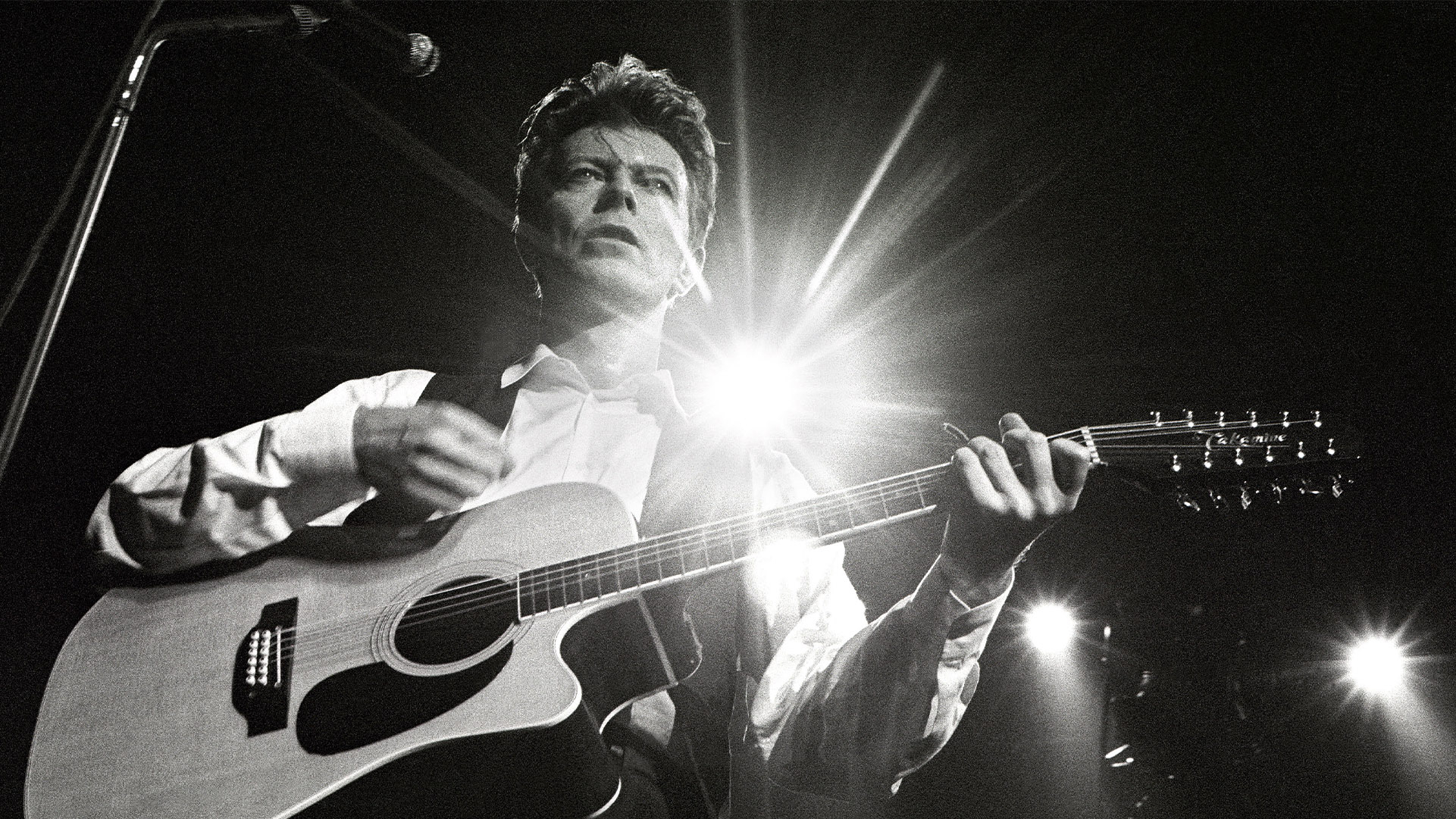

12 of the best David Bowie songs to test your hi-fi system

Fifty years of extraordinary art-rock

The man called ‘David Bowie’ was a recording artist between 1966 and 2016; Brixton’s David Jones tried and failed to have a hit single for a few years before he changed his name, and it would be the early 70s before he achieved anything approaching success. After that, though, the dam broke, and Bowie became a) the world’s premier gender-bending art-rocker, b) an inspiration to any number of subsequent musicians, c) a composer and performer of several genre-defying singles and albums, and d) shorthand for the sort of combination of ‘commercial appeal’ and ‘artistic integrity’ that most recording artists would conceivably kill for.

And on top of that, he was always profoundly concerned with the sound, and the texture, and the colour of his recordings, a fiend for an unusual arrangement, and extremely judicious in the people he chose to collaborate with – especially studio personnel. All of which makes many of his recordings excellent for revealing the secrets of the system that’s playing them.

