A history of the strangest vinyl records ever made

From peach-scented records to those smashed up and glued back together again

There is a distorted idea that anything can be art. A cycle of misinterpretation and misrepresentation of modern art’s concepts has left an impression of the medium parodying itself – the lines between Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (the porcelain urinal that skewed boundaries a century ago) and an umbrella mislaid in a gallery have become increasingly difficult to discern.

In music, the term’s misappropriation manifests itself in anyone being labelled an artist the moment they make a sound, enforced by the judges on prime-time talent shows and singing contests. Of course music can be art, but in physical terms it can also be art beyond the music. And no other format highlights that quite like vinyl.

The history of vinyl is strewn with artistic endeavour, just as it is gimmickry and perceptibly aimless experimentation. Whatever you make of it all is (probably) up to you.

A brief history of size and speed

“The said it couldn’t be done! Hell, they said it shouldn’t be done!” If you’d bought PEABRAIN zine’s ADHD EP on release in 2014, by Saturday 29th August 2020 – the first of Record Store Day's three new drop dates – you could’ve spun it more than 3.3 million times.

Limited to 300 copies, this 2-inch EP – the smallest dedicated vinyl record we can find – contains ten-second songs from six Southampton and Portsmouth punk bands. On the face of it that could sound senseless beyond the merit of its absurdity, but plenty of bands come to mind whose songs would benefit from being truncated to a fraction of a minute.

There’s a marginally greater chance you’ll have a 5in record among your collection (or more specifically 4.7in). Back in 2007, German company Optimal Media Production developed the VinylDisc, an analogue/digital hybrid of CD and three-and-a-half-minute vinyl layer.

Its being curiosity rather than a product with hefty selling power, The Mars Volta naturally included one as a freebie for those who bought their album Bedlam In Goliath in selected US record stores in 2008 – it held a cover of Pink Floyd’s Candy And A Currant Bun on both sides, and the video for Wax Simulacra as a CD bonus.

Get the What Hi-Fi? Newsletter

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

It all becomes decidedly less experimental as you enhance the scale. Theoretically the physical size of a vinyl record, unlike tape or CD, doesn’t matter. You could hypothetically configure a setup to play a disc of any size – and, of course, the more grooves a record can house, the longer you can make it play.

This was of particular benefit to film companies for accompanying early talking pictures, and to radio for broadcasting pre-recorded programmes – both regularly used 16in discs, and perhaps even larger. Not strictly an artistic venture in itself, but interesting nonetheless.

But if you truly want to show two fingers to the art establishment, you’ll want to be tampering with rotation speed. To celebrate the third anniversary of Third Man Records in 2012, Jack White, who as you can probably guess will feature heavily in this article, threw a party at which guests were treated to The First Three Years of Blue Series Singles On One LP at 3 RPM. It held the A- and B-sides from each of the 28 “Blue Series” 7in singles the label had released to that point, and reflected White’s obsession with the number three.

Locked in the groove

By definition, all vinyl records have a size and rotation speed, and the artistry is in testing limitations or lack thereof. Similarly, there are locked grooves. Every record has one: it’s what stops the stylus dragging over the label once the music’s stopped.

Likely the best-known example of a locked groove containing music is at the end of The Beatles’ Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, creating an infinite loop and, consequently, an album you could consider being of infinite duration (the arguable existence of infinity aside).

Plenty of groups have made similar use of a locked groove, but it also holds a key to including hidden or bonus material on a vinyl record. By locking a groove before the end of a record’s running time, you can effectively hide songs from the listener that they have to lift the stylus and replace after the locked groove to hear.

Among a number of idiosyncrasies, such as the first side playing inside to out, with potentially the first-ever locked groove on the outside of a record, and others we’ll mention a little later on in this piece, the ULTRA version of Jack White’s 2014 solo record Lazaretto went a step further than hiding tracks in locked grooves, secreting two under the centre labels. Even more obstinately, one plays at 45rpm and the other at 78rpm, creating what the label believes to be the first three-speed LP.

