13 heroic tech failures, from Betamax to HD DVD

We wax lyrical on the failure of 3D TV, why the Amazon Fire Phone went up in flames and more

Since the very first issue of What Hi-Fi? was published in 1976, we have covered numerous technological advances in the world of hi-fi and home entertainment.

Many have stood the test of time – some, like vinyl, have come back from what looked certain to be the grave – but a combination of flawed concepts, poor timing or costly format wars (or all three) have seen others rendered obsolete.

Here we revisit some of the tech once hailed as the future of home entertainment – and take comfort in the knowledge none of these innovations is in the running for a gong at our upcoming 39th What Hi-Fi? Awards ceremony...

Amazon Fire Phone

2014 - 2015

Ah, the forgotten Fire – the doomed Jeff Bezos device few people remember even existed. It was announced on 18th June, 2014, hot on the heels of the smash-hit 2013 Kindle Fire HDX 7 and marked Amazon's first (and as it turned out, only) foray into 3D-enabled Fire smartphone propositions.

Early user-feedback kicked the Fire Phone for its launch pricing – which, at $299 for the 64GB model with a two-year contract (or $749 without one) was too rich for the blood of most cash-savvy Amazon fans – drab design and gimmicky features, particularly Dynamic Perspective, which was labelled distracting at best and worthless at worst. And because Amazon didn't offer the same seamless range of services or variety of apps as Apple, the ecosystem was also a let down.

Three weeks post-launch, the Guardian did some number crunching and reported that although Amazon remained stoically silent about its figures, no more than 35,000 Fire Phones could have been sold.

Get the What Hi-Fi? Newsletter

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

Amazon extinguished that particular Fire barely a year after starting it and accepted a loss reportedly in the region of $170m. Still, if Bezos merrily launching himself into space is anything to go on, the firm managed to absorb it.

- See our pick of the best smartphones 2021: best phones for music and movies on the move

3D TV

2010 - 2017

Why did 3D TV fail? It was all going so well: CES 2010 saw the exciting launch of 3D home TV propositions from celebrated brands Sony and Panasonic – and we'd all just come home from watching Avatar in glorious 3D at the cinema. Now you could have that at home? Winning.

Only, 3D TV didn't win viewers over long-term. Although sales of 3D TVs peaked at 41.5m units in 2012 (as reported by DisplaySearch), a combination of extra costs and bad timing saw sales decline significantly from 2013 onwards. 4K resolution, which could have made the quality of 3D much better while still using passive agnostic glasses, was still in its infancy and yet to become anywhere near affordable enough to get involved, while the active specs available were expensive, not universally compatible with competing technologies, needed constant charging and often felt uncomfortable (or got chewed by the dog).

Since early 2017, almost all 3D TVs and services have joined the bleedin' choir invisible. Samsung hasn't made a 3D TV since 2015 – not even in its most expensive flagship lines. But 3D visuals aren't pushing up the daisies just yet. For one thing, you can now visit the world's first 10K 3D planetarium near Calais, featuring 12 top Sony SXRD projectors in an old WWII rocket base. France is now off the amber plus list for arrivals from the UK, after all...