Picking the dozen ‘best’ recordings from a career as long and varied as David Bowie’s is not only an exercise in futility, it’s a sure-fire way to start arguments and ruin friendships. So instead we have picked 12 tracks that will really let your headphones or speaker system show you what they’re made of.

The Bewlay Brothers (Hunky Dory, 1971)

Close-mic’d acoustic guitar, front-line vocal that’s considerably closer-mic’d than that, and some oddly treated organ and bass form the basis of the deeply unsettling closing track from the 1971 album that almost, but not quite, brought Bowie to mainstream attention. The gentle ebb and flow of the arrangement and its instrumentation are a proper appraisal of a system’s ability to track minor harmonic variations, and the moments of attack (“oh, and we were gone”) test dynamic potency too.

Most of all, though, this recording will give your system’s midrange resolution a thorough examination thanks to the occasional vocal double-tracking, the odd voice effects and background vocal lines – and that’s before you get to the “please come away” coda that sounds like a playground game in the most sinister primary school imaginable.

Lady Stardust (The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, 1972)

Bowie may have created a character of mascara'd androgyny who had apparently fallen to Earth in order to preach kinky sex and glam-rock redemption, but at no point during the course of the Ziggy Stardust album did he take his eye off the ball. The songs, without exception, are bullet-proof juggernauts – and even when, as with Lady Stardust, they are tenderly contemplative, they still feature hooks strong enough to hang an elephant off.

Get the What Hi-Fi? Newsletter

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

This tune will test low-frequency speed and tonal variation, soundstaging, midrange fidelity (of course) – and when the chorus (which is robust enough to have been a football terrace anthem in another life) kicks in, stereo focus, separation and dynamic headroom all get a workout too.

Buy The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars on Amazon

Cracked Actor (Aladdin Sane, 1973)

If you like your crunch and grind as crunchy and grind-y as possible, you have come to the right place. This extraordinarily libidinous cut from Aladdin Sane (a lad insane, geddit?) manages to out-Stones the Rolling Stones while remaining only and utterly a David Bowie recording, from the arch vocal delivery to the remarkable aggression and feedback of Mick Ronson’s guitar. If your system can’t fully describe the overdrive of the guitar sound, the almost tangible dirt under its fingernails, Cracked Actor loses a stack of its attitude – and on top of that, there’s low-frequency speed and momentum to be maintained too.

Soundstaging needs to be sufficient to make the whole piece hang together as a singular performance, and midrange projection must allow the squealing harmonica some space in which to do its thing – even though it sounds like it’s barely keeping its head above the swampy, murky water.

Stay (Station to Station, 1976)

During the couple of years Bowie spent in Los Angeles he developed a) an epic cocaine habit, and b) a theory of ‘the squashed remains of ethnic music… written and sung by a white Limey’. Both in equal measure inform Stay, a sweeping, warped dancefloor-friendly powerhouse of heroic ambition performed by a team of crack musicians. Rhythmic expression and positivity are key here, so control and intensity of both the low frequencies and percussive sounds at the opposite end of the range must be keen.

The midrange here is mostly a scrap between desert-dry rhythm guitar, abrasive lead guitar and double-tracked vocal – only decent separation and focus will prevent them from collapsing in on themselves. And unless your system is capable of creating a convincing sense of scale, the breadth of the arrangement will lose a ton of impact.

Buy Station to Station on Amazon

Always Crashing in the Same Car (Low, 1977)

Newly enchanted with the idea of ‘European Man’ in general and the exciting new sounds of Germany in particular, Bowie decamped to Berlin, hooked up with Brian Eno (as well as long-time producer Tony Visconti) and created some of his most innovative, progressive music so far. The squalling, chilly, heavily treated sound of Low in general and Always Crashing in the Same Car in particular will severely test a system’s tonal response – especially the treatment on the drum kit, which came courtesy of an Eventide H910 Harmoniser which, according to Visconti, “fucks with the fabric of time”.

The processed electronic sounds involved in this recording demand that your set-up is able to describe attack and decay with certainty, as well as being alert to the harmonic variations that are apparent throughout.

Beauty and the Beast (“Heroes”, 1977)

In some ways, Beauty and the Beast is recognisable as pop music – it follows the verse/chorus/middle eight/chorus template pretty closely, after all. But then you realise that in 1977, no one else’s pop music sounded remotely like this – the brutality of the sound, the alienation and disconnect that’s tangible in the vocal performance, the overall sense of otherness.

So what, in all honesty, is your system supposed to do with it? Well, there’s the backing vocal to be spotlit and its attitude to be revealed, the tacky tonality of the piano to be expressed, the gimpy rhythm to be gripped and subdued – and that, really, is just for starters. This is a recording that is seemingly determined to shake itself to pieces, and it’s up to your set-up to hold it all together.