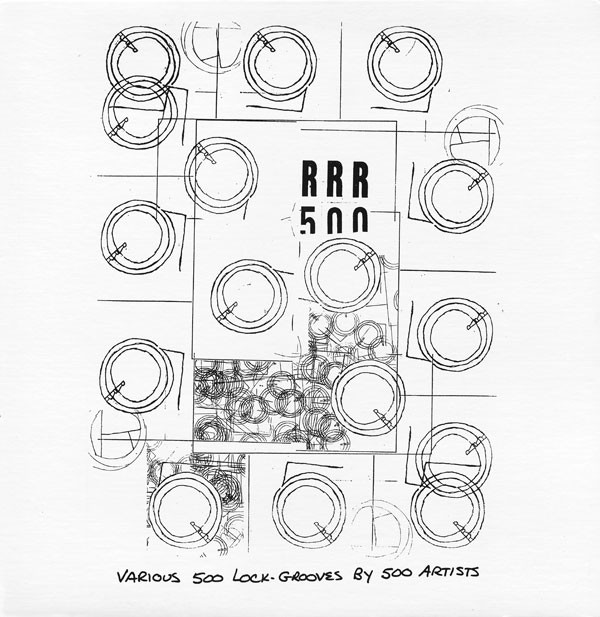

Going a step further, in 1998 American label RRRecords released RRR500, a compilation of 500 locked grooves sourced from 500 artists as diverse Charlie Parker, Sonic Youth and The Teletubbies. Pointless? Perhaps, though similar compilations of locked grooves have proven useful for early sound effects or DJs building dance tracks in real time. (Context seems continually here to provide a slender line between practicality and pure gubbins.)

But what if it were up to chance rather than the listener’s will as to which tracks a record played? In 1973, side two of Monty Python’s fourth comedy album, The Monty Python Matching Tie and Handkerchief, was cut with parallel grooves – different tracks will play depending on which groove the stylus is originally placed. To further confuse the audience, neither side of the original copies were marked as to which was A and which was B, and there was no track listing: a two-sided record with three sides of material, and who knows what you were about to hear?

We aren’t certain Monty Python were the absolute pioneers of using parallel grooves in such a fashion, and certainly musicians have adopted them since to add alternative beginnings or endings to their songs (see White’s ULTRA version of Lazaretto again, which has acoustic and electric intros to side-two opener Just One Drink running parallel before joining to play the body of the song), but we can be fairly positive Janek Schaefer was first to his particular kind of truly random-playing LP. The award-winning English composer’s 2003 release, Skate, comprised several lengths of groove marooned by blank vinyl, meaning the stylus would skate and skip between grooves free from the physical shackles of pre-determination.

Still, it isn’t far beyond the realms of possibility Schaefer was inspired in his invention by experimental Czech artist Milan Knizak. Member of a multidisciplinary, anti-artistic community known as Fluxus, Knizak has this to say of his sonic endeavours of the 60s: “[In the early 60s] I used to play records both too slowly and too fast, thereby creating new compositions. In 1965 I started to destroy records: scratch them, punch holes in them, break them. By playing them over and over again, which destroyed the needle and often the record player too, an entirely new music was created: unexpected, nerve-racking and aggressive.

“I developed this system further. I began sticking tape on top of records, painting over them, burning them, cutting them up and gluing different parts of records back together to achieve the widest possible variety of sounds. Since music that results from playing ruined gramophone records cannot be transcribed to notes, the records themselves may be considered as notations at the same time.”

Schaefer wasn't the first to be influenced – works such as Arthur Kopke’s Music While You Work, Piece #1 adorned spots of glue and tape to similarly redirect the stylus. We’re desperately unlikely to find any of Knizak’s pioneering works while crate-digging, but doesn’t it give you a new appreciation of the dinks and scratches on your overplayed pet vinyl?

New material, new material

What’s vinyl when it isn’t vinyl? Well, escaping its literal definition for a moment, it could be pretty much anything. In 1903, long before even shellac was usurped as the record album’s most common base material, chocolatier Stollwerk created a player that reproduced music etched in grooves in chocolate. More than a century later, in 2012, French electro producer Breakbot released a special edition chocolate version of his record By Your Side, making his fans’ music taste tangible if nothing else.

There’ve been plenty subsequent experimentations in the LP’s physical makeup since Stollwerk’s turn-of-the-century innovation, including wood, glass, sandpaper and, extraordinarily, ice. Novelties all, but few can claim to have fashioned a creation so offbeat or inspired as that of the Kingdom of Bhutan. In 1973, the South Asian nation issued a number of postage stamps that doubled as miniature phonograph records, playing traditional folk songs and tourist board messages. Apparently originally scorned by stamp collectors – an episode of Bhutanese Points of View to which we’d really like to find the tape – they’re now, unsurprisingly, worth a pretty penny to stamp- and record-collectors alike.