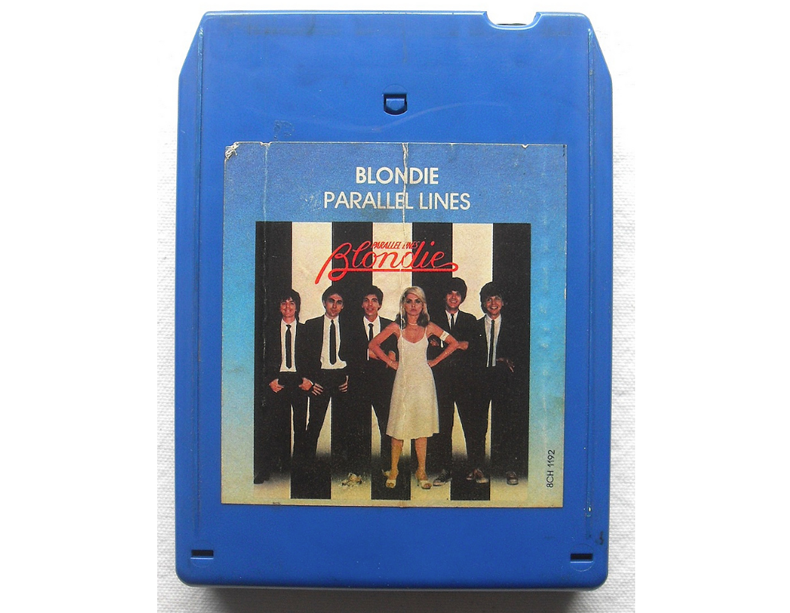

8-track cartridge

1965 - 1982

The first magnetic tape recorders became available as long ago as 1940, but they were bulky, complicated and expensive. Attempts to finesse the open-reel format into cartridges (to reduce complexity and vulnerability) began almost as soon as the reel-to-reel standard was perfected, and by 1965 a giddily high-powered consortium of RCA, Ford, Ampex and Lear (among others) had perfected 8-track tape. It was the simplest and most durable magnetic tape configuration to date, and with the longest playback time to boot.

The motor industry loved 8-track – Bentley and Rolls Royce fitted them as standard for years – and for a while it looked like it might have the fidelity to become a home standard as well as a convenience for the car. But Philips had been refining its compact cassette format since its introduction in 1962, and by the early 70s improvements in sound quality and durability saw the more portable alternative overhaul 8-track.

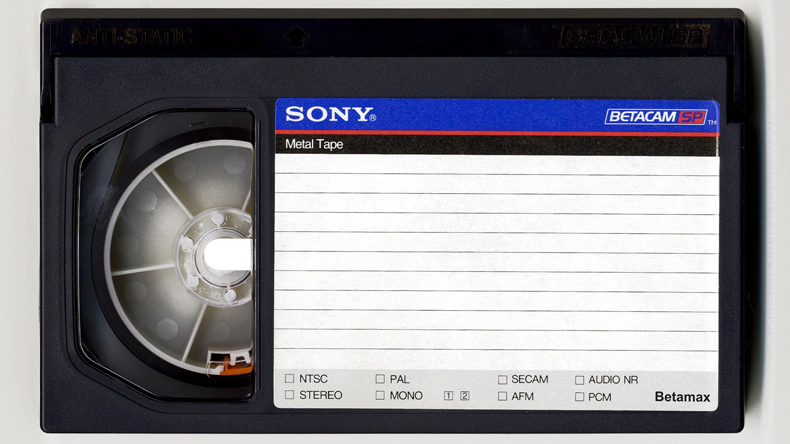

Betamax

1975 - 2002

If there's one lesson to be learned from the demise of Betamax, it's ‘never second-guess consumers’. However, the even more important lesson, 'don’t indulge in protracted and public format wars’ is one the consumer electronics industry seems incapable of learning. Sony’s Betamax videotape recording standard – which briefly held a 100 per cent market share, until JVC’s VHS format launched the following year – was widely recognised as the best-performing home recording format. But consumers didn’t want ‘better’ anything like as much as they wanted ‘cheaper’.

As the more affordable VHS format, which also had a significant advantage over Betamax in recording times, gained ground in North America, economies of scale meant VHS equipment was more affordable in Europe than Betamax. Sony read the runes as early as 1988, when it began producing its own VHS hardware, but – in what was a demonstration of either admirable customer service or weapons-grade stubbornness – continued production of Betamax machines until 2002 and Betamax cassettes until 2015.

