Bang & Olufsen is a name that polarises those who know it. For many, the brand is a landmark of technical and design excellence. For others, it represents style over substance.

Whatever the case, it’s hard not to be impressed by its longevity: it is 90 years old today. Few companies make it this far in the tech world, so these folks must be doing something right. To find out what that is, What Hi-Fi? visited B&O headquarters in Denmark.

The company is based in the remote Jutland town of Struer (guttural emphasis on that first ‘r’). The place is affectionately known as ‘The Farm’, although there are no barns or tractors. (There are some sheep, though, owned by a nearby farmer. Bang & Olufsen pays for them to graze nearby, because its employees like looking at them...)

The Farm is really an industrial complex comprising 12 factories, the centrepiece of which is a three-winged fortress of black rock, hardwood and glass. It’s a statement of intent and a monument to Nordic design.

Upon entering, we notice the hallway is plastered in photos – one for every employee who has spent 25 years with the company, regardless of station or seniority. There are 1231 of them, each with an engraved plaque.

It is easy to see why people stick around. Everybody seems passionate about what they do. There is an excitement here that borders on childish glee. They all speak with a tone of personal pride. Then again, this is a family business.

Early history

It all started in 1925, when engineers Peter Bang and Svend Olufsen began making radios in the attic of the Olufsen family home in Quistrup. In the early days, Olufsen’s mother sold eggs to subsidise the venture.

Get the What Hi-Fi? Newsletter

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

The pair soon found their way, and by 1927 they had their first commercially viable product. The B&O Eliminator enabled a radio to be powered by the mains, as opposed to huge batteries, which was the norm at the time. Construction had now spilled out of the attic and onto the lawn, so the business moved to a purpose-built factory in Struer. B&O has operated on that site ever since.

The 1930s saw B&O become more style-conscious, but not merely for the sake of an affectation. By now, the company’s core philosophy was emerging: to make things that are a pleasure to live with, placing equal importance on form and function.

An example is the Hyperbo (pictured, above) of 1934, a hybrid radio and gramophone with an integrated speaker, built with the styling of Bauhaus – a functionalist philosophy.

During the Second World War, B&O was active against German occupation, making radios for resistance groups, until the factory was bombed and radio supplies were cut off. The company kept going, however, turning its attention to making electric shavers. But radio production resumed in time – and soon expanded into televisions.

A 1950 prototype marked the arrival of TVs in Denmark. Back in those days, people preferred to have their sets out of sight, only bringing it out on occasion. But how do you do that, with old TVs being housed in massive wooden cabinets? The B&O solution was to add some wheels and pull-out handles, so the TV could be carted around like a wheelbarrow.

We’ll stop there with the history lesson, because 25 years is enough to make the point: this is a company compelled to fiddle. It refuses to stagnate and exists to evolve.

MORE: B&O BeoVision Avant 55 review

Quality control

Back in the present, Bang & Olufsen is keen to stress that innovation alone is not enough, and that it cares a great deal about quality. That much becomes abundantly clear as we look around several of the factories, all of which are meticulous.

Take its an aluminium plant, complete with anodising facilities, so accomplished at honing aluminium that B&O generates a healthy income just by handling the stuff for other companies.

Take its construction pits, where women - for, we're told (not for the first time on a factory tour), they are more dexterous - assemble the smallest parts and circuits before they are hauled off for testing.

Take the Torture Chamber, where assembled products are dropped, frozen, baked and smoked with hundreds of cigarettes – just to see how much abuse they can endure.

Every station is squeaky clean, with workers performing their roles at what appears to be a very leisurely pace. There’s no sign of a shouty foreman or a sweaty assembly line. Everybody takes their time and what comes out is always to specification.

MORE: B&O BeoPlay A2 review

The Cube

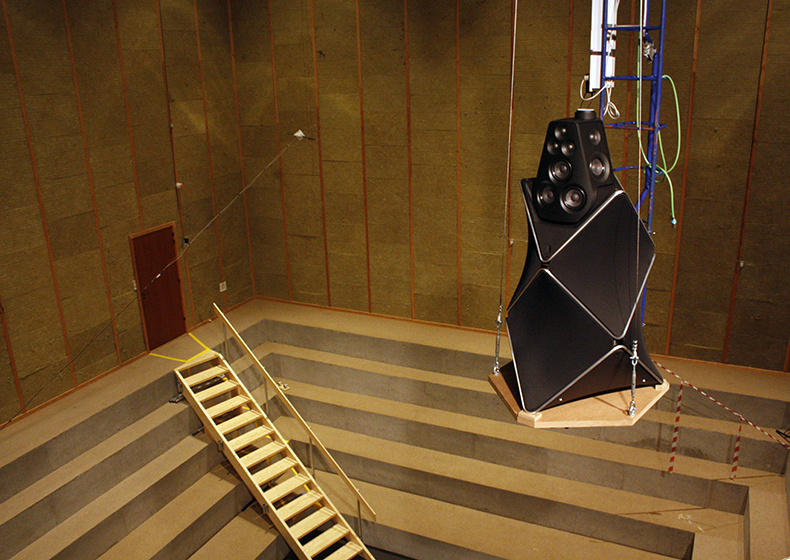

But perhaps more impressive than physical quality control is the way Bang & Olufsen approaches acoustic design. Anyone who accuses the brand of style over substance has obviously never been to ‘The Cube’, a vault deep within the building that's just for testing. It’s serious business.

It is unlike any other testing room we’ve ever seen. Many manufacturers favour anechoic (non-echo) chambers, which are lined with sound-absorbing material. But B&O doesn’t like the idea of testing in a dead room.