In the post-war Soviet Union, however, it wasn’t artists or public relations experts who were the source of such sonic innovation, but bootleggers. In rebellion against the nation’s severe prohibition of Western music and indeed culture on a greater scale throughout the 1950s and 1960s, particularly jazz and rock ‘n’ roll, began roentgenizdat: ‘bone music’. Etched into x-rays, songs such as Rock Around The Clock and Boogie-Woogie Bugle Boy were made available (though predictably of inferior sonic quality to the original) to Eastern Europeans who could keep a secret.

Illustrating the mainstream appeal of vinyl in 2019, and combining two aged formats in one, was Hallmark's Valentine's Day card and vinyl offering. Each slice of dead tree came complete with a 7in vinyl record for your loved one, and there was even a choice of seven different versions. Sadly, all opted for rather unattractive track selections (though of course beauty, sonic or otherwise, is in the eye of the beholder).

Of course you can’t make a record out of literally anything . Even Jack White will struggle to etch the grooves of any forthcoming Third Man release into memories, crime or customer service – but what about grief? And Vinyly is a company that presses records from your loved-ones’ ashes, allowing you to turn your gran into a grime mix tape or have your cat forever play its final meow. In certain circles, it would seem, vinyl is very much dead.

But for those curmudgeons who daren’t stray so far from the beaten path, there’s still experimentation to be had when it comes to traditional vinyl. Largely, that means filling it. Unsurprisingly, Third Man has tampered with many a record in this way. Undeterred by Disney’s leaky failure at producing a liquid-filled disc when releasing the soundtrack to The Black Hole in 1979, Jack White succeeded 33 years later (given his track record we’re coy to put that down to mere coincidence) with the 12-inch single of Sixteen Saltines.

And when Third Man released The Dead Weather’s Blue Blood Blues single two years earlier, it encased a 7in record within the main 12in. As such, to hear the fourth and fifth tracks you’d have to break the smaller disc from its parent, cracking it through the middle and effectively destroying the main single. “It’s one of the many mind games we like to play with you here at Third Man Records,” says White, and one that’s worth upwards of £450 if you’re currently flogging one on Discogs.

Chickenfeed, however, when you compare it to the $2,500 you’d have had to spend to land one of ten special editions of The Flaming Lips and Heady Fwends, released for Record Store Day in 2012. That’s because for this particular edition of the collaborative album, Wayne Coyne collected vials of blood from artists involved and pressed them into the vinyl. It’s a fairly heady list of donors, including Nick Cave, Erykah Badu, Bon Iver’s Justin Vernon, Sean Lennon and Coldplay’s Chris Martin.

With the blueprint solidly set, artists have sandwiched everything from string to autumn leaves and rose petals into their vinyl. Among those worthy of particular mention are Emperor Yes’s An Island Called Earth (meteorite dust), Bobby Darin’s autograph in The Bobby Darin Story, and ash from a scorched copy of the Bible in the gloriously brazen and blasphemously named Hellmouth’s Gravestone Skyline. Perhaps the most striking, though, is the run of 100 copies of Euhippus’s Getting Your Hair Wet With Pee, which contained hair pressed indiscreetly into translucent yellow vinyl.

You’re likely also to have come across artwork etched onto discs, either in blank vinyl or laser etched onto sides so they remain playable, but there’re some artists who’ve gone a step further to hide visual works on or in their LPs. To hark back to the ULTRA edition Lazaretto once again, in the dead wax on side one of the record artist Tristan Duke hand-etched a floating hologram of an angel that revolves as the record spins. That was the first time such a trick had been done, but was later aped by Disney for their release of the Star Wars: The Force Awakens soundtrack, this time with a Millennium Falcon and TIE Fighter.

Further visual trickery can be found in the form of zoetrope. Such spinning animations, where movement is implied when focusing on a specific point, were popularised more than a century-and-a-half ago, but the rise of the picture disc has breathed into it new life in vinyl form. For Record Store Day in 2013, for example, Kate Bush released a reworking of Running Up That Hill (A Deal With God) on which ran a suitably toned athlete with a fishes head, while Animal Collective were so kind as to give away a turntable mat with zoetrope design along with their 2016 LP Painting With.

Now it’s unusual to reach this stage of an article about musical innovation before the first mention of David Bowie, but rest assured this isn’t to be the final mention of his last LP Blackstar. With designer Jonathan Barnbrook refusing to reveal his hand concerning all he concealed in the vinyl version of the album – “Remember what Bowie said about not explaining everything,” he told Mary Anne Hobbs – it took fans four months to discover that, when exposed to sunlight, the disc reveals the image of a galaxy. Half a year later, SPIN reported its readers’ finds of reflections cast by the record when held to light at an angle: on one side a star and on the other a space ship.