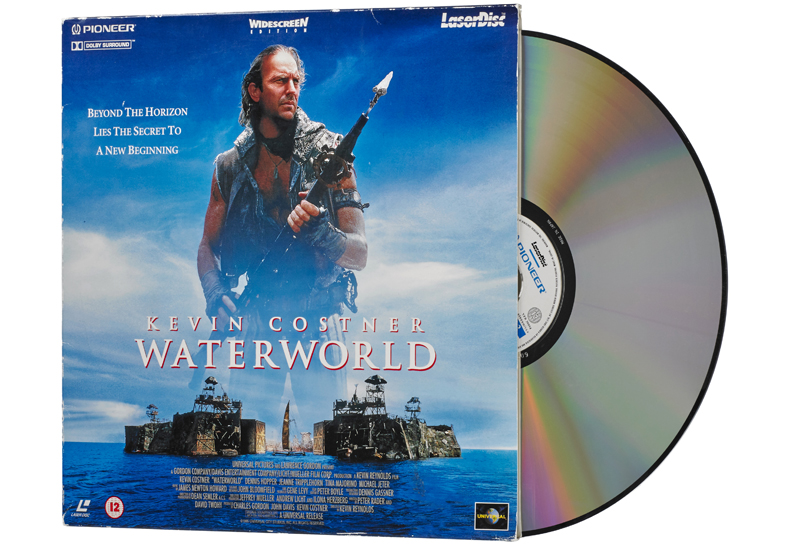

LaserDisc

1978 - 1996

LaserDisc may not have lasted the distance, but it can be credited with paving the way for the global success of Compact Disc, DVD and Blu-ray – its concepts and technologies informed all later optical disc formats. Developed in the early 70s by Philips and MCA (the latter of which marketed it in North America as DiscoVision), the format first hit the shelves in 1978, just a couple of years after VHS. By 1980 it had been sold to Pioneer, who badged it as both LaserDisc and LaserVision.

There was no disputing the superior quality of LaserDisc’s audio and video over VHS – it featured 440 horizontal lines compared to the 240 of VHS. But, crucially, it was a read-only format with no facility for recording. Almost as crucially, the discs themselves were 12 inches in diameter, the same size as vinyl LPs. They looked anachronistic next to a tidy little VHS or Betamax cassette, and by the turn of the century it was all over.

Video 2000

1979 - 1988

Video 2000 (also known as V2000, Video Compact Cassette or VCC) was the result of collaboration between Philips and Grundig. Aimed at challenging the fledgling VHS and Betamax home video recording standards, the lack of a catchy and definitive moniker was not the only reason the technology floundered.

V2000 was innovative compared to its rivals, notably in the recording times of its two-sided cassettes. But it arrived after both VHS and Betamax, entering a market already wary of competing formats, and it wasn't marketed in North America at all. There was no camcorder and, crucially, no suggestion that the pornography industry was interested in V2000. And thus it was discontinued, years after the public had forgotten all about it.

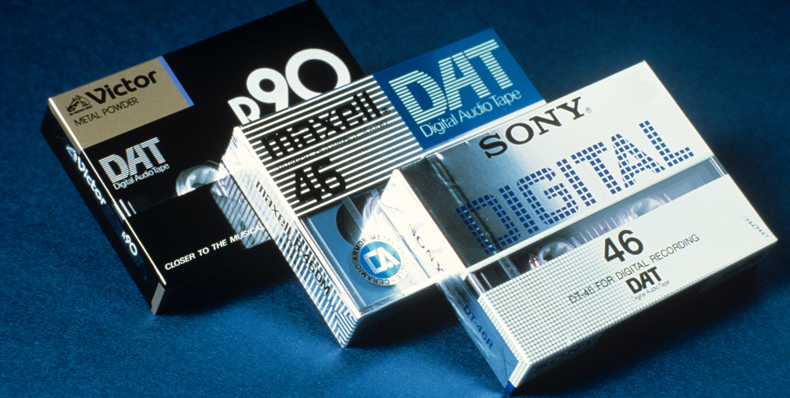

DAT

1987 - 2005

Technologically, Sony’s first stab at overhauling the ubiquitous compact cassette as the default recording medium was a brilliant success. By all other important metrics, though, digital audio tape died on its arse.

Roughly half the size of a compact cassette, DAT used 4mm magnetic tape to record, digitally and losslessly, at a better-than-CD resolution of 16bit/48kHz. This caused paroxysms throughout the music industry – the Recording Industry Association of America threatened legal action.

The vagaries of the global money markets meant DAT was more expensive than Sony had intended (close to $1000 for a player/recorder, double what had been envisaged) and consumers were, at best, unconvinced. Thanks to its high quality performance, DAT found favour as a professional medium in recording and TV studios. But as a consumer technology, it’s a footnote – and something of a missed opportunity.

CDi

1991 - 1998

Compact Disc Interactive was an attempt by the ever-intrepid Philips to produce a disc-based system with greater flexibility and functionality than either audio CD players or games consoles. At launch it cost around $700, considerably cheaper than contemporary PCs. Then again, it did come without keyboard, monitor and hard- or floppy drives.