Fashion (Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps), 1980)

By now, Bowie’s influence is such that any number of imitators are slapping on the make-up, demanding increasingly outlandish hairdos and adopting outrageous ‘gor blimey missus’ London inflections in their singing voices – but not one of them has a hint of his star-power, of course. It’s a state of affairs made only too plain by Fashion, an effortlessly classy slice of funk-rock punctuated by a Robert Fripp guitar line that sounds like animals fighting.

The production is widescreen and complex, with a great many transient details to be revealed by your system – or ignored, if your system’s not up to it. The sinuous bassline is strongly opposed to the terse midrange punctuations, and if it’s going to glide as it should then your set-up has to have iron-fisted control of the lowest frequencies.

Buy Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) on Amazon

Absolute Beginners (Absolute Beginners OST, 1986)

The 80s were not exactly kind to David Bowie – he spent too much time second-guessing himself and worrying about how best to repay the absolutely enormous advance paid to him by new record label EMI America, and consequently, inspiration was at a premium. But when the pressure was off, as it was when composing the main theme to a film in which he was only too glad to accept a role, he remained capable of transcendence.

A 60s-inflected slice of big-chorus pop music, Absolute Beginners rides on a bed of tambourine and piano – but the terse saxophone inputs need to be delivered with all their punch and blare intact, just as surely as your system needs to deliver all that character and attitude in the vocal harmonies. And the 114bpm tempo should just roll.

Buy Absolute Beginners OST on Amazon

Hallo Spaceboy (1. Outside (The Nathan Adler Diaries: A Hyper-Cycle), 1995)

“You’re released but your custody calls” – having finally emerged from a decade-long struggle for relevance, David Bowie launched a comeback with all arty-farty guns blazing. Co-opting the punishing industrial sounds of the likes of Nine Inch Nails and taking some inspiration from David Lynch’s Twin Peaks, the 1. Outside album sounded like a blast furnace – and Hello Spaceboy was where its metallic attack combined with certainty of vision most effectively.

What’s your system’s tonality like? Can it handle the pounding, the noise, the grating and droning? And most of all, what’s it like at teasing out the details from the depths of a foggy, opaque mix? If the answer to these questions is “not much cop”, this recording is going to sound like nothing more than a motorway pile-up.

Buy 1. Outside (The Nathan Adler Diaries: A Hyper-Cycle) on Amazon

Seven Years in Tibet (Earthling, 1997)

There was more than a hint of the ‘trendy uncle at a wedding reception’ in the drum’n’bass inflections of Earthling, but despite the over-earnestness, the album contains some of Bowie’s strongest writing in years. Seven Years in Tibet is – as a trendy uncle might say – an absolute banger, combining a great arrangement, a bomb-proof melody and a tangible sense of commitment. Ideally, it should be reproduced by a system with good insight and decent powers of detail retrieval, one that’s able to keep a close eye on the more minor events at the edges of the soundstage.

This is a recording that is built from a lot of very disparate sounds, so your set-up will need to be able to unify it into a single piece – because otherwise, it could easily sound like a lot of discrete occurrences.

I Would Be Your Slave (Heathen, 2002)

There aren’t all that many outright love songs in David Bowie’s body of work – but here’s one, and what a humble, vulnerable and heartfelt love song it is. There’s a delicacy and tenderness to I Would Be Your Slave that’s strongly at odds with the power-packed muscularity of his output from the previous few years – which means your system needs to exhibit deftness, manoeuvrability and a lightness of touch to allow the exposed and unguarded nature of the recording full expression.

Midrange resolution in particular gets a thorough examination here, and the gentle dynamic variations in tone and texture need identifying if the song’s not going to sound rather one-note and expressionless. This is a late(r)-period gem, and deserves to be heard as such.

★ (Blackstar, 2016)

He knew he was dying, of course, and with hindsight it’s obvious he intended to go out with his boots on. ★ is a restless, rich and thoroughly strange recording, ambiguous in a very deliberate way – nothing Bowie had recorded in the 21st century had prepared anyone for just how determinedly peculiar this song (and the album from which it’s taken) is.

And just as it’s difficult, even now, to get your head around, it will put your set-up through the wringer in every respect. Tonal and textural variation, big dynamic upheavals, flinching electronics and strident jazz-inflected horns, a stage that’s full to bursting and a mix that delights in throwing wrong turns at the listener… there is no such thing as a full-system workout in a single song, of course, but this comes a lot closer than most.

MORE:

Our playlist of the best British rock songs to test your system

Prefer The Beatles? Here are the best songs from The Beatles

Or kick back with our list of the best Pink Floyd songs to test your hi-fi system

Simon Lucas is a freelance technology journalist and consultant, with particular emphasis on the audio/video aspects of home entertainment. Before embracing the carefree life of the freelancer, he was editor of What Hi-Fi? – since then, he's written for titles such as GQ, Metro, The Guardian and Stuff, among many others.

-

Jasonovich Ok name the Bowie songReply

We are the goon squad and we're coming to townBeep-beepBeep-beep