean compressing it down to just half its original thickness under massive pressure.

The result is so dense that it’s bulletproof, and the official specs sheet of Panzerholz even goes so far as to assure us that 35mm thickness is enough to protect against a DM51 hand grenade with an amplified explosive charge at 5cm distance. (You can build a whole house out of Panzerholz panels should you be particularly worried about your neighbours.)

In turntable terms, it’s the density and rigidity of the material which does the job: Penzerholz beats aluminium for acoustic damping and much else. And for good measure, the Reference Jubilee laminates the Panzerholz to aluminium. So why, we asked, are the two combined?

“There are some secrets which we have discovered during our long history in designing analogue products,” says Suchy, “and some of these are related to the right material combinations, as well as shaping. The Reference Jubilee is such a creation!”

Other creations

Such a creation indeed. Clearaudio has a good many of them, most famous of which is perhaps that Statement turntable above, currently available from £136,500 / AU$226,999), described by no lesser authority than Australian Hi-Fi's Greg Borrowman as “without any shadow of a doubt the finest turntable in the world” (though we aren’t sure when he said that).

Unless you’re considering playback using a Neumann cutting lathe, he might also have called it the heaviest turntable in the world, given that the Statement weighs in at 350kg – without a tonearm.

The original Statement turntable arrived in 2004, a year after the iconic ‘Goldfinger’ moving-coil cartridge (above). It’s aptly named, housed in a 14-karat gold body, doubling up the number of magnets from the patented four to eight, for an even more homogenous flux field.

As Suchy mentions in the rest of our interview (see below), that gives Clearaudio a virtuous circle: a better turntable enables better cartridge development, and vice versa.

And with the big ‘50’ coming up for the company in 2028, we can safely assume that some junior technician in an Erlangen laboratory is currently fiddling with something that will eventually find its way to market as another patented Clearaudio wonder yet to come.

Bonus material

To put this article together we threw Robert Suchy a fair wealth of questions both general and technical, and many of his more specific answers are included in our main article. Here is some of the more general conversation. (Interview by Jez Ford.)

AUDIO ESOTERICA: Congratulations on Clearaudio’s 45 years! With you as one of three next-generation siblings in the business, Clearaudio is the very definition of a family firm – is that something that can be maintained in today’s corporate world? Do you have grandchildren in training already?

ROBERT SUCHY: Thank you very much! Yes, 45 years can be considered something special in this day and age, I would say. Since we, the three children, Veronika, Patrick and Robert, took complete operational responsibility more than 15 years ago, we’ve maintained the company’s heritage quite well, we think, and have established our products and quality in the high-end industry.

As for ‘The Next Generation’ – which will be the company’s third – they are still in school and will need more training! So while we can not say the future is secured, we are certainly working on it. For sure, they live – and they are listening to vinyl!

AE: How important to the company are reference products like the Statement and the Goldfinger?

RS: For us these products are like the Maybach Series for Mercedes. We can show what we are capable of in terms of technical solutions and build quality or design concepts. And as with Formula 1, there are always some ideas which can be trickled down into other product series. So our other product ranges benefit from these statement products as well.

AE: Have better cartridges driven you to develop better arms and turntables, or the other way around?

RS: Yes, both! When you’re always looking for where and how improvements can be made, you need better and better equipment in order to reach new levels. I would call it a process of natural evolution, since humans always want to improve our nature…

AE: One of my favourite Clearaudio ideas was the ‘Absolute Phono’ concept in 2014, which put a tiny preamplifier in the headshell itself. It seems such a great idea, why isn’t it more common?

RS: Well, technically it is a challenge, and that is giving it a higher price tag, which limits the product in terms of marketing and sales. Sometimes products are too early in the market or too late… I think here we might have been too early!

AE: Migrant waves, pandemic, the Ukraine effect – how has the company been affected by recent times?

RS: During difficult times, you need to concentrate on your core business, and to realise that in such times you need to be creative, maybe reorganise something in your organisation. This is positive, as you should never stand still.

I think we have been blessed in this regard, actually, as we see challenges as a positive; they make us stronger as a company and as a family.

AE: I couldn’t find much information on your music division – can you tell us a little about that? It’s always good to see a hi-fi company with a music division!

RS: This was originally a result of the digital CD coming onto the market in 1985. So we started around 1989 to print and press vinyl with our own label ‘clearaudio Music’, when the majors were already pushing records out of the stores. The idea was to keep them available for fans of analogue music.

AE: Well that seems to have worked well, with so many vinyl fans new and old. You must have watched the revival of vinyl in the last 15 years with delight?

RS: This is a very nice outcome for us, of course, especially as this would seem to indicate that quality will always survive. We want to keep it that way. As for the music production, we still retain this and today we are into reissues and own productions. Not on a big scale, but it’s part of our love for the music and the pleasure it brings.

Jez is the Editor of Sound+Image magazine, having inhabited that role since 2006, more or less a lustrum after departing his UK homeland to adopt an additional nationality under the more favourable climes and skies of Australia. Prior to his desertion he was Editor of the UK's Stuff magazine, and before that Editor of What Hi-Fi? magazine, and before that of the erstwhile Audiophile magazine and of Electronics Today International. He makes music as well as enjoying it, is alarmingly wedded to the notion that Led Zeppelin remains the highest point of rock'n'roll yet attained, though remains willing to assess modern pretenders. He lives in a modest shack on Sydney's Northern Beaches with his Canadian wife Deanna, a rescue greyhound called Jewels, and an assortment of changing wildlife under care. If you're seeking his articles by clicking this profile, you'll see far more of them by switching to the Australian version of WHF.