Although far more ambitious than a simple games console – it could play audio-, photo- and video-CDs as well as games, and was available with a slew of educational and reference titles at a time when internet access was far from common – CDi struggled to shake off its public perception as a games console.

Pretty quickly the public also perceived it to be a failure. Despite support from brands as varied as Bang & Olufsen, Grundig and LG, grumbles about the quality of graphics, controls and, most damningly, stability finished CDi in short order.

DCC

1992 - 1996

How do you replace a technology that’s been a runaway success and achieved levels of ubiquity you wouldn’t have dared hope for? Well, if you’re Philips and the technology in question is compact cassette, the answer is with more of the same, only (ta-dah!) digital. A joint venture between Philips and Matsushita, digital compact cassette was, visually at least, very similar to the analogue cassette it sought to supersede.

Analogue cassettes could be played on DCC recorders and this backward compatibility meant a way into digital recording without sacrificing existing cassette collections. But with DCC vying with MiniDisc (and, to a lesser extent, DAT) for market share, customers were cautious. When the dust settled, DCC proved to have little staying power and Philips quietly buried the format in 1996.

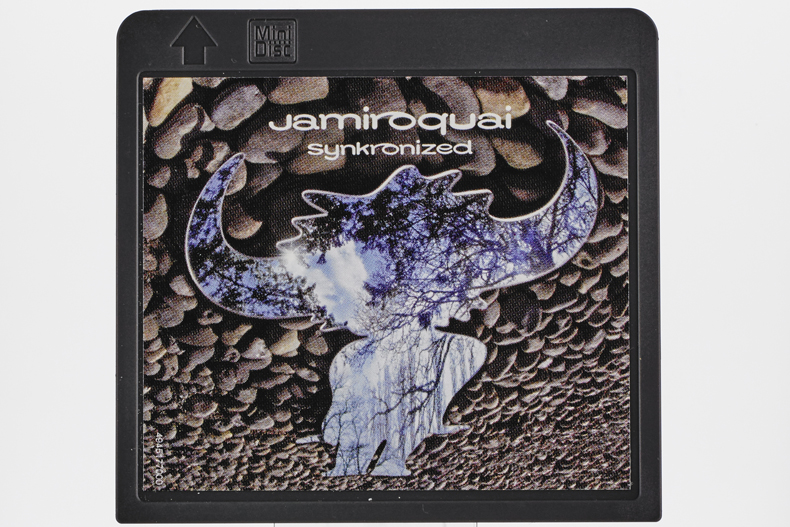

MiniDisc

1992 - 2013

Having seen its plans for DAT to be an affordable hi-tech replacement for compact cassette scuppered by international money markets and industry outrage, Sony regrouped and served up MiniDisc in 1992. In the pre-MP3 era, the MD was futuristically small (just 68 x 72 x 5mm) and its 80-minute storage capacity exactly the same as the bigger, less portable CD-R. For a little while it seemed to be the natural successor to Sony’s ubiquitous Walkman series of portable cassette players.

There was scant enthusiasm from record companies, though, who were suspicious of MiniDisc’s purportedly high-quality recording capabilities (although there was nothing like the uproar that surrounded DAT). Pre-recorded albums were scarce, there were a slew of copyright protection initiatives, and by 1998 the first MP3 players had reached the market. Not even offering a trade-off between sound quality and longer recording times (320 minutes at sea-bed compression levels) could save MiniDisc.

Sony can be pretty bloody-minded where its formats are concerned though, and shipment of MD devices didn’t end until 2013. In reality, it had been dead in the water since the turn of the century.