Instead, it just has one cavernous room – 12x12x12m – and dangles its products into the middle of it using a crane. The idea is not to absorb echoes, but to use a space so large that they cannot interfere. The reflections from the walls take so long to arrive at the measuring microphone that they can be easily ignored.

This crane/dangling approach also means the product can be rotated and measured from various angles with ease. Anything that produces sound is tested here, from speakers to televisions, which B&O calls ‘two-way speakers with large displays’.

And it’s, well, fairly safe. B&O says only one product ever fell from the crane, smashing to dust as it did so.

Once a product is measured in the Cube and all the necessary tinkering is done, it’s time for listening. B&O has weekly listening panels to assess both its own products and those of other companies under strict conditions: blind tests, using acoustically transparent curtains.

MORE: B&O BeoPlay H2 review

Meet the Tonmeister

Geoff Martin is Tonmeister of Bang & Olufsen. He’s an affable Canadian and he’s in charge of how products sound. He explains the journey from concept to production.

“Normally, it starts in the head of a visual designer. Or in the head of what we call the product definition department. These are the people who look at the market, find out what’s going on, and decide we need to make a speaker this big, with this price range, and this quality, by this date. They come to us having that plan in mind.

“We make something that is, acoustically, our best guess. We have the right-sized woofers, the right-sized tweeters, the volume in the cabinet behind the woofers is roughly the right volume. And we knew that the woofers would have different cabinets so we built a wall to keep them separate.

“Initially we won’t listen to it to find out how it sounds. The question here is if it has the power to do what we want. Can it go loud enough? Can it go low enough in frequency? We’ll also find out if the drivers will work for the size of the box. Does it have the horsepower? The next stage is usually an evolution, with different woofers and tweeters.

“We put it on the crane. That moves to the centre of the room. A computer sends a sound out, the speaker makes a funny noise, which goes into a microphone on a stick. That sound goes from the microphone back to the computer where it started. The computer looks at the difference between the sound that went out through the speaker and the one that came back through the microphone.

“Anything that’s different is caused by the speaker. We can see maybe it took out some bass or added some midrange, and we fix that by building filters in the processing. If the speaker needs more bass, we add more bass to the sound. We don’t change the physical construction of the product. Mostly, we get what we get, and we correct it in the signal processing.

“Then we look at on-axis and off-axis performance. For smaller desktop speakers, people tend to turn it on and walk away. Unless you’re in the hotspot, you won’t get the representative sound of the product. So then we change the shape. We do measurements from every angle.

“We add two correction filters – one makes it better on axis, one makes it better for the everybody else in the room – and we take it to the listening room to decide which is more important for the product. It’s a balancing act between the two. Maybe it’s 50-50. Maybe 60-40.

“I start listening. The engineer won’t tell me anything. We have a deal. He sees the measurements and he keeps all that to himself. He’ll deliver the speaker with filters to fix things, but I don’t know what’s in there. I’m blind, by choice. Because if I know where the problems are I’ll hear the problems.

“I may say, ‘there’s a problem with intermodulation and distortion at 3.6kHz’, where normal people say ‘it sounds harsh’. My job at this stage is to translate ‘harsh’ to something that’s useful for the engineer, so he can see where the problem is.

“Hopefully he’ll find what it is in the construction that causes the problem. He’ll fix it, I’ll listen, I’ll complain, he fixes it, I’ll listen, I'll complain... that goes on for days until he tells me to leave him alone.

“The final stage is the tweaking. I’ll sit in a room for two to four days, tweaking the sound. I have to do that in different rooms, because every room sounds different and you can’t change the speaker because of the room. We take it outdoors if we have to.

"At the end of the process we have five different tunings, and the engineer finds out what’s common about them. We need to see how the power response and the frequency response interact in a normal situation. We’re not looking for a flat response, like you would with studio monitors. We don’t make studio monitors, because you don’t live in studios.”

The present, the future

That process goes for the majority of acoustic designs at B&O, but the Beolab 90 is different. Not surprising, seeing as it is the company’s 90th anniversary secret weapon. This is a £26,999-per-unit design with 18 drivers, and variable beam width, and it was designed entirely with sound first.

Martin tells us that it started as his own secret project, as a sort of ‘what if’ design. In the case of the Beolab 90, his pet project got the green light and the designers had to build around the sound he designed. Geoff smiles when we mention the difficulties that the design team had in finding wood that would warp in just the right way.

He is keen to stress that this sound-entirely-first approach is abnormal for B&O, and that the usual process is a lot more of a give-and-take – but he won’t rule out the possibility of other pet projects coming to fruition.

What does the future hold? Nobody knows for sure, but it’s clear that the company prides itself on evolving and trying new things. The Beolab 90 demonstrates B&O is willing to adapt.

Already, the company has committed to a few different directions: in-car audio for the likes of Aston Martin and Audi as well as multi-room audio. There’s no model anybody can use to see what will come next, although home automation seems to be a hot topic.

Then there’s B&O Play, as opposed to Bang & Olufsen proper. It is a side branch, catering to a young, mainstream market. The company's portable speakers and headphones have a lifestyle bent to them, with an emphasis on natural materials like leather.

There is also talk of a centenary project. The company half jokes that it will take a monumental effort to out-do the Beolab 90... but that work has already begun on a Beolab 100. Nobody knows what shape that will take. Or even what it will be. Another crazy speaker? A radio? A TV? Or maybe an electric shaver? We look forward to another 10 years of Bang & Olufsen innovation and new products before we find out...

MORE: The Beolab90 is Bang & Olufsen's striking 90th anniversary speaker