While not strictly built into the record, Warp records went a step further when they developed an augmented reality iOS app that melds analogue and digital to reveal cityscapes as you play vinyl copies of Brian Eno and Karl Hyde’s collaborative album Someday World. “After downloading the app, fans can use their iOS device to watch and explore as new ‘outsider architecture’ metropolises spring into life around their vinyl copy of the album,” says Warp. That’s inarguably immersive listening.

Covers, labels and nauseating turntables

‘Cover art’ would seem to be an inescapable collective term that seeks to tar all sleeves with the same unwavering definition, but there are some that elevate themselves to a level above the crowd. In many ways the most iconic example of cover art folklore concerns Factory Records’ 1983 release of New Order’s Blue Monday.

It remains the biggest selling 12in single of all time, but Peter Saville’s design (a die-cut sleeve resembling a floppy disc) is rumoured to have cost more for Factory to produce than it did for listeners to buy, to the tune of 5p per copy. Production methods were simplified for later presses, leaving it ambiguous as to whether the world’s best-selling 12in single finally lost money, turned a profit or broke even, but it’s unlikely the label ever again underestimated a release to such a degree. (We spoke to Geoff Pesche, the man who cut Blue Monday at Abbey Road Studios, if you want to get his side of the story.)

Again, film soundtracks are apt to make this list. Firstly Gremlins, whose vinyl edition urged fans to do precisely what the film had taught them not to when handling Mogwai. Exposing the cover to bright light reveals hidden messages, while wetting either sleeve of the double LP set will uncover extra drawings.

Not satisfied with extra visuals, when Ecto Containment System released the Ghostbusters vinyl in 2014, they appealed to the touch and smell of the film’s following: the cover was the texture of, and scented like, a marshmallow (though listeners were warned against trying to taste it). Don’t imagine Third Man allowed Ghostbusters to be first to get up fans’ noses, of course – for the 2010 release of Karen Elson’s EP The Ghost Who Walks, the disc itself was peach-scented.

Bowie disciples have seemingly made a full-time job of exploring Blackstar’s locked secrets, and there’s further intrigue surrounding the LP’s cover. One fan discovered that holding it under blacklight turns the usually white sections of the cover a kind of neon blue while, rather more romantically, another found that – at an angle – the inner sections of the gatefold sleeve reflect upon each other to give the impression of Bowie observing a galaxy from his window. It’s unconfirmed whether the latter trait was included purposefully, but we like the poetic image it creates nonetheless.

Not exactly hidden, given that the EP was sold with glasses specifically for the trick, but the sleeve of Ty Segall’s Mr Face EP was designed as a 3D image. It being a double 7in, you could also hold both discs to your face, one translucent red and one translucent blue, to use them as (likely) the first musical 3D glasses. We’d consider that marginally less gimmicky than the sleeves of Wanda Jackson’s Third-Man-conceived release of The Party Ain’t Over, a musical greetings card that plays a snippet of the opening track when opened, or Lemon Jelly’s Soft Rock, made from Levi jeans and complete with a condom nestling in the pocket.

But do you even need a sleeve? In 1985, Christian Marclay released Record Without A Cover, designed specifically to become war-torn and subsequently unique. In 2012, Nik Colk Void released her Gold E 7in along similar conceptual lines, though less reminiscent of the Emperor’s new clothes: hers was a cover made of playable degradable polyurethane plastic that reacted with the vinyl to change its sound over time.

And there’s no reason centre labels should be neglected in the name of artistic exploration. On the heels of his hidden tracks to be played through the paper of Lazaretto, when Jack White released High Ball Stepper as one of the album’s singles he made the label with a rather lavish velveteen finish.

Not quite as impressive as the artistic license taken by The Stranglers on the centre label of their first EP, Something Better Change/Straighten Out, however. Side one exhibited a rather psychedelic depiction of the band, with the sleeve notes tempting discerning punks to experiment playing the record a little faster than they would a usual 7in. “This EP has a special label,” it read. “Viewing the label while the record is revolving may result in slight dizziness (especially if record is rotated at speeds in excess of 78rpm).”

Whether these be art, gimmick or merely the product of musicians with too much time and too well stocked a medicine cabinet, we’ll leave you to decide. Meanwhile, we’ve been tempted to listen to The Stranglers and make ourselves sick.