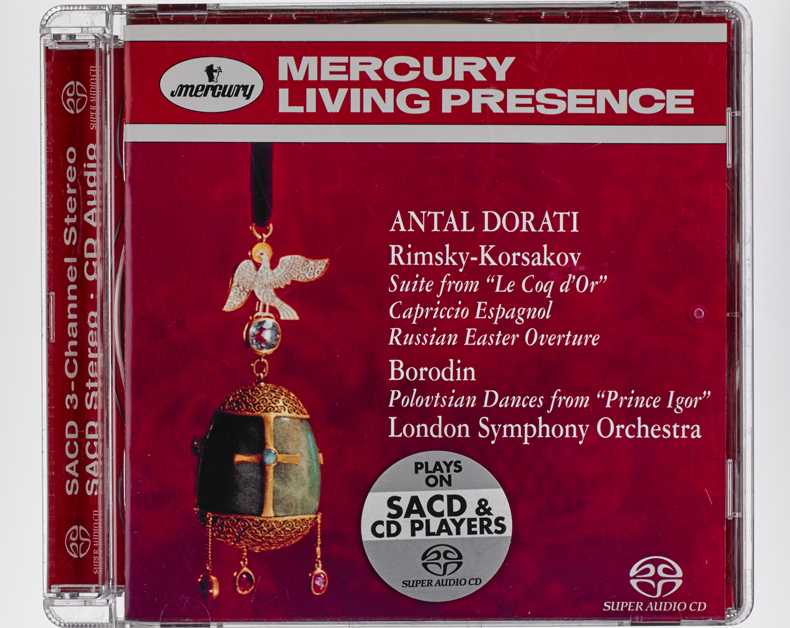

SACD

1999 - 2007

Flushed with pride at the success of their jointly developed Compact Disc format, Sony and Phillips put their heads together again to introduce high-resolution audio to the masses. Super Audio CD was physically identical to CD, but software support was slow to materialise (inexplicable when you consider Sony owned – and still continues to own – the huge CBS Records catalogue). And while hybrid SACDs could have their PCM layer read by conventional CD players, the top-of-the-shop dual-layer SACDs (with 8.5GB of storage, space for up to six discrete audio channels and DSD audio encoding) required a dedicated player.

A number of high-end Blu-ray players continue to offer SACD playback, but once the PlayStation 3 had its SACD compatibility deleted in 2007, the writing was almost as big as the wall on which it was written.

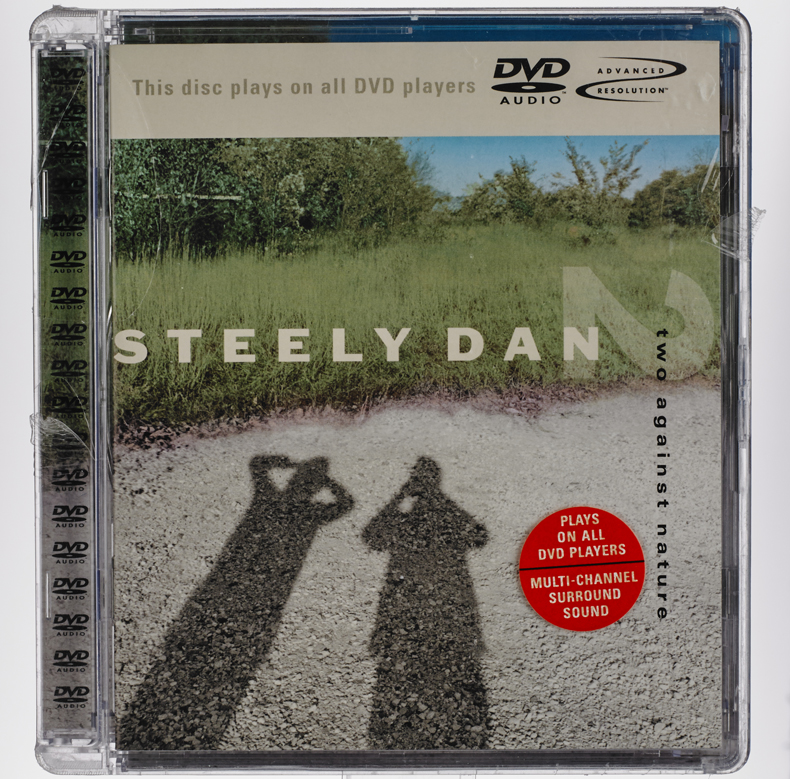

DVD-Audio

2000 - 2007

Like SACD, DVD-Audio sought to bring high-resolution audio to market in a format that was happily familiar and comfortable. And like SACD, to an extent it delivered the goods. Using DVD’s (relative to CD) colossal storage capacity meant music could be stored in any configuration from 1.0 mono to 5.1-surround sound. Mono or stereo information could be stored at 24-bit/192kHz, and even 5.1 stuff could enjoy 24-bit/96kHz resolution.

But despite backing from the likes of EMI, Universal and Warner Bros (or perhaps, in part, because of the restricted and rarefied DVD-A catalogues those record companies released), consumers were ambivalent towards DVD-Audio. Maybe the public were tired of the format set-to with SACD, or perhaps they were underwhelmed by the software available. Or maybe it was simply that they were unwilling to buy huge swathes of their music collections again.

Whatever the reason – and there was no arguing with the sonic benefits of the format – no brand has produced a dedicated DVD-A player since 2007.

HD DVD

2006 - 2008

The consumer electronics industry appears to relish a format war – and HD DVD is most recent example of its appetite for making the consumer the last stage of Research & Development. After the runaway success of DVD, High Definition Digital Versatile Disc was an obvious next step.

Developed jointly by Toshiba and NEC, it utilised existing DVD infrastructure and could store over three times as much information as DVD (15GB compared to 4.7GB). Its audio support – 24-bit/192kHz audio (for two channels) or 24-bit/96kHz (for up to eight) – was impressive too. But it was developed at the same time as Sony and its partners were working on the Blu-ray format – and Blu-ray could hold up to 50GB of information per disc.

Consumers were treated to another unedifying public scrap, but Sony’s decision to equip 2007’s PlayStation 3 with a Blu-ray drive, and the erosion of support from major film studios, meant this particular brawl was mercifully brief.

MORE:

Indulge in 6 of the best British hi-fi innovations and technologies

Bone up on QD-OLED TV: everything you need to know about the game-changing new TV tech

Love vinyl? Snap up (or challenge) our pick of 18 songs that sound their best on vinyl

Simon Lucas is a freelance technology journalist and consultant, with particular emphasis on the audio/video aspects of home entertainment. Before embracing the carefree life of the freelancer, he was editor of What Hi-Fi? – since then, he's written for titles such as GQ, Metro, The Guardian and Stuff, among many others.

-

I wonder whether 8K will be on there in the future too. :rolleyes: I am pretty sure that’s a tech too or maybe not? 🙃Reply

-

nopiano Oh, yes, and 3D telly. Actually, Betamax wasn’t a technical failure but a marketing one. Iirc JVC stole a march on the rental market with VHS so the weaker design became more popular.Reply -

Reply

Thanks mate. (y)nopiano said:Oh, yes, and 3D telly. Actually, Betamax wasn’t a technical failure but a marketing one. Iirc JVC stole a march on the rental market with VHS so the weaker design became more popular. -

Reply

I've still got a 3D telly and player plus active glasses :) I still find it rather fascinating when I play a 3D disk.nopiano said:Oh, yes, and 3D telly. Actually, Betamax wasn’t a technical failure but a marketing one. Iirc JVC stole a march on the rental market with VHS so the weaker design became more popular. -

nopiano Reply

3D was certainly fun at the cinema, and not following TV trends too closely I never really grasped why it petered out. I can only think there weren’t enough sources, or consumers couldn’t be bothered with the glasses.DougK said:I've still got a 3D telly and player plus active glasses :) I still find it rather fascinating when I play a 3D disk.

I think the LG telly we use now was 3D, as my step daughter bought it a few years ago. -

nopiano Now I’ve actually read the article, I think it’s worth noting that hybrid SACDs are still alive and well in the hands of a few classical labels, such as BIS.Reply -

Winter In my humble opinion 3d was a massive step forward any really enjoy the experience . Given most recent blu ray players still offer this surely tv s should do the same !Reply -

Roger_A I'm surprised there's no mention of Quadraphonics. With four competing systems each technologically different it's no surprise it never caught on.Reply -

Hifiman Not only have 3D televisions largely died but curved screens too. I never did understand their appeal and they seemed to mark a turning point for Samsung who could do no wrong until they went through a period of pushing them heavily.Reply -

jjbomber Apple Mackintosh TVReply

Apple III with it's 100% failure rate

Apple Mackintosh Performa x200

Apple Bandai Pippin games console

Apple USB Mouse (Hockey Puck)

Apple Mighty Mouse

Apple G4 Cube

Apple ipod shuffle 3

Apple Maps

Apple Quicktake 200 Digital Camera

Apple Newton

Apple Airpower

Apple itunes Ping

Apple MobileMe

Apple iphone4 antenna

Apple Airport Extreme